Abstract

A doctor’s attire is important in making a positive first impression and enhancing the overall healthcare experience for patients. We conducted a study to examine the perceptions and preferences of patients and doctors regarding six types of dress codes used by doctors in different scenarios and locations. A total of 87 patients and 46 doctors participated in the study. Separate sets of questionnaires containing four demographic questions and 14 survey questions were distributed to the two groups. Most patients preferred doctors to dress formally in white coats regardless of the scenario or location, whereas the majority of doctors preferred formal attire without white coats. Both groups preferred operating theatre attire in the emergency department. Our findings confirmed that patients perceived doctors in white coats to be more trustworthy, responsible, authoritative, confident, knowledgeable and caring. There is a need to educate the public about the reasons for changes in doctors’ traditional dress codes.

INTRODUCTION

A doctor’s attire is influential in not only making a positive first impression but also enhancing the overall healthcare experience for patients. In 2001, two Australian studies by Harnett(1) and Gooden et al(2) suggested that 36%–59% of patients preferred junior doctors to wear white coats for easier identification and hygiene purpose, and as a symbol of professionalism. Conversely, other studies(3,4) suggested that, from a patient’s perspective, the doctor’s attire does not correlate with the clinician’s courteousness, concern or professionalism. We conducted a questionnaire study in an attempt to understand the perceptions and preferences of patients and doctors regarding the different types of dress codes that doctors choose for various clinical scenarios in different locations.

METHODS & RESULTS

A total of 87 (46.0% female, 54.0% male) patients and 46 (28.0% female, 72.0% male) doctors participated in the survey. The patients were recruited from the inpatient wards, outpatient department, and accident and emergency department of University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, while the doctors were from the hospital’s surgical, orthopaedics, and accident and emergency departments. The ages of the 87 patients were as follows: ≤ 20 years (n = 3); 21–30 years (n = 15); 31–40 years (n = 20); 41–50 years (n = 8); 51–60 years (n = 17); 61–70 years (n = 13); and ≥ 71 years (n = 11). Among the 46 doctors, 31.0% were ≤ 30 years, 67.0% were 31–40 years and 2.0% were 41–50 years.

Separate sets of questionnaires, which included four demographic questions and 14 survey questions, were distributed to the patient and doctor groups. All the participants were asked to rate their most preferred attire based on the attached pictures of different attire usually worn by male and female doctors. Patients were then asked to select their preferred choice of doctor’s attire, while the doctors selected their personal preference of dress code for ten different scenarios that are usually encountered in clinical practice, in three different locations.

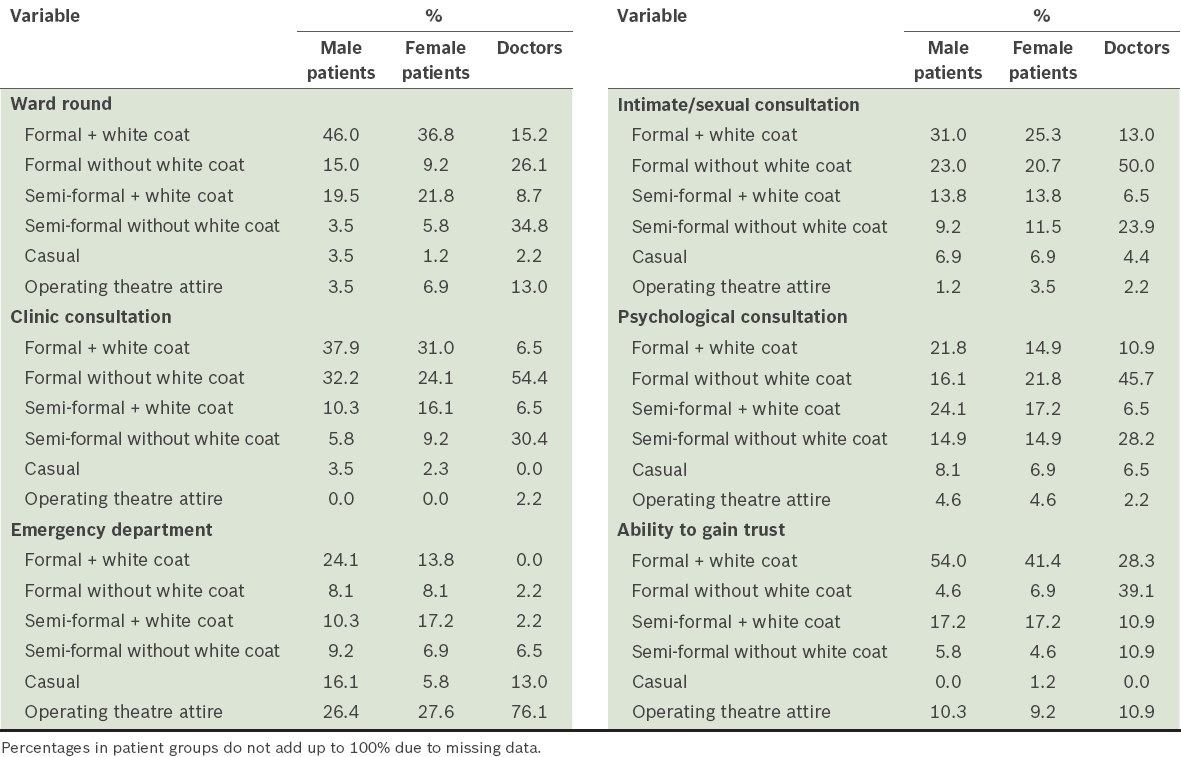

Our results revealed that both male and female patients preferred doctors to dress formally in white coats during ward rounds (46.0% male, 36.8% female), clinic consultations (37.9% male, 31.0% female) and intimate/sexual consultations (31.0% male, 25.3% female) (

Table I

Preferences of patients and doctors regarding a doctor’s attire in different scenarios and locations.

Among doctors, 54.4%, 50.0% and 45.7% preferred formal attire without a white coat for clinic consultations, intimate/sexual consultations and psychological consultations, respectively. Not surprisingly, the majority of doctors (39.1%) perceived that dressing in formal attire without a white coat would be most likely to help them gain a patient’s trust. However, contrary to patients’ preference for formal attire with a white coat during ward rounds (46.0% male, 36.8% female), the majority of doctors (34.8%) preferred semi-formal attire without a white coat in this setting. During psychological consultations, male patients (24.1%) preferred semi-formal attire with a white coat as compared to female patients (21.8%) and doctors (45.7%), who preferred formal attire without a white coat. In the emergency department, the majority of patients (26.4% male, 27.6% female) and doctors (76.1%) consistently preferred doctors to dress in operating theatre attire.

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such study on preferences for doctors’ dress codes from both the patient’s and doctor’s perspectives in the Malaysian community. Our study found that there are differences in preferences for doctors’ dress codes between patients and doctors. These findings highlight the need to educate the public about the reasons behind changes in doctors’ traditional dress codes. Bridging the understanding between doctors and patients with respect to the doctor’s dress codes in different scenarios and locations can lead to a more positive doctor-patient relationship. Ultimately, this will enhance the delivery of healthcare and the overall healthcare experience of patients.