Abstract

Infant social, emotional and neurological development is shaped by the mother-child dyad. Dysfunction in this bond, as well as maternal mental health problems, can negatively impact child development. The family physician is well-placed to spot dysfunction in the mother-child dyad and screen for postnatal depression during well-child visits. If any issues are identified, the family physician can provide support and help the mother-child dyad to access community resources and specialist psychiatric services.

At Adam’s 12-month vaccination, your clinic nurse highlighted that his mother, Sara, seemed preoccupied in the waiting area. Adam began to cry but Sara only responded when his wails grew louder. She pushed his pacifier into his mouth rather mechanically and rocked his stroller back and forth on the spot. When they entered your room, Sara seemed rather stiff as she lifted Adam up from his stroller for your examination. Adam sat still in her lap, sucking his pacifier as he stared blankly at the Snellen chart on your clinic wall. He did not make any sound throughout the consultation. Sara looked tired and gave brief answers when asked about Adam’s development.

WHAT IS THE MOTHER-CHILD DYAD?

The mother-child dyad – the mother-offspring unit – share an intimate biological, social and psychological relationship. It is no surprise that infant social, emotional and neurological development is shaped by the bond established between mother and child. The quality of this attachment, often reflected in the level of maternal emotional availability, maternal sensitivity and responsiveness to infant cues, determines how infants learn, form relationships, experience the world and regulate their emotions. For example, young children demonstrate ‘social referencing’, in that they use parents’ emotional expressions as guides in approaching or withdrawing from physical and social stimuli.(1) In an unfamiliar situation, a mother’s emotional availability has a positive effect on the infant’s affective, social and exploratory behaviours. Conversely, a physically present but emotionally unavailable mother invokes displeasure and inhibits her child’s exploration.(2,3)

Infants who learn that their social initiatives are successful in getting a reciprocal response from their attachment figure are likely to be more secure, active and happy in their interactions; they also show more attentional engagement with their caregiver, fewer resistant behaviours and greater physiological regulation in response to stress.(4) Mothers do not need to be perfect, just ‘good enough’ to provide a secure base.(5)

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT TO MY PRACTICE?

Maternal mental health is closely linked to child mental health and development. One in eight mothers experience postpartum depression.(6) Mothers with depression have been found to be less attuned to their infant’s needs, demonstrate poorer responsiveness to infant cues, and display more negative, hostile or disengaged parenting behaviours. This is in turn associated with lower cognitive functioning and adverse emotional development in their children.(7,8)

Short lapses in caregiving can be compensated for, but persistent attachment difficulties can cause longstanding ramifications. This is because neuroplasticity is highest in the first thousand days of a child’s life, beyond which it becomes progressively harder to reverse any adverse adaptations that the child may have made in response to its mother’s lack of attunement.(9) Children whose mothers had persistent and severe depression (as compared to children of mothers with transient postnatal depression) were at increased risk of behavioural problems by age 3.5 years, increased risk of depression in adolescence(10) and increased risk of stunted growth.(3,11)

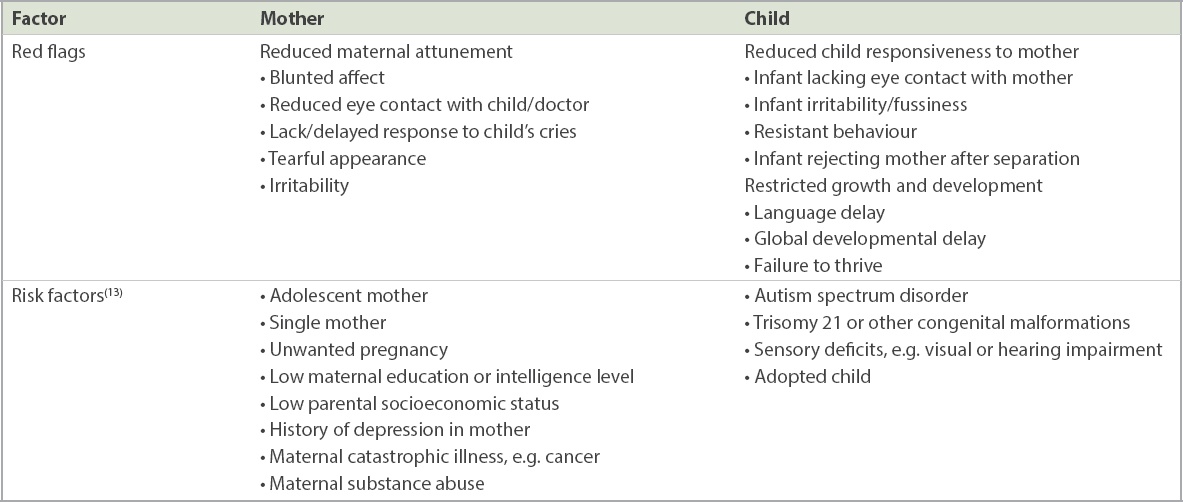

WHAT ARE THE RED FLAGS AND RISK FACTORS TO LOOK OUT FOR?

