Abstract

Behavioural problems in children are a relatively common occurrence but are a concern for parents. Such problems are often a reflection of the child’s social stressors, environment and developmental state. Although a majority of behavioural problems are temporary, some may persist or are symptomatic of neurodevelopmental disorders or an underlying medical condition. Initial management of behaviour problems often involves helping parents to learn effective behaviour strategies to promote desirable behaviours in their children. This article highlights a general approach to evaluating and treating behavioural problems in children in the primary care setting. Sleep problems, eating disorders, and other emotional and developmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, are not within the scope of this article.

Justin, aged two-and-a-half years, was brought to your clinic by his mother, who was concerned that he had had temper tantrums almost every day over the past six months. She reported that Justin would start to scream and shout when his demands were not met, and start hitting people around him and banging his head on the floor. This was causing significant distress to his mother and other caregivers, including his grandparents. Justin had been attending childcare since he was two years of age, but his teachers had not reported any concerns.

WHAT IS A PROBLEM BEHAVIOUR?

Early childhood is a phase of rapid development during which children develop motor skills, language and social skills. They learn to regulate emotions and, to some extent, control their behaviour. These skills help the children function in different settings. It is not uncommon for behavioural problems to emerge during this period, as children are trying to make sense of the world, assert their independence and adjust to various transitions such as making new friends or starting school.

Behavioural problems in children can be divided into externalising problems such as aggression, oppositional behaviour and hyperactivity, and internalising problems such as anxiety and depression.(1) Internalising problems are more likely to be picked up by parents, whereas externalising problems may be identified by parents or teachers.(2) In contrast to their Australian and American counterparts, who demonstrate an equal or greater number of externalising problems compared to internalising problems,(1,3) children in Singapore tend to demonstrate more internalising problems.(2)

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

Behavioural problems are commonly seen in children, occurring at a comparable estimate of about 12% in children from preschool to 12 years of age in Australia, the United States and Singapore, based on community samples.(1,2,3) However, low response rates on parent and teacher surveys, underreporting of problems by parents and exclusion of children with special needs may result in underestimation of this prevalence.(2) Although a majority of behavioural problems are temporary, some reports estimate that as many as 50% of preschool behavioural problems can become chronic and persist into adolescence and adulthood, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorders, which are in turn associated with substance misuse, family violence and crime.(1,3,4) Children presenting with behavioural problems can cause significant stress to caregivers and impact family functioning.(5) As primary care practitioners are the first point of contact when parents have concerns about their child’s development or behaviour, it is essential for them to be aware of the baseline strategies to manage behavioural problems.

HOW TO APPROACH A CHILD WITH PROBLEM BEHAVIOUR?

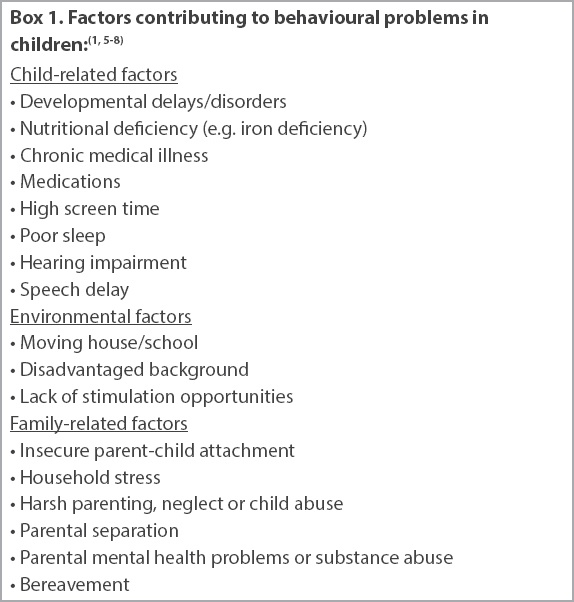

Parents are often concerned about whether their child is normal. However, the boundaries between normal development and clinically significant behavioural disorders can be challenging. Normal development may be inappropriately identified as a problem behaviour depending on the child’s age. Therefore, behaviours need to be interpreted in the context of the culture and developmental stage of the child.(3) Problem behaviours that are observed across two or more settings are significant and deserve further workup, whereas a behaviour problem in a single setting may be related to an issue specific to that setting.(1) Adverse childhood experiences arising from childhood abuse and neglect can also present as behaviour problems and cause maladaptive development.(6) Therefore, when assessing children who present with behavioural problems, a detailed clinical evaluation is necessary to identify child, family and environment-related factors, including developmental or health problems and social stressors contributing to the behaviour (

