Jane, a 42-year-old homemaker, presented with a persistent sensation of throat discomfort and fear of choking during eating over the past six months. She had sought multiple consultations with several primary care physicians and had undergone extensive ‘full-body check-ups’ – including laboratory investigations, cancer markers, radiography, nasoendoscopy and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. The results were all unremarkable except for laryngopharyngeal reflux. She experienced some improvement in the globus sensation after she was started on proton-pump inhibitors but continued to have significant difficulty with eating. Jane said that she now required three hours to complete each meal and was only able to tolerate minced food or porridge. She had lost 8 kg since the onset of her symptoms. She was distressed and reported worsening anxiety and constant ruminations about her symptoms. She also experienced anhedonia and insomnia.

WHAT IS SOMATISATION AND ABNORMAL ILLNESS BEHAVIOUR?

Patients with multiple and persistent physical symptoms are commonly encountered in primary care and other medical settings.(1) Physicians have long observed that physical symptoms can have emotional origins. Somatisation is the term used to describe abnormal illness behaviour in which patients experience and seek medical attention for physical symptoms when they actually have underlying psychological distress.(2) It is an idiom of distress through which patients with psychosocial problems communicate their suffering through physical symptoms. Suffering extends beyond the experience of bodily symptoms, also encompassing emotional and behavioural aspects such as excessive health anxiety and checking behaviour.

Somatic symptom and related disorders

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, what was previously known as ‘somatisation or somatoform disorders’ has been replaced by ‘somatic symptom and related disorders’. This new category includes somatic symptom disorder (SSD), illness anxiety disorder, conversion disorder (functional neurological symptom disorder), psychological factors affecting other medical conditions, factitious disorder, other specified somatic symptom and related disorder, and unspecified somatic symptom and related disorder. The common feature of all these disorders is the presence of prominent somatic symptoms associated with significant distress and impairment.(3)

The previous diagnostic criteria for somatisation disorders were problematic. First, medically unexplained symptoms were a central feature even though it is impracticable to exclude all organic disorders completely. Second, the patient’s experience and interpretation of symptoms, which also contributes significantly to morbidity, were inadequately accounted for.

Abnormal illness behaviour was conceptualised by Pilowsky as “the persistence of a maladaptive mode of experiencing, perceiving, evaluating and responding to one’s health status, even though a doctor has provided a lucid and accurate appraisal of the situation and management to be followed (if any), with opportunities for discussion, negotiation, clarification based on an adequate assessment of all biological, psychological, social and cultural factors”.(4) Patients with somatic symptom and related disorders often manifest abnormal illness behaviour; they typically present to physicians repeatedly with complaints of various somatic symptoms, make frequent requests for investigations and referrals to specialists, or have intractable symptoms that fail to respond to multiple treatments.

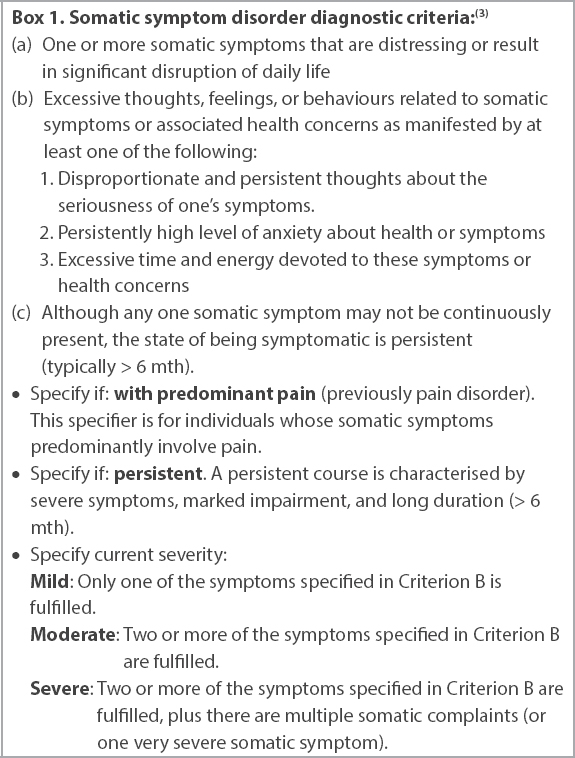

Somatic symptom disorder

For SSD, the emphasis is diagnosis based on the presence of positive symptoms and signs. Patients typically have multiple distressing somatic symptoms that disrupt their daily lives. They also have high levels of worry about illness and preoccupation with their symptoms.(3) Notably, a diagnosis of SSD does not require that the somatic symptoms be medically unexplained (

