Abstract

Developmental delays are common in childhood, occurring in 10%–15% of preschool children. Global developmental delays are less common, occurring in 1%–3% of preschool children. Developmental delays are identified during routine checks by the primary care physician or when the parent or preschool raises concerns. Assessment for developmental delay in primary care settings should include a general and systemic examination, including plotting growth centiles, hearing and vision assessment, baseline blood tests if deemed necessary, referral to a developmental paediatrician, and counselling the parents. It is important to follow up with the parents at the earliest opportunity to ensure that the referral has been activated. For children with mild developmental delays, in the absence of any red flags for development and no abnormal findings on clinical examination, advice on appropriate stimulation activities can be provided and a review conducted in three months’ time.

Jason, a three-year-old boy, was brought by his mother to your clinic to seek advice regarding his speech delay. She was concerned because his preschool teachers had told her that he seemed to be slow in speech compared to his classmates. Jason had a vocabulary of about 10–12 words and had not started speaking in phrases. He could respond to his name and followed simple instructions well. A physical examination found that he had no dysmorphic facial features and was in good health. He had attained all other developmental milestones appropriate to his age except for expressive language.

WHAT IS DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY?

Developmental delay occurs when a child does not achieve developmental milestones in comparison to peers of the same age range. The degree of developmental delay can be further classified as mild (functional age < 33% below chronological age), moderate (functional age 34%–66% of chronological age) and severe (functional age < 66% of chronological age).(1) A significant delay is defined as performance that is two or more standard deviations below the mean on age-appropriate standardised norm-referenced testing (usually conducted in secondary or tertiary care settings).(2)

The delay can be in a single domain (i.e. isolated developmental delay) or more than one domain. A significant delay in two or more developmental domains affecting children under the age of five years is termed global developmental delay (GDD).(3) Other patterns of abnormal development include: developmental disorder; developmental arrest and regression; and developmental disability. In developmental disorders, development does not follow the normal pattern, such as in a child with autism who has language abilities but is unable to use it for social interaction and communication purposes. Developmental arrest and regression refers to a normal developmental phase in a child that is followed by a failure to develop new skills or even loss of previously acquired skills. Regression is an unequivocal red flag and warrants an urgent referral to a specialist for further assessment and management. Not all children with developmental delay will have a developmental disability, which refers to severe, lifelong impairment in areas of development that affects learning, self-sufficiency and adaptive skills. Developmental delays can be transient, such as during a phase of prolonged illness, or persistent.

Variations in patterns of development

Some children may not follow the normal pattern of development. These variants include ‘bottom shufflers’, who do not crawl but shuffle around. These children tend to walk late and may be mildly hypotonic, especially in the lower limbs. Some ‘commando crawl’, while others do not go through the crawling phase at all. Children may exhibit variation in their rate of acquisition of language, social skills, play and behaviour, as they may follow a familial pattern (e.g. family history of speech delay) or be affected by environmental influences (e.g. not attending a preschool). There is a general belief that boys tend to acquire language later than girls, which has not been proven true.(4) Children coming from bilingual families may seem to have delayed acquisition of one language, but they eventually catch up in the absence of any risk factors. Nevertheless, physicians should be aware of the red flags in the context of the child’s development when determining a further management plan.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

Singapore does not have a national database to track the prevalence of developmental delays or disability. However, based on data from other developed countries, developmental delays are reported to occur in 10%–15%(5) and GDD in 1%–3%(1,3) of children under the age of five years. Various factors determine the prognosis or eventual outcome of children with developmental delay. These include the cause of the delay (i.e. is it a treatable cause, such as nutritional deficiencies), areas in which the child is delayed, how significant the delay is, the age at which the child commenced an intervention, and the extent of parental and caregiver involvement. If developmental delays are detected late, opportunities for early intervention are lost, resulting in poor outcomes such as learning difficulties, behaviour problems and functional impairments later on in life.(6) There is strong research evidence suggesting that effective early identification of developmental delays and timely early intervention can positively alter a child’s long-term trajectory.(7)

Primary care physicians play a significant role in early identification of developmental delays, both through developmental screening and routine developmental surveillance. Hence, it is essential that they have the knowledge and skills to identify developmental delays and provide an appropriate management plan to the family, including counselling the parents if necessary.

