Abstract

Frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome wherein the individual has low reserves and is highly vulnerable to internal and external stressors. Although it is associated with disability and multiple comorbidities, it can also be present in individuals who seem healthy. Frailty is multidimensional and its pathophysiology is complex. Early identification and intervention can potentially decrease or reverse frailty, especially in the early stages. Primary care physicians, community nurses and community social networks have important roles in the identification of pre-frail and frail elderly through the use of simple frailty screening tools and rapid geriatric assessments. Appropriate interventions that can be initiated in a primary care setting include a targeted medical review for reversible medical causes of frailty, medication appropriateness, nutritional advice and exercise prescription. With ongoing training and education, the multidisciplinary engagement and coordination of care of the elderly in the community can help to build resilience and combat frailty in our rapidly ageing society.

Annie Lim, who had Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, visited you at your clinic one day. A cheerful 78-year-old, she was single, lived alone and had attended her follow-up with you regularly for the past ten years. She did her chores herself and was a familiar face in the neighbourhood. For the past six months, Annie had been feeling tired and, for the first time, revealed her difficulty walking to the nearby coffeeshop. Her walking speed was noticeably slower and she had been visiting the coffeeshop less often. She had bought a walking stick three months ago on your advice and was using it to help her get around. Annie told you that this was part of normal ageing and asked for a pill to strengthen her legs.

WHAT IS FRAILTY?

Frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome wherein the individual has low reserves and is highly vulnerable to both internal and external stressors. Frailty encompasses physical frailty,(1) which is the most widely studied and most easily recognised state. Frailty is also conceptualised as the accumulation of deficits,(2) including physiologic changes that occur with ageing, physical and cognitive diseases, as well as socioeconomic factors. The pathophysiology of frailty is a complex interaction of diseases and age-related decline that leads to a general state of low functional reserve capacities, affecting multiple domains. Frailty is often described as a transitional phase between successful ageing and disability. Progression of frailty leads to increased risk of falls, disability, immobility, hospitalisations, institutionalisation, caregiver burden, decreased quality of life and even death.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

The disability and disease burden of our society is increasing with the rapidly ageing population in Singapore. Patients usually seek healthcare attention only when they experience symptoms or when crises emerge. Care of patients is mostly disease-centred and episodic, with high emergency attendance and hospital bed occupancies that threaten the sustainability of our healthcare resources.

The limitations of our current care model is that the frail elderly often present to the healthcare system, especially tertiary care, when they are in the more severe stages of frailty. At this stage, the appropriate interventions, although useful, might have limited benefit to reverse the frailty state. In the community, the majority of the elderly aged 65 years and older may appear healthy and independent, even though they could already be in the pre-frail and mildly frail stages and exhibiting the physical frailty phenotype of weakness, slowing down, being tired, having less physical activity and loss of weight.(1) Unfortunately, these symptoms of frailty are commonly attributed to normal ageing, without the recognition that they are potentially reversible and preventable.(3-8) The recently published Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines summarised the evidence on how frailty can be clinically assessed, diagnosed and treated with non-pharmacological therapies.(9) The World Health Organization has also recently published the Integrated Care for Older People guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity.(10)

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

A recent systematic review of data from 21 studies and more than 61,500 community-dwelling elders has shown that the worldwide prevalence of pre-frailty and frailty ranges from 34.6% to 50.9% and 5.8% to 27.3%, respectively.(11) There is also evidence that as age increases, the prevalence of frailty also increases. A local prevalence study of 1,051 older adults showed that the prevalence of pre-frailty and frailty was 37% and 6.2%, respectively.(12) In this article, we aimed to discuss physical frailty, and the approach to and management of frailty in the primary care setting.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

There is no gold standard screening test for frailty, and multiple tools have been developed for different settings and populations.(13) Increasing evidence shows that frailty is potentially reversible with early screening and intervention. All healthcare providers and patients, as well as the general public, need to be aware that frailty is a distinct and recognisable syndrome that is independent of disease and disability, and is potentially reversible with interventions. Primary care doctors and community nurses have opportunities to meet individuals who are in pre-frail and mild frail states when they attend health screenings or reviews for acute or chronic illnesses. Healthcare providers can also educate their patients, friends and families about this condition so that they can encourage vulnerable older adults to get screenings, early interventions and access to other appropriate resources.

As frailty is a complex and multi-dimensional syndrome, effective interventions require multi-domain and multidisciplinary approaches. The literature suggests that an early comprehensive geriatric assessment with appropriate interventions is effective for improving function and survival for the elderly. However this is time-consuming and challenging to perform in any busy primary care practice. Hence, shorter geriatric screening tools have been developed.

