Abstract

We describe a case of recurrent uterine rupture at the site of a previous rupture. Our patient had a history of right interstitial pregnancy with spontaneous uterine fundal rupture at 18 weeks of pregnancy. During her subsequent pregnancy, she was monitored closely by a senior consultant obstetrician. The patient presented at 34 weeks with right hypochondriac pain. She was clinically stable and fetal monitoring showed no signs of fetal distress. Ultrasonography revealed protrusion of the intact amniotic membranes in the abdominal cavity at the uterine fundus. Uterine rupture is a rare but hazardous obstetric complication. High levels of caution should be exercised in patients with a history of prior uterine rupture, as they may present with atypical symptoms. Ultrasonography could provide valuable information in such cases where there is an elevated risk of uterine rupture at the previous rupture site.

INTRODUCTION

Uterine rupture is a rare but hazardous obstetric complication whose diagnosis can be hindered by atypical presentations. Much caution should be exercised in patients with a history of prior uterine rupture due to the elevated risk of recurrent rupture at the previous rupture site. In such cases, ultrasonography can provide valuable information.

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old woman (gravida 5, para 1) visited our obstetrics department for prenatal care under a senior consultant obstetrician at nine weeks of gestation. The patient’s obstetric history revealed a full-term, spontaneous and normal vaginal delivery in 2006, two subsequent terminated pregnancies in 2007 and 2008, as well as an interstitial ectopic pregnancy complicated by fundal rupture of the uterus at 18 weeks of gestation in 2011.

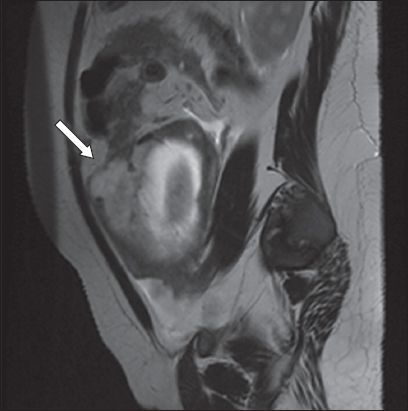

In 2011, the patient had an early booking scan at ten weeks’ gestation that suggested an intrauterine pregnancy. She was admitted at 18 weeks’ gestation for severe abdominal pain with a burning sensation in the upper abdomen. The patient was stable on admission and had no prior surgical history. Ultrasonography revealed a viable intrauterine pregnancy, with free intraperitoneal fluid. She subsequently developed tachycardia of 140 bpm. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed focal thinning and irregularity of the fundal myometrium, with a possible breach in the myometrium, and a placenta that appeared to be uncovered (

Fig. 1

MR image of the abdomen shows focal thinning and irregularity of the fundal myometrium. The placenta (arrow) appears to be uncovered due to a possible breach in the right anterolateral aspect of the myometrium.

The patient returned to our centre 13 months after her last pregnancy. Ultrasonography revealed an intrauterine pregnancy and screening showed no fetal anomaly. The couple was counselled that this was a high-risk pregnancy and the risk of a repeat rupture was highlighted in view of the patient’s obstetrics history. She was instructed to return at any signs of abdominal pain or other discomfort, and an elective Caesarean section was scheduled at 37 weeks of gestation.

At 34 weeks, the patient presented at our outpatient emergency department with the complaint of right hypochondriac pain of acute onset. She was clinically stable with blood pressure of 100/61 mmHg and heart rate of 82 bpm. On palpation, the abdomen was soft with no scar tenderness and the uterus was relaxed. There were no clinical signs of acute abdomen. Cardiotocography showed no signs of fetal compromise, but contractions once every 3–5 minutes were noted. Her cervix remained closed. Admission was advised to enable close monitoring in the labour ward and for further investigations.

