Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterised by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour and interests. Early detection and early intervention programmes improve functional outcomes. Family physicians should screen for ASD opportunistically when children attend clinics for acute issues and during scheduled well-child assessments. Early warning signs of ASD include the lack of social gestures at 12 months, using no meaningful single words at 18 months, and having no interest in other children or no spontaneous two-word phrases at 24 months. Children with suspected ASD should be referred to appropriate specialist centres as early as possible for multidisciplinary assessment and diagnosis.

Nicky, a 12-month-old boy, came with his mother to your clinic. He had a four-day history of cough and sore throat. His mother mentioned in passing that Nicky had always been a quiet child who made poor eye contact with her. Nicky was very quiet throughout the consultation and neither smiled nor waved at you or his parents. He did not seem to respond to you calling his name. Other than a mildly injected pharynx, he had no abnormalities on physical examination and no dysmorphic features.

WHAT IS AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER?

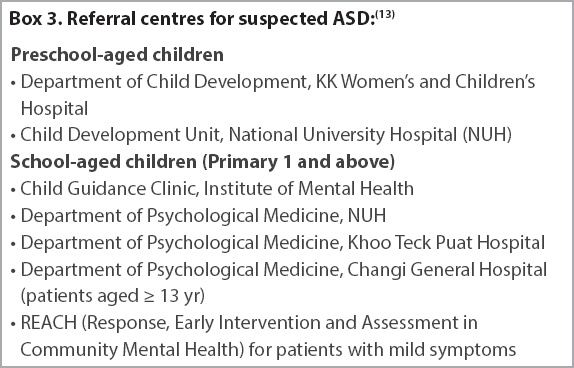

‘Autism’, derived from the Greek word ‘autos’, or ‘self’, refers to someone who ‘lives in a world of his own’. Hence, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects a person’s ability to make sense of the world and relate to other people. It is characterised by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour and interests. These manifest during the early developmental period and cause clinically significant impairment of social and occupational function (

Box 1

Features of autism spectrum disorder

The exact aetiology of ASD is unknown; it is thought to have strong and complex genetic underpinnings with modulation of phenotypic expression by environmental factors.(3) Normal childhood vaccines have been falsely implicated in the causation of ASD, and extensive research has now proven no link between vaccination and ASD.(4) Factors associated with increased risk of ASD include:(5) male gender; family history of sibling or parent with ASD; advanced paternal and maternal age; prematurity (gestational age < 35 weeks) or antenatal infections; antenatal exposure to medications (e.g. valproate and antidepressants); and genetic syndromes such as fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Rett syndrome, Down syndrome, muscular dystrophy and neurofibromatosis.

ASD is not uncommon. Based on local data from KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and National University Hospital, the prevalence of ASD in Singapore is estimated to be one in 100 individuals, and most children are formally diagnosed at approximately three years of age.(6)

WHY IS EARLY DETECTION IMPORTANT?

Early detection is important because early diagnosis and early intervention programmes have been shown to improve functional outcomes and quality of life.(7,8) Unfortunately, early diagnosis of ASD can be challenging. It is often diagnosed after the age of three years, despite caregivers raising concerns for possible ASD at 15–22 months.(9,10) The presentation of ASD can differ greatly from one child to the next. Some are perceived by parents as ‘different’ during the first few months of life, while others present with delayed language development during the second year of life, and still others develop normally until 12–24 months but regress thereafter (‘autistic regression’). Locally, early diagnosis of ASD can be challenging when parents have poor awareness of the early symptoms of ASD or when they may not be the main caregivers; for instance, when working parents rely on the support of grandparents or domestic helpers. In such cases, the physican can consider taking collaborative histories from these caregivers.

The role of primary care in early detection

Being at the frontline of community healthcare, family physicians are well placed to screen for ASD. Family physicians can opportunistically look for features of ASD when children attend clinics for acute issues, and systemically screen for ASD during scheduled well-child developmental assessments. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-up, (i.e. M-CHAT R/F)(11) is one such screening tool. It has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for use during scheduled well-child assessments at 18 and 24 or 30 months, and is validated for use in the Singapore population.(12)

WHAT ARE THE EARLY SIGNS?

