John, who always stood out in your waiting room due to his long-sleeved shirt, looked particularly tired today. You saw from the edge of his scalp line that his psoriasis flare was the reason for his attendance. He was embarrassed about his skin condition and struggled with day-to-day life because of it. He tried to avoid dark clothing as it made his shedding, scaly skin more apparent. The shedding skin also made his job as a kitchen helper challenging during food preparation.

WHAT IS PSORIASIS?

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease with predominant skin, nail and joint involvement. It has a bimodal age of onset (16–22 years and 57–60 years)(1) and affects both sexes equally.(2) Psoriasis is an immune-mediated disease with genetic predisposition. Risk factors and triggers include family history, physical (e.g. skin injury, illness, weather changes) and emotional stress, and alcohol intake.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

It is estimated that 2%–3% of the total global population has psoriasis.(3) In Singapore, it is estimated that at least 40,000 persons are affected with psoriasis.(4) Most patients with psoriasis can be managed in the primary care setting with topicals and regular monitoring. A holistic approach is crucial to assess disease severity and the impact on the patients’ life, such as on their mood, relationships and social stigma. Screening to look for the presence of joint involvement and comorbidities is useful to provide timely management and better disease outcomes.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

Establishing the diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually clinical and based on the presence of typical erythematous and scaly skin lesions, which may be pruritic. Psoriasis occurs in several distinct clinical forms.

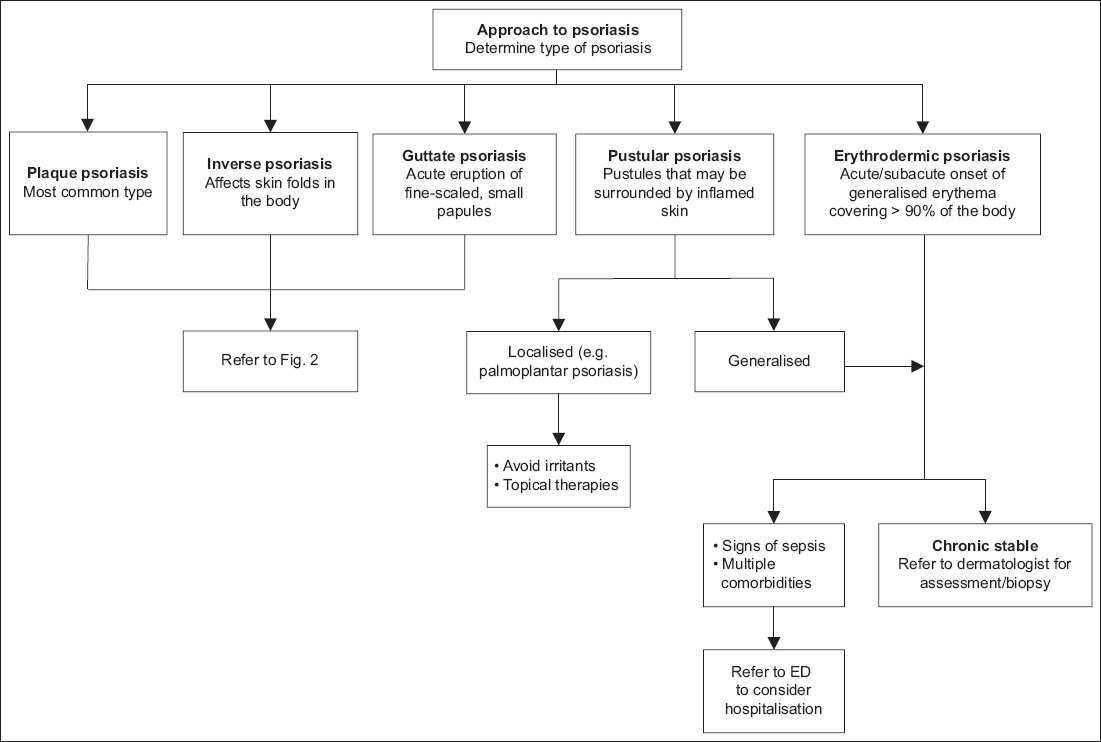

Fig. 1

Flowchart shows the approach to different clinical forms of psoriasis. ED: emergency department

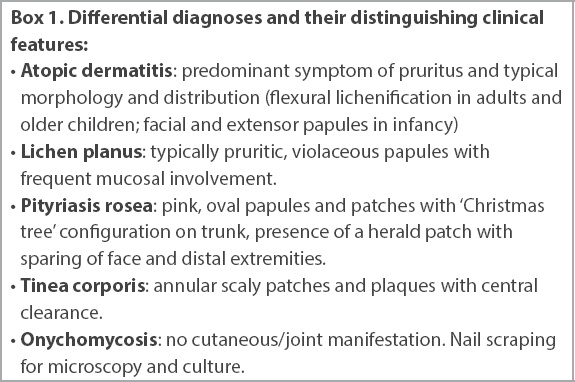

Box 1

Differential diagnoses and their distinguishing clinical features:

Psoriatic onychodystrophy

About 80% of patients with psoriasis are likely to develop nail psoriasis, or psoriatic onychodystrophy. Nail matrix involvement can result in features such as leuconychia, pitting, red spots in lunulae and crumbling. Nail bed involvement can cause onycholysis, salmon or oil-drop patches, subungual hyperkeratosis and splinter haemorrhages. Nail disease causes aesthetic and functional impairment, and is indicative of more severe forms of psoriasis as well as joint involvement.(8)

Psoriatic arthritis

Up to 40% of individuals with psoriasis will go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually within 5–10 years of cutaneous disease onset. Regular routine screening of patients with psoriasis is important for early detection of PsA. PsA is characterised by synovitis, enthesitis, dactylitis and spondylitis.(9)

Screen for other comorbidities

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of a variety of medical conditions such as depression, anxiety, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease.(10,11) Hence, it is important to screen patients for other comorbidities.