Risk factors for dysfunction in the mother-child dyad include medical and psychiatric illness in both mother or child, as well as challenging socioeconomic circumstances.(12) Red flags to look out for include reduced maternal attunement, reduced child responsiveness to the mother, and restricted child growth and development (

Table I

Red flags for dysfunction in the mother-child dyad.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

The family physician is well-positioned to identify at-risk or dysfunctional mother-child dyads, and intervene to change the trajectory through touchpoints such as scheduled well-child developmental assessments, the routine postnatal check and ad-hoc consultations for acute illnesses.

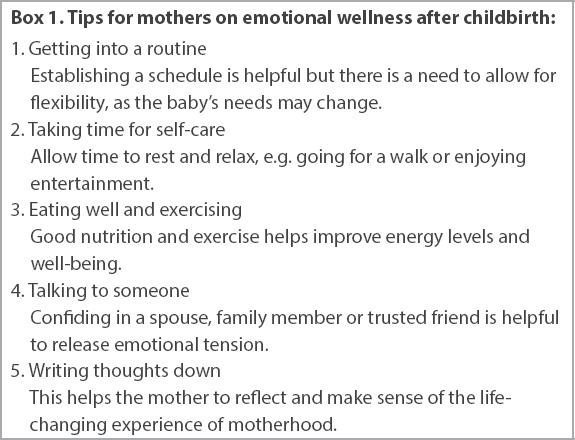

Simple tips to support the new mother (

Box 1

Tips for mothers on emotional wellness after childbirth:

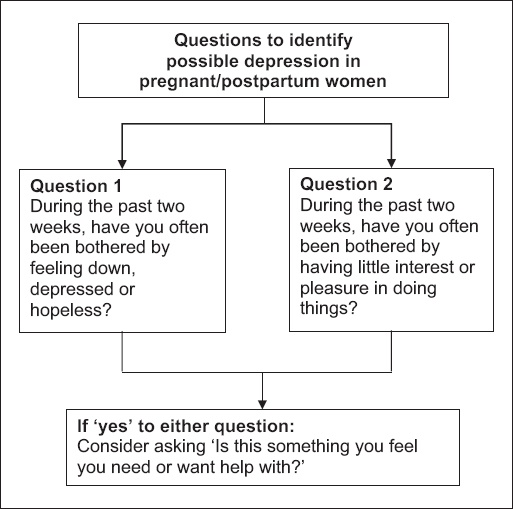

Scheduled well-child developmental assessments are an opportune time for the family physician to screen the mother for postnatal depression, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.(14) In Connecticut, a well-established programme sited at a community health centre screens mothers for depression during pregnancy, at the routine six-week postpartum visit and during the infants’ well-child visits.(15) Locally, the Integrated Maternal Child Wellness Programme, a novel collaboration between SingHealth Polyclinics and KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital’s (KKH) Department of Paediatric Medicine and Women’s Mental Wellness Service, uses a two-question screen (Patient Health Questionnaire 2) for maternal depression during scheduled well-child visits at Punggol Polyclinic (

Fig. 1

The Patient Health Questionnaire 2 screen for maternal depression.

Early identification of mothers with depression is important so that they can be connected to services that might mitigate the impact of the depression on the mother-child dyad. Studies of maternal depression screening in paediatric practice suggest that (a) it is feasible; (b) it yields a significant number of mothers who require intervention; and (c) intervention is effective, translating into positive child outcomes.(15) Locally, a screening and early intervention programme for postnatal depression in KKH (established since 2008) has shown improved clinical outcomes in the affected mothers’ symptoms, function and quality of life.(17)