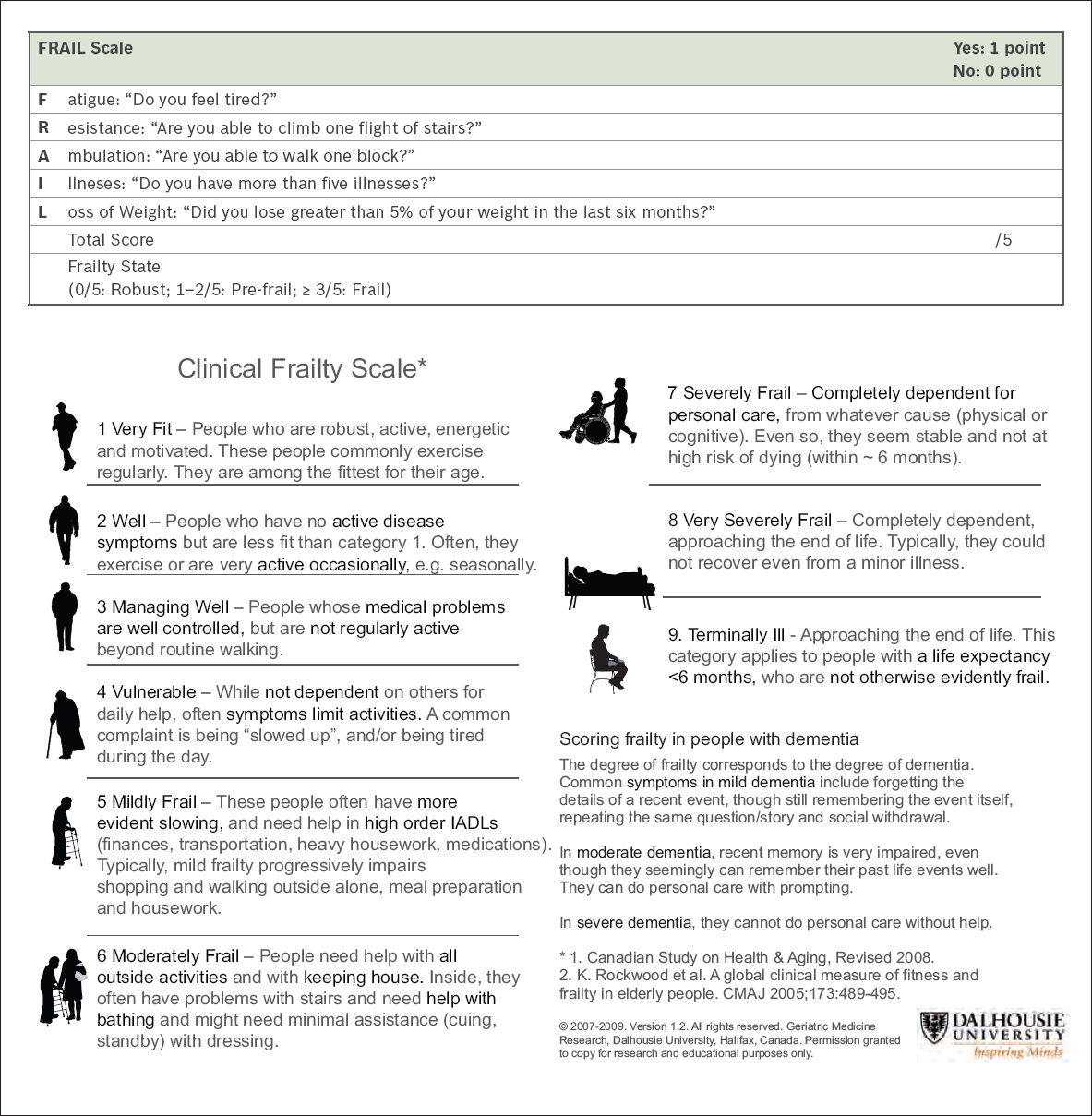

To identify frailty in the community and primary care setting, we recommend performing an initial screening using the FRAIL (

Once a patient is screened to be pre-frail or frail, a targeted medical review at the primary care clinic can be carried out.(17) The important objectives of this review are to: (a) Identify patients who may have malnutrition through a simple calculation of their body mass index (BMI). The target for elderly persons should be 22–26 kg/m2. (b) Evaluate any possible underlying medical causes of frailty, e.g. hypothyroidism, anaemia, cognitive impairment, depression as a cause of fatigue, weakness and weight loss (with history, physical examination and measurements of full blood count, renal panel, thyroid panel and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels). (c) Identify any red flags for more sinister diseases requiring specialist referral, especially problems of unintentional weight loss or any swallowing problems. (d) Perform a medication review to ensure medication appropriateness and reduce polypharmacy. (e) Ensure that chronic disease control is optimised.

Interventions that can be easily initiated at the point of primary health contact are: (a) Improve protein or caloric intake, especially in those who are malnourished or experiencing weight loss, with appropriate nutritional advice.(9,18) (b) Replace vitamin D if there is vitamin D deficiency.(9,19,20) (c) Prescribe exercise,(21) including exercises with a resistance-training component,(9) and provide information on exercises available in the community,(22,23) including growing community and social initiatives for the elderly such as the ActiveSG Masters Club,(22) HAPPY (Healthy Ageing Promotion Programme for You) programme,(24) Share-A-Pot(25) and Gym Tonic programmes(26) in senior activity centres and other community venues. (d) Provide referrals to day rehabilitation centres for those who may benefit from a more intensive programme and need further assessments and interventions by physiotherapists, especially if they have faced recent, significant functional decline.

