Abstract

Any medical diagnosis should take a multimodal approach, especially those involving tumour-like conditions, as entities that mimic neoplasms have overlapping features and may present detrimental outcomes if they are underdiagnosed. These case reports present diagnostic pitfalls resulting from overdependence on a single diagnostic parameter for three musculoskeletal neoplasm mimics: brown tumour (BT) that was mistaken for giant cell tumour (GCT), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis mistaken for osteosarcoma and a pseudoaneurysm mistaken for a soft tissue sarcoma. Literature reviews revealed five reports of BT simulating GCT, four reports of osteomyelitis mimicking osteosarcoma and five reports of a pseudoaneurysm imitating a soft tissue sarcoma. Our findings highlight the therapeutic dilemmas that arise with musculoskeletal mimics, as well as the importance of thorough investigation to distinguish mimickers from true neoplasms.

INTRODUCTION

As clinicians’ diagnoses have profound impact on patients’ health, it is in the patients’ best interest that diagnoses are as accurate as possible. In musculoskeletal oncology, it is not uncommon to have similar presentations of different conditions in terms of clinical, radiological and histological findings. This complicates the decision of how to manage the condition since several different diagnoses need to be entertained. For example, in tumour-like conditions, a benign entity can simulate a malignant neoplasm and vice versa. To differentiate one from the other is of paramount importance, as a wrong diagnosis is potentially hazardous to the patient. The key to achieving this is familiarising oneself with such mimics and considering all diagnostic parameters before proceeding to definitive management. Herein, we present multiple instances involving tumour-like conditions where the initial diagnosis was made based solely on one outstanding diagnostic parameter. We discuss the factors contributing to these diagnostic complications with the aim of making clinicians more aware of and sensitive to the possible pitfalls in their diagnoses, thus improving their practices.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 36-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to her district hospital with a painful lump on the proximal left leg. It was first noticed two years prior to consultation and was associated with generalised myalgia and mechanical low back pain. She had no previous history of trauma, fever, cough or constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed a tender, hard, fixed, 5 cm × 5 cm mass with no overlying skin changes on the anterior aspect of her proximal left leg. The range of motion of her left knee was limited due to pain. Examination of her back elicited tenderness at the L4 and L5 region with no neurologic signs.

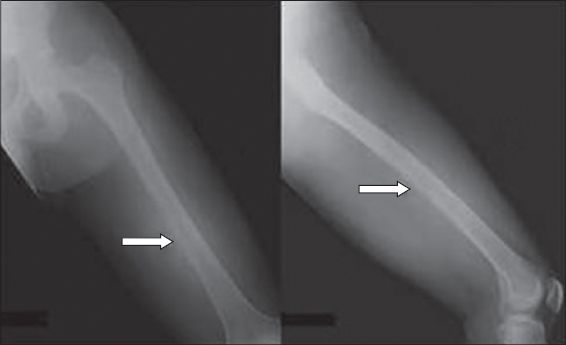

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographic views of her left tibia and fibula performed at the same hospital showed a well-defined, eccentric, lytic epiphyseal lesion of the left tibia (

Fig. 1

Case 1. Plain radiograph of the left tibia shows a lytic lesion at the epiphysis of the proximal tibia (arrow), with the lesion poorly demonstrated on anteroposterior view.

At our centre, the patient underwent a core needle biopsy of the left tibia, and the tissue sample was sent for culture and histopathological examination (HPE). Tissue HPE showed a proliferation of spindle stromal cells with nuclei features similar to those of a giant cell and osteoclastic giant cells around bony trabeculae, suggestive of a giant cell-like lesion. When we correlated the patient’s history of generalised bone pain with the generalised diffuse osteopenia on her radiograph, brown tumour (BT) was added to the differential diagnosis and she was screened for hyperparathyroidism. Blood investigations revealed a high alkaline phosphatase value of 1,185 IU/L, a high calcium level of 3.13 mmol/L, a low phosphate level of 0.6 mmol/L and a very high parathyroid hormone level of 163 pmol/L. Further investigations were conducted to confirm BT. A skeletal survey, including a plain radiograph of the hand, showed phalangeal tuft resorption of distal phalanges but no obvious subperiosteal bone resorption (

Fig. 2

Case 1. Radiograph of the hand shows phalangeal tuft resorption of the distal phalanges (arrows) of the middle and ring fingers.