WHAT CAUSES DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY?

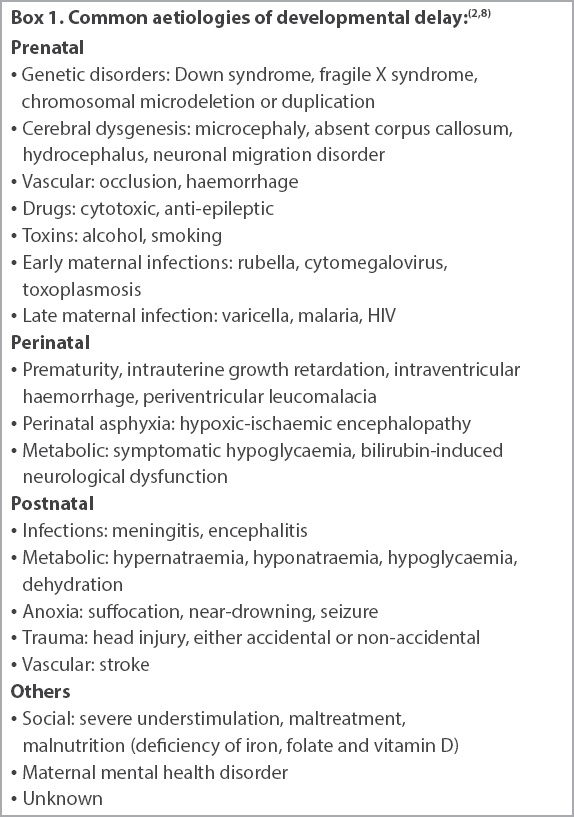

Multiple causes or illnesses can contribute to developmental delay. The causes listed in

Studies evaluating the causes of GDD have indicated that in one-third of the cases, the cause can be established through history and examination alone, and in another one-third, through a thorough clinical evaluation prompting investigations. The remaining cases can be identified through investigations alone.(9)

HOW DO I IDENTIFY DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY?

In primary care settings, children with developmental delays are normally identified through three major channels: during routine developmental surveillance or screening; following parental concern; and after third parties such as preschool teachers or nursery care professionals raise concerns. The child’s health booklet is a useful resource that should be wisely utilised by parents and clinicians to monitor a child’s development. An important step to improve the early identification of developmental delay is educating the parent to make use of the health booklet’s developmental checklist. Other details regarding developmental surveillance and screening have been discussed in our previous article on developmental assessment.(10)

Common barriers to early identification

Apart from the aforementioned barriers of lack of time, resources and training, the primary care physician’s referral to a specialist for further assessment and management may not be activated by the parent. This could be due to parents disagreeing with the referral, denial, lack of understanding of the significance of the referral or the family’s social circumstances (e.g. single parenthood, lack of financial resources), preventing the children from accessing further care.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

During each consultation, the primary care physician should encourage the parents to share any concerns they might have about their child’s development or behaviour, conduct an opportunistic evaluation (developmental surveillance) and ensure that the child has attended developmental screening at the prescribed touch points. Based on the consultation, a decision can be made to review again, refer further or discharge. For children presenting with mild developmental delay, in the absence of any red flags and no abnormality detected on clinical examination, parents can be advised about appropriate stimulation activities and a review conducted in three months’ time, especially if earlier milestones were achieved. For example, an 18-month-old child may present with concerns of expressive language delay, as he has only started saying a few single words with meaning. In the absence of any other concerns (e.g. the child has good eye contact and joint attention, with no behaviour concerns), advice on language stimulation activities could be given. In children presenting with significant developmental delays or with a history of regression in development, and those at risk for developmental delays, a prompt referral should be made to a developmental paediatrician.

In cases where delays have been identified, but there is parental denial, consider arranging a follow-up appointment to conduct a more detailed developmental assessment. The functional impact of the child’s developmental delay should be explained to the parents. For example, if a child is identified with a fine motor delay, the possible impact on adaptive skills should be explored. When a consultation is pitched at the parental level of understanding, there is a better chance of acceptance. A lower referral threshold is advisable for children who are at high risk for developmental problems, such as preterm children (without follow-up), children with chronic medical conditions, and children in challenging circumstances (e.g. being in the care system or having a main caregiver with mental health problems). Primary care physicians should follow up with the parents at the next visit to ensure that the referral has been activated.