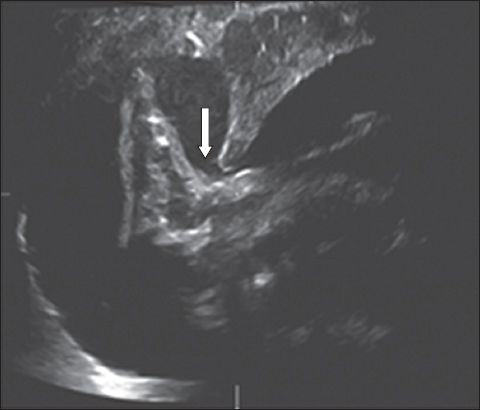

A preliminary blood test showed a haemoglobin level of 10.3 g/L. Following admission, the patient’s pain intensified and a repeat haemoglobin measurement was 8.8 g/L. Clinically, her vitals remained stable. An abdominal examination showed no palpable contraction despite contractions of once in two minutes on the tocogram. Fetal heart beat remained reassuring on continuous cardiotocography. In view of the patient’s history, worsening pain and drop in haemoglobin level, the couple was counselled on the possibility of a uterine rupture and an immediate Caesarean section was advised. However, they adamantly declined the Caesarean section and opted for ultrasonography. Immediate ultrasonography revealed a viable fetus in cephalic presentation. There was a discontinuity of the uterine wall at the right fundal region and the fetus’ foot was seen sticking out of the uterine fundus in an intact amniotic sac (

Fig. 2

US image shows discontinuity of the uterine wall at the right fundal region (arrow) and the fetus’ foot sticking out of the uterine fundus in an intact amniotic sac.

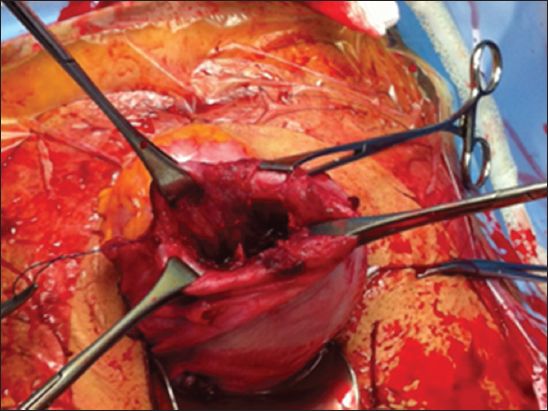

The couple were counselled and consented to an emergency laparotomy. A rupture in the right uterine fundus was noted, with intact membranes bulging through it. The fetus, which was delivered via a lower uterine incision, was male and weighed 1,990 g, with APGAR scores of 9 at both one and five minutes. There was no haemoperitoneum. After the placenta was removed, inspection of the uterus fundus revealed a 5 cm × 5 cm rupture (

Fig. 3

Photograph shows rupture of the uterine fundus.

DISCUSSION

Uterine rupture is a rare but important obstetric complication in view of its associated maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. The incidence of uterine rupture is estimated to be one in 6,331 deliveries at our centre, the largest obstetric hospital in Singapore.(1) Clinical presentation of uterine rupture cases can be extremely variable. In a review of uterine rupture cases conducted at our centre, the commonest presentations among patients with scarred uteri were found to be abnormal cardiotocogram findings with variable or late decelerations, blood-stained liquor, acute abdomen and shock.(1)

Our patient had none of the above clinical features. Instead, she was clinically stable and presented with right hypochondriac pain. In such cases, a high level of suspicion for uterine rupture should be maintained in light of the patient’s past history. For patients with scarred uteri, atypical presentations with absence of fetal distress could be decoys from the true diagnosis and a high level of vigilance is imperative. Failure to exclude the important differential diagnosis of uterine rupture could potentially lead to the catastrophic outcomes of poor maternal as well as fetal morbidity and mortality.

Ultrasonography can be a useful tool for the timely detection of uterine rupture in stable patients who have atypical presentations suspicious of uterine rupture. Bedside ultrasonography can allow for a rapid preliminary survey of uterine wall integrity, which could aid decision-making on the need for immediate surgical intervention. A secondary assessment of fetal wellbeing could also be done.

The possibility of atypical presentations should be conveyed to these high-risk patients to facilitate early assessment and intervention. Having postnatal discussions with uterine rupture patients about subsequent fertility is also a good practice, in view of its possible recurrence. Contraception advice is necessary and it must be adequately conveyed to the couple that shorter interpregnancy intervals may increase the risk of rupture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the patient to whom the above report relates for giving her written consent to the publication of the case, including the use of photographic illustration.