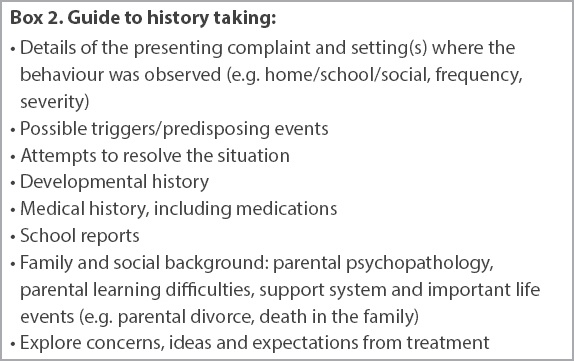

Taking a detailed history

The first step towards evaluating problem behaviours is to obtain a detailed account of the behaviours, including their frequency, severity, and impact on the child and family functioning.

Box 2

Guide to history taking

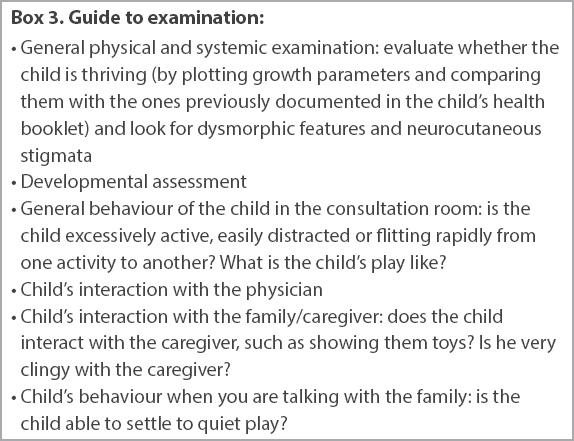

Behaviour observation and examination

In addition to a general physical examination and a developmental assessment, the behaviour of the child in the consultation room should be observed, including the child’s interaction with the family and the physician. However, keep in mind that some children may behave well when they are aware that they are being observed.

Box 3

Guide to examination

HOW SHOULD I MANAGE A PATIENT WITH PROBLEM BEHAVIOUR?

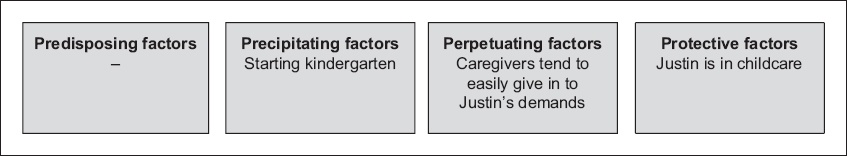

Management of the problem behaviour depends on the factors contributing to it, severity of presentation, impact of the behaviour on the child and family, and the family’s expectations. Some parents simply want reassurance that their child is normal, while others want specific behaviour management strategies. The information from the consultation can be organised into a four-P grid, which includes predisposing (vulnerability) factors, precipitating (triggering) factors, perpetuating (maintaining) factors and protective (resilience) factors to generate a treatment plan.(1,5) We applied the four-P grid to our case scenario and developed a management plan to help Justin’s parents address their concerns (

Fig. 1

Four-P grid shows analysis of our case scenario.

ABC’s of behaviour management

In general, a structured and rewarding environment promotes positive behaviour. Parents and caregivers thus need to set clear behaviour expectations and establish clear consequences for problem behaviours. Caregivers must then consistently follow through with the consequences. In order to manage problem behaviours effectively, parents should know how to identify the ABC’s: the antecedents (‘A’) or triggers (preceding event that makes the problem more likely to happen), the specific behaviours (‘B’) that need to be promoted or discouraged, and the consequences (‘C’) or actions taken following a specific behaviour, which will affect the likelihood of the behaviour happening again.