WHEN SHOULD I REFER TO A SPECIALIST?

Geriatric patients may be referred to a geriatrician or the appropriate specialist or allied health professional when they have the following (the list is not exhaustive): (a) possible medical conditions that warrant further assessment, e.g. anaemia requiring further work-up or weight loss with red flags; (b) possible cognitive impairment or depression that needs specialist review and management; (c) falls or acute, significant functional decline that requires a more comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary management in the tertiary healthcare setting; (d) poor social support that can be referred to a community case manager; and (e) a more gradual decline in function that may benefit from a physiotherapist review or a more intensive programme at a day rehabilitation centre.

The role of community nurses

Community nursing is not new in Singapore, but the growing healthcare challenges in our future have expanded the demand for community nurses and their work scope.(27,28) They now form the frontline healthcare teams in our community, working alongside primary care clinics in the care of frail older adults. Their work involves prevention of frailty, early identification and linking to primary care, case management and care coordination.

Prevention of frailty

Education and health coaching are an important function of community nurses. Community health posts operate within the community to offer education on health monitoring (e.g. weight, BMI, blood pressure) and advice on diet, lifestyle and exercise to individuals, with the aim of promoting health and wellness.

Early identification and linking to primary care

Other community-based programmes screen for vulnerable individuals with geriatric assessment tools before a crisis occurs. These include screening for other geriatric syndromes such as falls and cognitive impairment, as well as performing more detailed assessments of the seniors’ drug history, functional and psychosocial challenges. Nurses in these programmes refer any identified individuals to their primary care providers for further assessment and follow-up care, and involve appropriate care partners such as allied health professionals and/or specialists.

Case management and care coordination

Management of frailty involves collaboration with various care providers from the health and social sectors. Good management of frail older adults in the community involves coordination and continuity of care. Currently, community nurses support community nursing posts and some senior activity centres, and also provide some support via the primary care networks. Community nurses can direct or assist in this coordination and bridging between health and social care, focusing on a person-centred approach and more effective use of resources.(29) Case management entails active case finding, assessments, coordination and monitoring of patients’ progress. Activities may include case discussions and conferences with relevant care providers or disciplines in the management of patients with complex needs.

CONCLUSION

Frailty is recognised as an emerging geriatric giant and poses wide-reaching consequences for the individual, family and the society in the future. Healthcare paradigms are changing to tackle frailty in its early stages, delay its progression to disability and provide a system that supports ageing in place for the elderly.

Close partnerships between community nurses and primary care physicians are essential to support the complex health and social needs of frail older adults in the community. Currently, community volunteers are undergoing training to screen for frailty in the community-dwelling elderly, and community nurses are also performing targeted and rapid geriatric and frailty assessments at community health posts. As this is an emerging programme, different opportunities are found in each regional health system. Such programmes are likely to be part of our frailty-ready health system of the future, in which community nurses will be available to support primary care physicians and patients when the need arises.

Currently, finding an exercise programme that is intensive and effective enough to target frailty in the elderly is challenging, although there are already some programmes in place.(22-26) There are ongoing efforts to engage with the Health Promotion Board, ActiveSG and other community partners to improve such programmes, as well as train and equip the exercise trainers.

A multidimensional approach that goes beyond physical frailty and acknowledges cognitive and psychosocial elements is important to produce significant and sustained improvement. The success of frailty management in the community pivots on building partnerships among healthcare workers, allied health staff (including social workers and case managers, dieticians, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists and exercise trainers) and the wider social community network. Together with the engagement of the patient and family, elderly individuals can be empowered to live independently within their individual environments. This would enable the senior and society as a whole to build resilience and thereby combat frailty.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Frailty is a distinct syndrome in the elderly that is under-recognised but can be reversed with interventions, especially in the pre-frail and mildly frail stages.

-

Many pre-frail and mildly frail seniors’ first point of contact with the healthcare system is with the primary care physician. Hence, the opportunity should be taken to identify them in the primary care setting.

-

Quick and easy ways to screen for frailty in the primary care setting include the FRAIL scale and Clinical Frailty Scale, which do not require any equipment or complicated measurements.

-

A targeted medical review is recommended to identify potentially treatable medical conditions that may contribute to frailty, and patients can be referred to the specialist setting where appropriate.

-

Primary care physicians can start interventions for frailty in the community by providing appropriate nutritional advice and improving patients’ exercise participation.

-

As part of delivering quality patient-centred care, primary care physicians should involve patients and their families in individualising treatment modalities, preferences and options.

After three months, Annie returned for her review. You noted that her walking speed had improved. Her visits to the physiotherapist in a day rehabilitation centre had been very effective. She had also heeded your advice to increase her protein intake on top of her diabetic diet. Annie also received support from a community case manager whom you had referred her to. She thanked you for your help in screening her early so that her condition could be improved in time.

SMJ-59-245.pdf

APPENDIX