Box 1

Somatic symptom disorder diagnostic criteria:(3)

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

The prevalence of SSD and related disorders is estimated to be 5%–7% in the general population.(3) Up to 80% of primary care visits for evaluation of common symptoms such as giddiness, chest pain and headache do not identify any organic cause.(1) The absence of an organic cause does not necessarily point to a psychiatric aetiology. Nonetheless, an estimated 20%–25% of patients who present with acute somatic symptoms go on to develop a chronic somatic illness.(5) Persistence and deterioration in function are most likely in patients with more physical complaints and greater psychiatric comorbidity.(6)

Patients with multiple somatic complaints often receive extensive investigations for physical illnesses and unnecessary treatments, whereas psychological factors are insufficiently explored.(7) This may result in iatrogenic medical problems, which paradoxically reinforces their abnormal illness behaviour.(7)

Furthermore, patients with SSD utilise an inordinate amount of healthcare resources. One study estimated that patients with medically unexplained symptoms generate nine times the healthcare cost of an average patient.(8) Early detection may allow abnormal illness beliefs and behaviours to be modified before they become chronic and resistant.

Physicians often get frustrated by patients’ frequent complaints and dissatisfaction with treatment. They may perceive that their attempts to help such patients are ineffective and experience them as ‘difficult’. Conversely, patients may feel invalidated and feel accused of fabricating symptoms. This jeopardises the collaborative physician-patient relationship and worsens the cycle of illness.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

When evaluating patients with multiple somatic symptoms or abnormal illness behaviour, it is important to keep an open mind and to adopt a holistic, non-judgemental approach.

Recognise patients with possible abnormal illness behaviour

Several features in a patient’s clinical presentation may invite suspicion of abnormal illness behaviour, including: (a) the presence of multiple symptoms that seem to lack an adequate explanation; (b) complaints that persist despite interventions that usually help most others; (c) excessive concern with bodily appearance or certain aspects of health; (d) chronic or excessive pain; and (e) a history of extensive diagnostic testing or ‘doctor hopping’.

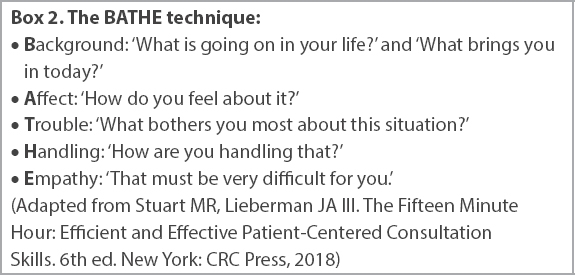

Foster a sound therapeutic alliance with the patient

Empathy is central to fostering a strong therapeutic relationship with the patient. Primary care physicians should listen actively and validate distress. Gently encourage the patient to tell you more about their problem by asking questions (e.g. ‘How has it been like for you?’) and making statements (e.g. ‘I can see it has been very distressing for you’). Explore the meaning of the symptoms to the patient, clarifying and communicating understanding. The BATHE technique is a helpful approach to effectively understand a patient’s problems, their impact and his or her coping strategies (

Box 2

The BATHE technique:

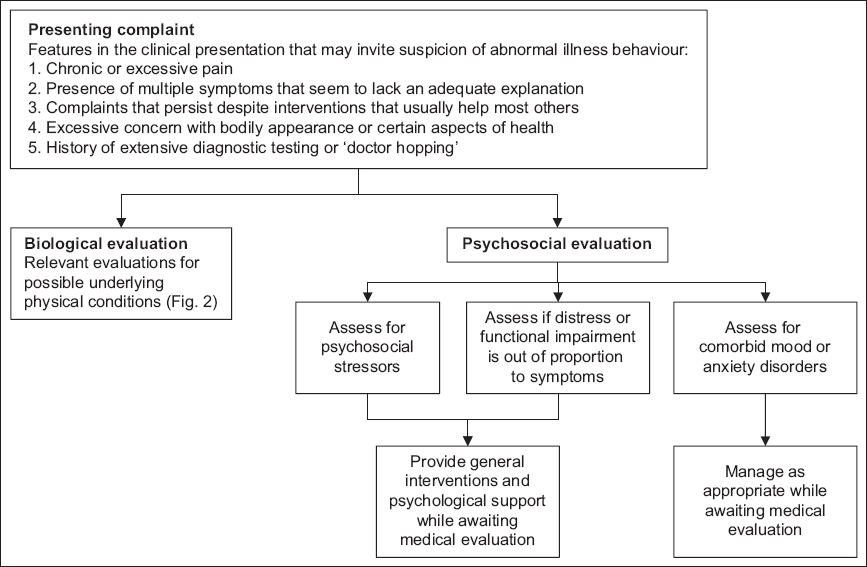

Use a biopsychosocial history-taking approach

We recommend concurrently evaluating physical conditions and exploring associated psychosocial stressors (Figs.