A diagnosis of BT secondary to primary hyperparathyroidism was made. The patient was referred to the endocrinology team for management of hyperparathyroidism and parathyroidectomy was performed. In view of an impending pathological fracture, she underwent curettage and cementation of the left tibia. Three years after the procedure, she was well with no evidence of relapse.

Case 2

A 28-year-old man presented with a two-week history of progressive pain and swelling on the left thigh, associated with intermittent fever. The pain had started off as a deep, boring pain that was worse during rest or at night and soon progressively worsened until the affected limb was unable to bear weight and the man became wheelchair-bound. He also experienced loss of appetite and weight. An anteroposterior radiograph revealed an osteolytic lesion involving the mid-shaft of the left femur, with cortex erosion and periosteal reaction (

Fig. 3

Case 2. Plain anteroposterior radiograph shows an osteolytic lesion involving the mid-shaft of the left femur (arrows), with cortex erosion and periosteal reaction.

Upon admission, a biopsy was scheduled. However, during detailed history-taking, it was revealed that the patient had had prolonged contact with deer carcasses following his hunting expedition in a rural forest two weeks before he had the symptoms. He claimed that his hunting partner had developed similar symptoms with similar onset. However, no further information could be obtained as his partner was uncontactable. Otherwise, his medical history was unremarkable. Clinically, he was febrile. His left thigh was tender and warm with a deep, ill-defined swelling measuring 20 cm × 8 cm, but without discharging sinuses. No other skin or soft tissue lesions were noted. Movement was restricted in his left knee due to pain.

Blood investigation revealed leucocytosis (17.7 × 109/L) with 86% neutrophils, and raised inflammatory markers with a C-reactive protein (CRP) level and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 45.6 mg/dL and 140 mm/hr, respectively. In view of the radiographic findings, further imaging tests were ordered. MR imaging showed a lesion involving the mid-shaft of the left femur, including the surrounding circumferential soft tissue. A bone scan demonstrated isolated uptake of the left mid and distal femur. A core needle biopsy was performed and the tissue sample was sent for histopathology, culture and acid-fast bacilli tests. Both blood and bone biopsy cultures grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and a diagnosis of MRSA osteomyelitis was made.

The patient was immediately commenced on intravenous (IV) vancomycin based on sensitivity results. Incision and drainage was performed for the left thigh abscess. Culture of pus also yielded MRSA. There was no other investigative evidence that pointed to malignancy or other infections, especially tuberculosis. After a total of 12 weeks of IV vancomycin and 12 weeks of oral rifampicin and fusidic acid, totalling six months of anti-MRSA therapy, ESR and CRP level were completely normalised. During subsequent months, the left thigh pain improved and he was able to ambulate. Two years after the treatment, he had regained full function of his lower left limb with no evidence of recurrence.

Case 3

A 57-year-old woman with no known medical illness was referred for a swelling of the right calf that was progressively enlarging. It was noticed two months prior to consultation. The swelling was associated with occasional throbbing pain when she walked long distances but not when she was at rest. She had no fever and no constitutional symptoms. There was also no history of recent trauma. However, five years prior to this consultation, she had sustained a closed fracture of the right tibia, which had been treated conservatively with a cast. On examination, we found a right calf swelling that was non-mobile, firm, warm, non-tender and measuring 10 cm × 10 cm. Neurovascular and systemic examinations were unremarkable.

She had initially presented to her nearest hospital, where radiography was performed, which showed a poorly defined tibial lesion with cortical erosion and scalloping of the tibia (

Fig. 4

Case 3. Radiograph shows scalloping of the tibia due to gradual chronic pressure of the pseudoaneurysm (postoperatively).