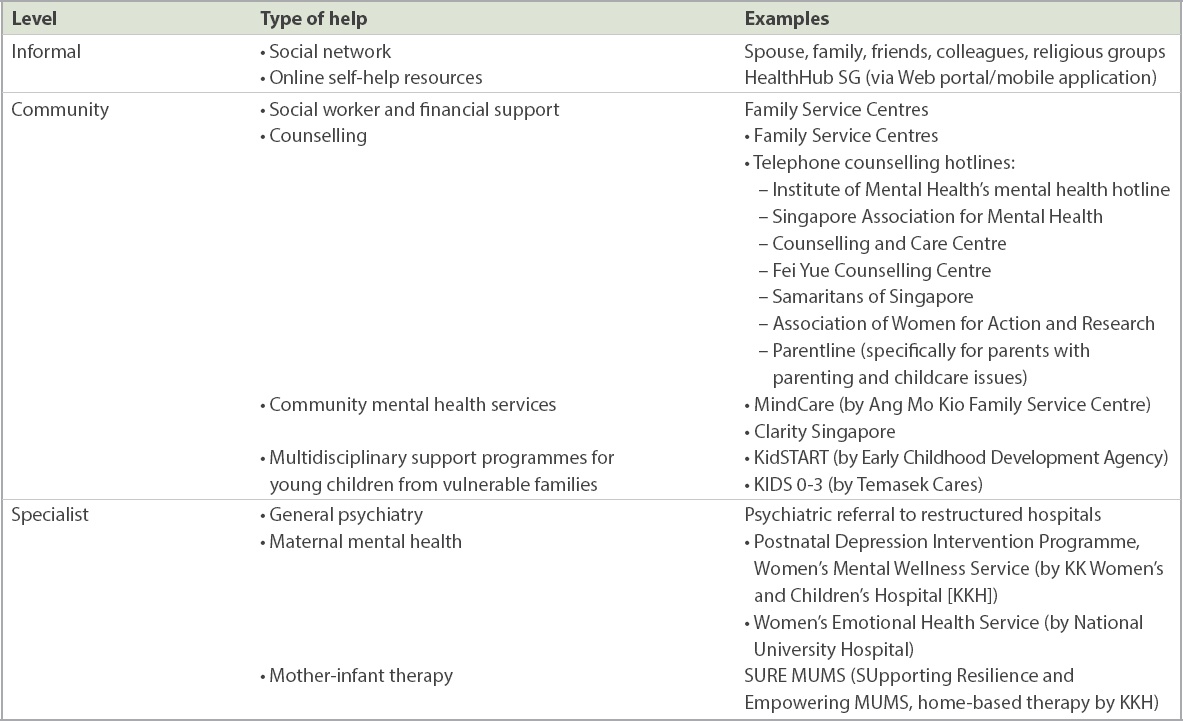

WHAT RESOURCES ARE AVAILABLE FOR MOTHER-CHILD DYADS?

At an informal level, the family physician can encourage the mother to engage her spouse and family for support, especially senior members for their advice and experience. Enlisting the help of friends, colleagues or religious group members (educating and equipping them if necessary) can also be useful. Community support resources include Family Service Centres, counselling hotlines, community mental health services and other support programmes (

Table II

Safety net of resources according to type of help provided.

If it appears that psychiatric attention will be beneficial, the family physician should offer to refer the mother to psychiatric services that are available in all restructured hospitals. Subspecialised services for maternal emotional and mental health are also offered at KKH and National University Hospital.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Persistent attachment difficulties in mother-child dyads, as well as maternal mental health problems, can lead to long-term consequences for the child’s mental health and development.

-

Red flags for dysfunction in mother-child dyads include reduced maternal attunement, reduced child responsiveness to the mother, and restricted child growth and development.

-

The family physician can screen for dysfunction in the mother-child dyad and maternal depression during scheduled well-child visits.

-

Early identification of maternal depression facilitates intervention and can translate into positive child outcomes.

-

Resources to support mother-child units include informal help from family and friends, community resources, and specialist psychiatric services.

You noted Sara’s blunted maternal affect and reduced material response to the child’s cries. Further history-taking revealed stressors including marital conflict and financial distress. Sara acknowledged that she often feels ‘down’. You gently suggested some tips on self-care and referred Sara to the postnatal depression intervention programme at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and the Family Service Centre for financial assistance and marital counselling. Sara and Adam returned six months later for Adam’s 18-month-old developmental assessment. This time, Sara chatted with you while keeping watch on Adam as he happily explored your room. Adam discovered a stray tongue depressor and triumphantly turned to show it to Sara, who smiled encouragingly before firmly instructing him to return it to you. You found that Adam met all developmental milestones and gladly shared this with Sara as a form of affirmation.

SMJ-60-501.pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr How Choon How for his invaluable thoughts and feedback in the writing of this paper.