Fig. 1

Flowchart shows the biopsychosocial history-taking approach. This is an integrated process that should not be staged or compartmentalised.

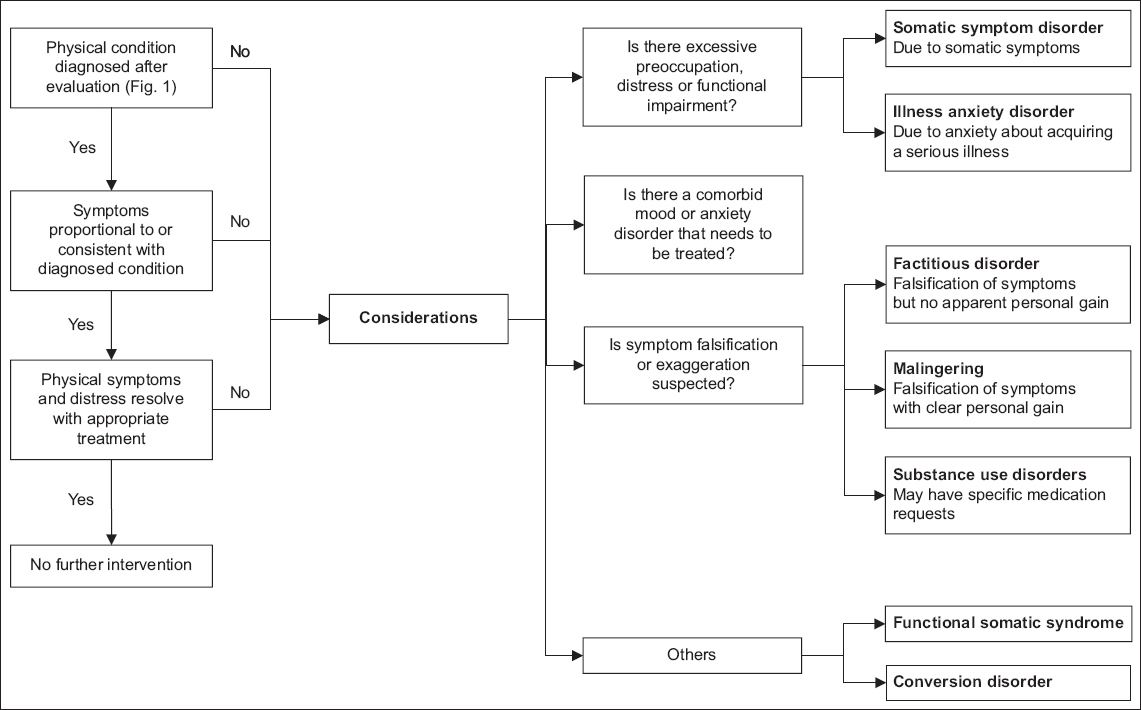

Fig. 2

Flowchart shows the process of differentiating somatic symptom disorder from its other related disorders. Note that somatic symptom and related disorders are not mutually exclusive from, and can be comorbid with, mood and anxiety disorders.

Psychosocial stressors, such as the recent passing of a loved one from a serious illness, may exacerbate the degree of anxiety that patients experience towards their somatic symptoms. Patients may also have a degree of psychological distress or functional impairment that is disproportionate to the severity of their somatic symptoms. It is important to identify this, as primary care physicians are well-placed to provide general interventions and offer psychological support while awaiting the results of physical investigations.

Exclude depressive and anxiety disorders

In primary care settings, more than 70% of patients with major depression present with predominantly somatic complaints rather than affective symptoms of depression.(9) Many depressed patients only acknowledge psychological symptoms when asked. Adjustment disorder and grief reactions may present similarly. Exploring recent significant life changes or losses and screening for features of pervasive mood symptoms (i.e. loss of interest, sense of worthlessness and guilt) may point towards stress-related or depressive illnesses.

Anxiety disorders encompass both psychological and physical symptoms associated with hyperarousal. Unsurprisingly, they frequently co-occur with functional somatic symptoms. Anxious patients may have distorted cognitive appraisal that causes them to experience benign physical symptoms as alarming. Anxiety can also significantly lower their pain threshold.(10) Difficulty in controlling worry, recurrent panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive features or a traumatic antecedent may suggest disorders of anxiety.