Management

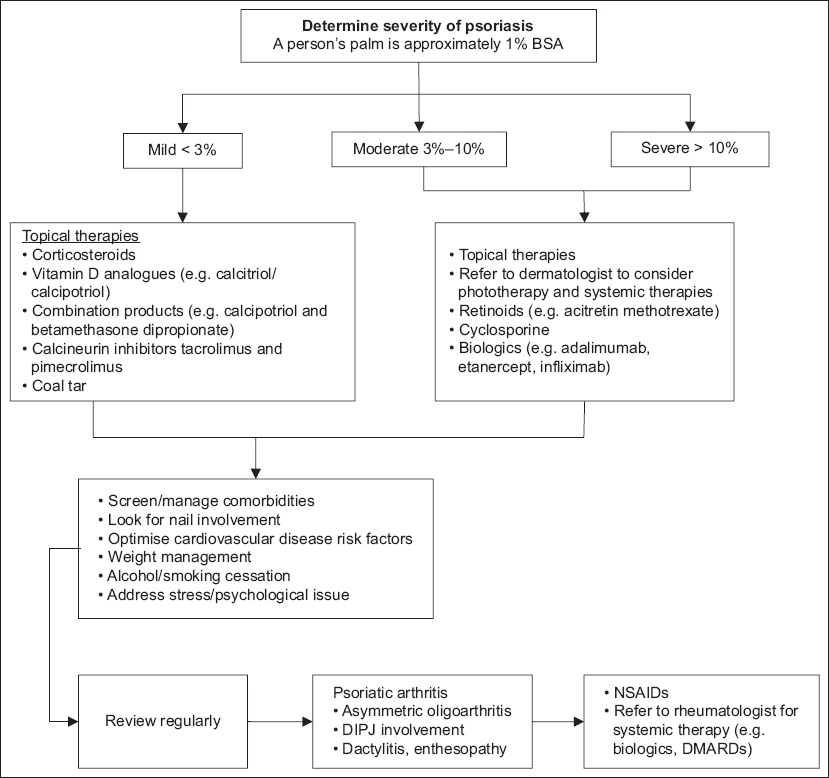

An individualised treatment plan is made after incorporating patients’ preferences, the disease’s impact on quality of life, and the potential benefits and adverse effects of therapies (

Fig. 2

Flowchart shows the approach to psoriasis of different severities.(12) BSA: body surface area; DIPJ: distal interphalangeal joint; DMARD: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Non-pharmacologic treatment

Non-pharmacologic management includes identification and avoidance of triggers, stress management, regular use of emollients, smoking and alcohol cessation, and weight management to reduce cardiovascular risk factors.

Pharmacologic treatment

Topical corticosteroids

Patients with mild to moderate disease can often be treated successfully with topical therapies. Use topical steroids of appropriate potency based on the location and severity of the skin lesions, such as the low-potency topical steroids 1% hydrocortisone or 0.025% betamethasone valerate cream on lesions on the face, genitals and flexures. More potent topical steroids can be used for thicker and more persistent lesions on the trunk and limbs.

Topical vitamin D3 analogues

Calcipotriol, a vitamin D3 analogue, is a first-line topical agent for treatment of plaque psoriasis and moderately severe scalp psoriasis.(6)

Combination products

For local, persistent lesions, potent topical steroids can be used in combination with a vitamin D analogue.

Systemic therapy

For moderate to severe psoriasis, phototherapy is a mainstay treatment, especially in cases that are unresponsive to topical agents.(6)

Systemic therapies such as acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine and biologics may be considered.

WHEN SHOULD I REFER TO A SPECIALIST?

If there are no contraindications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to relieve joint pain in patients with psoriatic arthritis while waiting for a rheumatologist review.

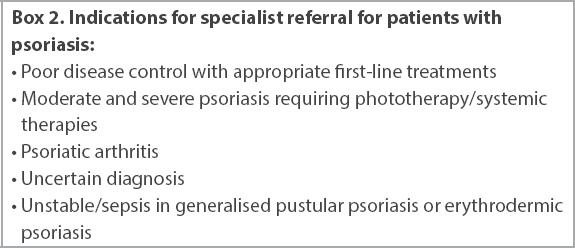

Box 2

Indications for specialist referral for patients with psoriasis:

USEFUL LINKS

About the Psoriasis Association of Singapore:

National Psoriasis Foundation, United States:

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects the skin and joints. It is also associated with multiple comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and mood problems.

-

Treatment for psoriasis should be individualised and tailored according to the severity of the psoriasis, comorbidities and treatment preferences.

-

Patients should be advised about weight management, reduction of alcohol intake and smoking cessation to reduce cardiovascular risk factors.

-

Patients who do not respond well to topical therapies should be referred to a specialist for early assessment.

-

It is important for physicians to recognise erythrodermic psoriasis and its complications and consider referring the patient to the emergency department if required.

You assessed John’s skin condition and noted that he had mild psoriasis with body surface area involvement of about 3%. Nail pitting was also noted. He did not have joint symptoms. You explained the diagnosis of psoriasis and that there are multiple effective treatments to control the disease. You reassured John that psoriasis is neither contagious nor infectious. He was given aqueous cream moisturiser, betamethasone valerate 1% scalp lotion and 0.1% betamethasone valerate cream for the lesions on his limbs. You encouraged him to speak to his co-workers to help them understand his situation. You also referred him to join the Psoriasis Association of Singapore’s support group.

SMJ-62-112.pdf