Initial core needle biopsy results at our centre were inconclusive and the patient was scheduled for an open biopsy. Intraoperative findings, however, revealed a pseudoaneurysm arising from the old tibial fracture and lacerated posterior tibial artery. Bone callous formation of the healed tibial fracture was noted to impinge on the blood vessel. The pseudoaneurysm was excised and the patient was treated with a one-week course of IV cefuroxime. Two years after the treatment, she was well with no complications or recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Clinicians are often required to make rapid decisions following a diagnosis and hence are susceptible to diagnostic pitfalls that can affect clinical outcomes. Most often, misdiagnoses occur due to overreliance on a single, often outstanding, diagnostic parameter, resulting in potential catastrophe for patients. It is therefore imperative to treat diagnoses in a multimodal way and adopt a comprehensive approach with patients, especially when tumour-like conditions further complicate the decision-making process.

In the first case, BT was initially diagnosed as GCT. As GCT and BT share many radiological and histopathological features, the misinterpretation is not surprising, especially with BT having a reported incidence of only 0.1%.(1) A literature search of the MEDLINE database revealed 17 reported cases where BT had been mistaken for either GCT, giant cell granuloma, primary malignancy or metastatic bone disease, with five cases of BT mistaken for GCT.(1-5) Although it closely resembles malignancy, BT is a non-neoplastic, focal manifestation of persistent hyperparathyroidism, where altered osseous metabolism is characterised by the presence of subperiosteal resorption, diffuse osteopenia and BT. Distinguishing between GCT and BT can be difficult as both usually appear as expansile, well-marginated, osteolytic, epiphyseal lesions on plain radiographs. Histologically, both GCT and BT are composed of mononuclear stromal cells and characteristic multinucleated giant cells. The only additional feature of BT on radiographs is manifestations of hyperparathyroidism, which includes subperiosteal resorption, but they were not evident in our patient. As both imaging and HPE results were highly suggestive of GCT, a diagnosis of GCT was made. BT was only diagnosed later through biochemical testing, when the findings were correlated with a history of generalised bone pain and radiographic evidence of generalised osteopenia. Fortunately for the patient, she recovered fully after undergoing curettage and cementation. Resection of the lesion is advocated for management of BT, as there have been cases where the condition became worse following parathyroidectomy or normalisation of parathyroid level.(6)

In the second case, the patient had MRSA osteomyelitis, but the initial clinical impression was osteosarcoma. Osteomyelitis is a non-neoplastic condition that can mimic tumours. A MEDLINE database search revealed that there were 24 reported cases of adult osteomyelitis simulating a sarcoma and vice versa to date, and four in which osteomyelitis mimicked osteosarcoma.(7-10) This could be due to the nonspecificity of symptoms such as fever, bone pain and loss of weight, and osteomyelitis appearing malignant on imaging. On radiographs, it has an aggressive, permeated and moth-eaten appearance associated with periosteal reaction and cortical erosion. On MR imaging, it appears to extend into surrounding soft tissue and on bone scans, it demonstrates intraosseous extension. Although the imaging findings were highly suggestive of malignancy, one should take into account the patient’s history of activities, especially those involving animals. In this case, the patient was heavily involved in rural deer hunting expeditions and was exposed to various possible infections. It was found that both blood and bone tissues were infected with MRSA. Fortunately, the patient recovered fully following appropriate anti-MRSA therapy.

A pseudoaneurysm, defined as a pulsating, encapsulated haematoma in communication with the lumen of a ruptured vessel, is another example of how a benign process can simulate neoplasm. Although it is relatively rare, with a prevalence of less than 3%,(11) a literature search of the MEDLINE database for all years found five reports of pseudoaneurysm mimicking a soft tissue sarcoma.(12-16) In the third case, a premature referral for malignant fibrous histiocytoma was made based purely on the MR imaging finding that the right calf showed malignant bone lesion features, without correlating with histopathology or clinical history. Fortunately for the patient, an open biopsy was planned, where it was discovered intraoperatively that the source of the swelling was in fact a pseudoaneurysm arising from an old tibial fracture and lacerated posterior tibial artery, allowing the pseudoaneurysm to be safely resected before an impending rupture.

In summary, our reported cases show the importance of comprehensively correlating all diagnostic parameters for a definitive diagnosis, especially in cases where there are tumour-like conditions. Such diagnostic pitfalls can be easily avoided and this will lead to improved patient care.