If the patient fulfils the criteria for depression, adjustment disorder or an anxiety disorder, the diagnosis should be made accordingly. However, SSD and its related disorders should be considered early in patients with multiple somatic complaints or abnormal illness behaviour. As with any other psychiatric condition, and given the high comorbidity, suicide risk should be assessed.

Differentiate somatic symptom disorder from other related disorders

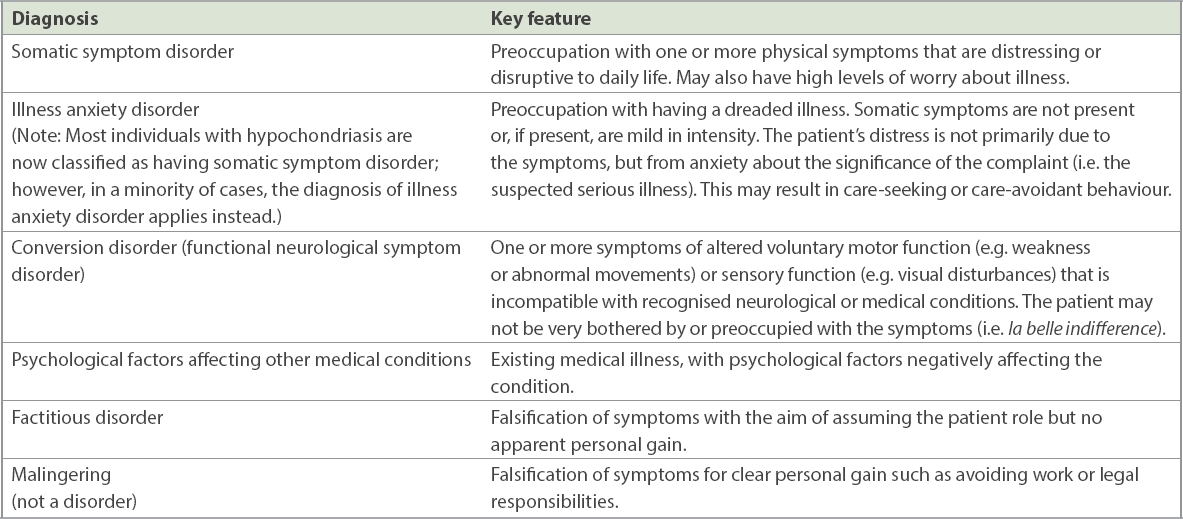

Individuals with SSD tend to be preoccupied with one or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption in their daily lives. This is usually accompanied by significant worry about their health. Key clinical features differentiating SSD from other related disorders are summarised in

Table I

Key features differentiating somatic symptom disorder from other related disorders.

Notably, SSD and its related disorders may coexist with other physical or mental disorders. It should be emphasised that diagnosis of SSD or other related disorders should not be an end in itself but a means to alleviate the patient’s distress. When appropriately made, the diagnosis of SSD enriches the diagnostic formulation and should guide a holistic treatment approach.

Recognise functional somatic syndromes

Numerous medical syndromes in the literature are characterised by subjective medical complaints and associated with a moderate to high degree of personal distress, but lack hallmark clinical findings. These include chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia and a range of environmental intolerance. Consideration of these syndromes invites more focused syndrome-specific interventions, including dietary, lifestyle and other physical interventions.

Be mindful of medication misuse and comorbid substance/alcohol use disorders

Patients with somatic symptom or related disorders are frequently prescribed medications with potential for dependence such as opioid-containing drugs and sedatives.(5) Features suggestive of abuse include requesting for specific medications, bargaining, presence of drug-related forensic history, prior history of substance dependence and comorbid alcohol use disorder.

Order physical investigations and refer to specialists as routinely indicated

Appropriate diagnostic investigations should be selected based on history and physical examination. Refer patients to specialists only when there is a clinical suspicion of a condition that warrants specialist evaluation and treatment, and not simply to allay their anxiety or out of frustration. A meta-analysis by Rolfe and Burton found that physicians overestimate the value of diagnostic testing in reassuring patients. Tests for symptoms with low risk of serious illness did not decrease illness anxiety or alleviate symptoms.(11) Watchful waiting is generally acceptable for most patients with unexplained complaints but is contingent on good communication between the physician and patient.(12)

HOW SHOULD I MANAGE PATIENTS WITH MULTIPLE SOMATIC SYMPTOMS?