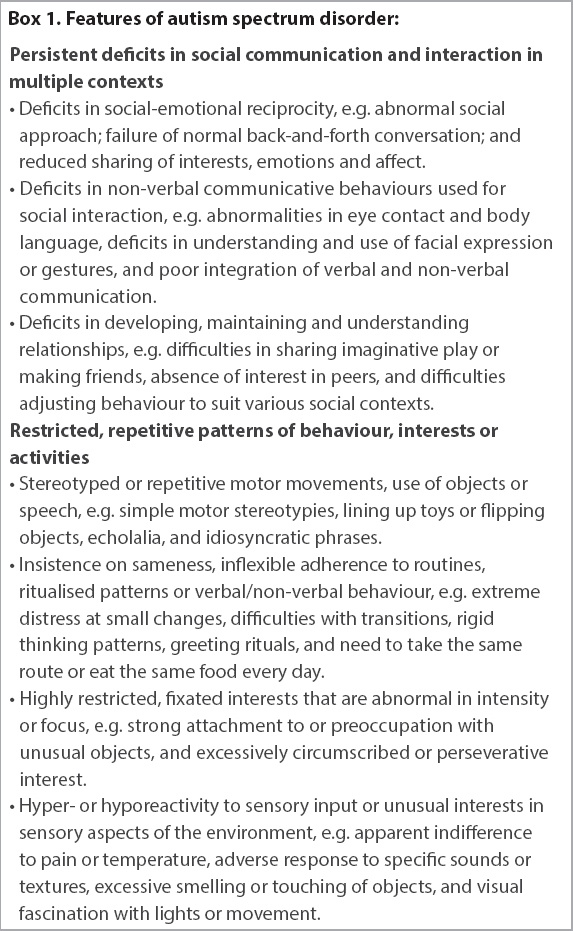

As some children with ASD have good verbal ability, the condition is easily missed. Therefore, maintain a high index of suspicion for ASD in children with atypical language (e.g. echolalia, pronoun reversal, calling self by name or only talking about topics of their own interest), poor social interaction, and rigidity in thought or behaviour. The early warning signs of ASD are summarised in

Box 2

Early warning signs for autism spectrum disorder

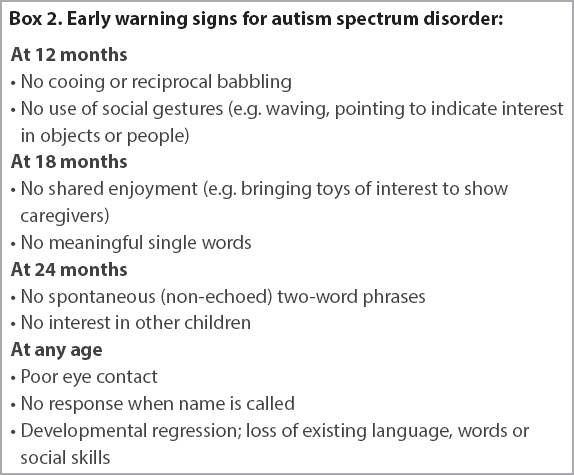

WHAT SHOULD I DO IF I SUSPECT ASD?

If ASD is suspected, the child should be referred to appropriate specialist centres for a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment and diagnosis. In addition to public sector centres (

A number of other conditions (e.g. intellectual disability, social communication disorder and developmental language disorder) mimic ASD, in that they also impair social communication, social interaction and/or may be associated with stereotypic behaviours. It is important for the specialist centres to distinguish between ASD and these conditions, as the more subtle differences may be beyond the scope of the family physician.

WHAT EARLY INTERVENTIONS ARE AVAILABLE FOR CHILDREN?

Many children with ASD benefit from early intervention, including intensive structured teaching and practice in social interaction, communication, thinking, self-help and independence. Many interventions that have evidence of benefit are available, including occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, Picture Exchange Communication System, the TEACCH® (Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children) programme and applied behavioural analysis. In Singapore, these interventions are largely administered within small-group settings in EIPIC (Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children) centres. There are many EIPIC centres across Singapore, run by both government-funded voluntary welfare organisations (VWOs) and private operators. Children with ASD can also receive these interventions via individual therapy if needed. Providers of individual therapy include those in the private sector and VWOs such as the Thye Hua Kwan Children’s Therapy Centre and SPD’s Continuing Therapy Programme.