Furthermore, consistent long-term emotional and practical support should be provided to the families of children with special needs. As this group is at high risk for caregiver stress, consider evaluating stress levels at each opportunistic visit, as well-being has an impact on their capability to look after their children.(11) The family can be referred to a Family Service Centre for further support if necessary. Other assessments and investigations include:

Head-to-toe examination, including plotting the child’s weight, height and occipitofrontal circumference;

Hearing assessment if there are concerns about hearing (e.g. poor response to name when called) and language delay;

Vision assessment if the child (≥ 6 weeks) is not fixing and following, has a history of frequent bumping into objects (for a mobile child), or may have delayed fine motor skills; and

Full blood count (possible iron deficiency), bone mineral profile and vitamin D levels (if rickets are suggested), thyroid function tests (especially for children with GDD and growth problems), urea levels and electrolyte levels.

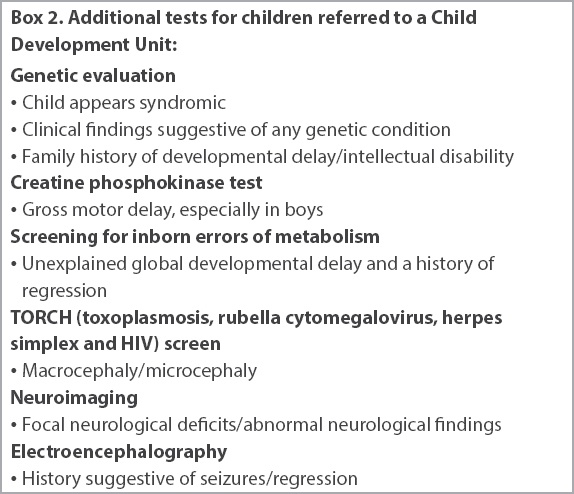

For preschoolers in Singapore, the two main Child Developmental Units (CDUs) are the Department of Child Development at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and the Child Development Unit at National University Hospital. If a child is referred to a CDU, a developmental assessment is conducted, and investigations are tailored based on the clinical evaluation. Apart from the aforementioned tests, these could include: genetic evaluation; creatine phosphokinase test; screening for inborn errors of metabolism; TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex and HIV) screen; neuroimaging; and electroencephalography (

Box 2

Additional tests for children referred to a Child Development Unit

Services for children presenting with developmental delays

Following further specialist assessment, children can be referred to appropriate therapies, such as speech language therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and behavioural intervention (e.g. psychologist). Children who could benefit from intensive and long-term interventions, such as those presenting with GDD, are referred to EIPIC (Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children) centres during their preschool years. Some children with developmental delays may require cognitive testing (e.g. IQ testing) and assessment of adaptive functioning at about six years of age. This would guide appropriate school placement if they are deemed more suitable for a special education school. Children in mainstream schools who continue to present with developmental delays may need ongoing therapy services provided in a hospital or private setting.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Developmental delays are common and can involve either a single domain or multiple domains of the child’s functioning.

-

Early identification of developmental delays and appropriate management can positively alter the child’s developmental trajectory.

-

Primary care physicians play a pivotal role in early identification of developmental delays through developmental screening and surveillance.

-

For children presenting with mild developmental delays and in the absence of any red flags, appropriate stimulation activities can be suggested, with close monitoring of the child.

-

There should be a low threshold for specialist referral for children at high risk for developmental problems, such as those who are in care, have an underlying chronic medical condition, or have a primary caregiver with a mental health problem.

You obtained more relevant history from Jason's mother. She said he was full term and had an uneventful neonatal period. Jason had passed his newborn hearing test and developmental screening at the previous touch points. He had never been hospitalised or exposed to any ototoxic agents, and had no history of any significant infections such as meningitis. You explained that Jason's expressive language seemed to be delayed. At three ye rs of age, he should be able to speak in three- to four-word sentences and have speech that is intelligible to trangers. Because of the expressive language delay, you recommended a referral to a Child Developmental Unit for a hearing assessment as well as further evaluation of speech and language.

SMJ-60-123.pdf