For patients with multiple somatic symptoms, any diagnosed physical or psychiatric conditions should be treated concurrently according to relevant guidelines. Medical evaluation may uncover conditions such as fibromyalgia that are chronic and difficult to treat. Even with the best treatment efforts, some patients may remain persistently distressed by their somatic symptoms and have excessive thoughts, feelings and behaviours related to the symptoms. There is preliminary evidence that antidepressants may be beneficial, although it is unclear if this is a general benefit mediated through reduced depression and anxiety.(13) While symptomatic medications offer relief in some patients, it is important to consider risk-benefit ratio and minimise polypharmacy. The following helpful management principles are summarised from available literature.(7)

Educate patients on the connection between psychosocial stressors and symptoms

Somatic symptoms and psychological distress have a bidirectional link and can perpetuate each other. Moving away from investigating somatic symptoms (which may amplify and perpetuate symptoms) to exploring psychosocial problems could steer the consultation away from a relentless but futile search for an elusive illness. Normalise the co-occurrence of physical and psychological symptoms and draw analogies to explain how stress and physical symptoms interact, such as getting headaches when stressed or ‘butterflies in the stomach’ when anxious, examples that many patients can relate to.

Avoid creating a dichotomy between physical and psychological causation of symptoms. Comments such as ‘Your symptoms are all in the mind’ or ‘There’s nothing wrong with you medically’ are not helpful and may make the patient more defensive. Instead, helping the patient understand the mind-body interaction and how they can cope with their symptoms can instil hope and a sense of self-efficacy.

Communicate empathically

When communicating with the patient, empathy is important. Summarise medical findings and reassure the patient that serious medical conditions are unlikely. Statements should be validating and comforting, such as, ‘Your discomfort is real and distressing to you, but fortunately, you are not suffering from a serious illness’. Regular appointments should be scheduled at short intervals to reassure patients that they will continue to be monitored, but they should be discouraged from making multiple ad-hoc visits for emergent symptoms in between appointments.

Collaborate with patient and colleagues to establish shared treatment and follow-up plans

Engage patients when coming up with treatment goals, such as identifying and managing contributing psychosocial factors, improving function and deciding among treatment options. Discuss with patients the considerations for physical investigations and specialist referrals, and the likely outcomes of each. Patients should be gradually steered towards the goal of improving function and away from a fixation with discovering and curing an elusive or mysterious illness. If the patient is referred to a specialist, it is also helpful to communicate with the specialist to develop shared treatment plans and goals.

Enhance social support

Bolster social support for the patient by liaising with the family or engaging community support options. Addressing ongoing psychosocial stressors in practical ways may help to alleviate distress.

Consider referral for psychotherapy

Psychotherapy may benefit patients who are receptive to therapies that address the mind-body connection. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapies (MBT) have proven benefit for somatisation.(14,15) CBT aims to identify and reduce automatic, dysfunctional thoughts that perpetuate or worsen somatic symptoms. MBT facilitates a non-judgemental acceptance of physical or psychological distress, thereby reducing the tendency to ruminate and catastrophise over these experiences.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Recognise that patients with multiple somatic complaints and abnormal illness behaviour are common in primary care.

-

Adopt a holistic, biopsychosocial approach when assessing such patients, seeking to understand the meaning and function of their multiple somatic complaints.

-

Pay attention to their adjustment, mood and anxiety as well as somatic symptom and related disorders, considering psychosocial interventions and antidepressants where indicated.

-

Empathically validate distress and normalise the mind-body connection. Explain clinical findings and reassure the patient that serious conditions have been ruled out.

-

Limit diagnostic testing, referrals to specialists and polypharmacy, as they may increase the risk of iatrogenic complications.

-

Collaborate with the patient in setting treatment goals and deciding on treatment options.

-

Schedule visits at regular intervals for patients with persistent symptoms.

-

Focus management on improving function and coping with the distressing symptoms rather than curing them.

Jane was initially fearful of being diagnosed with a mental illness. After building rapport with her primary care physician, she acknowledged the emotional distress that her symptoms were causing her. She was subsequently more receptive to interventions to reduce her anxiety, with the personal goal of being able to eat her favourite foods again. She was encouraged to concurrently continue proton pump inhibitor therapy for laryngopharyngeal reflux, as it helped reduce the discomfort and globus sensation. She was concurrently started on fluvoxamine 50 mg nightly and underwent eight sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy over three months. Jane’s anxiety and constant ruminations improved with these interventions. She no longer experienced any throat discomfort and returned to eating without any problems. Her weight gradually increased back to its premorbid baseline.

SMJ-62-258.pdf