Some children with ASD have mild developmental needs. For these children, shorter-term, school-based intervention programmes such as the Development Support and Learning Support programme prepare them for mainstream primary school education. We recommend visiting the SG Enable website on ‘Services for Children with Special Needs’ for the most current information.(14) The Autism Resource Centre (Singapore) website is also a useful resource for parents.(15)

HOW CAN INDIVIDUALS WITH ASD BE SUPPORTED?

Support for children with ASD continues in their schooling years and beyond. Some students will be able to learn with their peers in mainstream schools, with support from allied educators. Others require more specialised learning environments in special education schools (e.g. Pathlight School, Eden School, St Andrew’s Autism Centre, Rainbow Centre and AWWA [Asian Women’s Welfare Association] School), which allow them to learn in a more individualised manner with time and opportunity to apply the skills they learn.

As a child with ASD enters adolescence and adulthood, there is a continued need for support and guidance – for instance in negotiating higher education options, meeting work productivity demands, achieving vocational skills through job coaching, understanding and complying to social rules and expectations, developing positive relationships with others, understanding and coping with sexuality issues, and managing stress.

With training, placement and support, people with ASD can find employment in an area that matches their abilities and interests. Locally, the Employability and Employment Centre offers job training, placement and support for adults with ASD. More information is available at its website.(16)

Support from the family physician for individuals on follow-up

Children with ASD may consult family physicians for common ailments such as cough or diarrhoea. As they may have difficulty expressing themselves and in communicating their symptoms to caregivers and physicians, physicians should be alert for varied presentations of illness.

Beyond managing acute conditions, family physicians have a role in the continued support of children who are on follow-up with specialist services for ASD. Firstly, they should check that the child remains on active follow-up and continues to receive interventions, and reinforce the importance of doing so. Secondly, they should ensure that the child receives all vaccinations as per the national childhood immunisation schedule. Some parents may require reassurance that there is no link between vaccination and ASD. Thirdly, the family physician can also explore how the child’s family is coping. Family is the cornerstone to the care of these children: it is they who partner with therapists to incorporate interventions taught during therapy into the child’s daily routine. The family physician cares for the entire family. Look for stressors such as parenting, marital, financial and parental mental health issues, with a view to referring family members to appropriate counselling and support services (e.g. family service centres) if needed. Finally, adolescents and adults with ASD may have comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder that may need to be identified and addressed.

IS THERE A ROLE FOR COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE?

Parents of children with ASD may express an interest in the use of complementary and alternative medicine, including biologically-based (e.g. dietary supplements; traditional Chinese medicine; gluten-free, casein-free diet; acupuncture; chelation therapy; and transcranial magnetic therapy) and non-biologically-based (e.g. art therapy and sensory integration therapy) modalities. As evidence for the efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine in ASD is sparse, the physician should not make any evidence-based recommendations on their use.(17) Instead, families can be encouraged to share all interventions that they are pursuing with their physicians. Some non-biologically-based modalities (e.g. art therapy and music therapy) resemble normal childhood experiences and probably do no harm. Biologically-based therapies, including supplements, may result in harm and should be monitored for side effects and potential drug interactions.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Family physicians have a role in the early detection of ASD. Apart from conducting well-child developmental assessments, they should screen for ASD opportunistically when children attend clinics for acute issues and pay attention to any concerns raised by caregivers.

-

When screening for ASD in very young children, look for delayed non-verbal developmental milestones (e.g. no waving, pointing, eye contact or spontaneous sharing by 12–18 months) and impaired social interaction (e.g. lack of interest in other children).

-

If ASD is suspected, refer the child to appropriate specialist centres as soon as possible.

-

Early interventions are available for children with ASD and have been shown to improve functional outcomes. Individuals with ASD can become productive, functional members of society with ongoing support.

Through further history-taking, you established that Nicky’s parents had never observed him pointing to indicate his needs. Nicky was said to exhibit hand flapping when excited and did not tell others about his interests. You suspected early features of autism spectrum disorder and referred Nicky to the Department of Child Development at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital for further assessment. He was enrolled in the Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children and subsequently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Four years later, you saw Nicky again for cough and fever. He had made significant progress in language development and social behaviour. He was preparing to enrol in preschool and was expected to join a mainstream primary school later on.

SMJ-60-328.pdf