As children learn by example in the formative years, parents can model desirable behaviours and reinforce them with a reward system, such as a sticker chart. When using the reward system, be specific about the behavioural problems that the parents need to target and consider targeting 1–2 behaviours at one time. Children who obtain insufficient attention may alter their behaviour to receive negative attention by externalising through screaming, making a mess or fighting with a sibling. By paying attention to such a behaviour, the adult positively reinforces the behaviour (consequence) and further perpetuates it. Ignoring can be an effective parenting technique for such negative behaviours. An age-appropriate time-out period may also be suitable to allow the child to calm down and not gain additional attention for misbehaviour. Time-out durations of about 1–2 minutes per year of the child’s age are often recommended but not supported by evidence. Generally, time out should not be used for children aged below three years and must be limited to five minutes or less.(9) Loss of privileges (e.g. play, planned screen time) can also be used as an effective consequence to reduce undesirable behaviours.

Parents must be forewarned that the child’s behaviour may get more difficult before it starts to subside, but parents must remain calm and firm in their approach.(5) It may be difficult to reason with a child during a tantrum and parents must be mindful not to engage in coercive parent-child interactions or punish the child, as that may worsen behaviour.(10) Resources are available in the community for caregivers to engage help through parental support groups and group behavioural management workshops. Some community service centres such as Epworth Community Services, some Family Service Centres and the Dyslexia Association of Singapore organise parenting workshops that parents can attend. Websites such as

WHEN TO REFER TO A SPECIALIST?

Although not all problem behaviours warrant referral, some red flags and concerns warrant a review by a paediatrician, psychologist or psychiatrist. A referral is necessary when: (a) initial behavioural measures have failed; (b) the child is at risk of physical harm; (c) the behaviour is hindering the child’s functioning and development; (d) there are concerns about an underlying medical condition (e.g. sensory impairment, intracranial pathology, etc) or (e) there is suspicion of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety or depressive disorders, and oppositional defiant or conduct disorders; (f) parental mental health issues or complex family dynamics are present; (g) the childcare centre, kindergarten or school is concerned or has difficulty coping with the child’s behaviour; and (h) the behaviours are affecting family functioning.

CONCLUSION

Behavioural issues are often a cause for concern for parents and teachers and may be the first presentation of an underlying developmental or medical problem. It is important to thoroughly evaluate the presenting behavioural problem, including the social and environmental settings that may be triggering such behaviour in the child. Initial management often involves parental behaviour training to promote desirable behaviours by implementing simple behaviour strategies. However, we should refer the child to a specialist if we are concerned about the child’s safety or development, or if initial behavioural management strategies fail to resolve the behavioural problems.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Behaviour problems are common in childhood as a child is developing and trying to adjust to the environment. If not appropriately addressed, they can become chronic and persist into adolescence and adulthood.

-

Behavioural problems in children can be an early presentation of developmental, learning or mental health problems and may reflect the presence of social stressors in the environment. There may also be an underlying medical problem.

-

It is important to discuss the concerns and expectations of the family when deciding how to manage the behavioural problems.

-

Common behaviour problems can be effectively managed by behaviour interventions, including rewarding desirable behaviours and following through with effective consequences to reduce undesirable behaviours.

-

We must consider referring a child for further specialist evaluation if initial behaviour management strategies fail or if we have concerns about the child’s safety or development.

You reassured Justin’s parents and provided them with a behaviour management plan consisting of ignoring undesirable behaviour and incentivising good behaviour with a reward programme. You advised that all caregivers should be consistent in managing Justin’s behaviours. You noticed that Justin appeared to be thriving. He interacted well with his mother, made good eye contact and responded to you during the consultation. A general and systemic examination was unremarkable. You did not notice any abnormal or challenging behaviour during your consultation.

SMJ-60-172.pdf