Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We aimed to examine the relative importance of medical and psychosocial needs of Asian breast cancer patients and their caregivers, and to identify the determinants of quality of life (QoL) at the time of diagnosis.

METHODS

This is a prospective observational study of the perceived needs and QoL of 99 dyads of breast cancer patients and their caregivers at diagnosis. A self-administered questionnaire was used to measure the perceived importance of medical and psychosocial support needs. Short Form-36 health survey (SF-36) version 2 was used to measure QoL. We also collected patient and caregiver demographic profiles and disease-specific information. Descriptive analysis of perceived needs was performed. SF-36 scores for eight domains and composite scores were calculated. Bivariate analysis and linear regression were performed to identify significant independent predictors of QoL of patients and caregivers.

RESULTS

The mean ages of the patients and caregivers were 56.5 years and 51.7 years, respectively. To have family around (73%), prompt information about treatment and treatment options, including side effects (71%), and prompt treatment for side effects (71%) were the top three needs among patients and their caregivers. Supportive nurses and prompt treatment for side effects positively improved patients’ social functioning and bodily pain scores. Stage of disease, age, education and ethnicity also influenced QoL. Only the presence of chronic disease influenced caregivers’ physical functioning and role-physical scores.

CONCLUSION

Patients and caregivers have similar perceptions of needs at diagnosis. A supportive healthcare team can positively influence patients’ QoL, highlighting the importance of tailoring support according to needs.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women internationally. An estimated 1.7 million female breast cancer cases were diagnosed in 2012,(1) with 24% diagnosed in Asia.(2) Singapore has the highest breast cancer incidence rate in Southeast Asia(2) and it has been on the rise in the last 35 years, with an age-standardised incidence rate of 21.5 per 100,000 in 1970–1975 and tripling to 61.9 per 100,000 in 2011–2015. With more than 9,600 women diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011–2015 in Singapore,(3) there is a need to better understand the needs and quality of life (QoL) of breast cancer patients and their supporting caregivers in order to better organise support for them during the course of treatment. This will improve not only their QoL, but also their survival rates. Research has shown that a breast cancer diagnosis and the treatment trajectory(4-7) can have negative psychological impact on both patients and their caregivers. Caregivers’ anxiety levels have been found to influence the women’s well-being.(8) Reported unmet supportive care needs have been observed to be significantly associated with poorer QoL among breast cancer patients,(9,10) which could potentially impact long-term survival.(11) At the same time, cultural differences in supportive care needs have been reported among breast cancer patients of different cultural origins.(12-14) Changes in body image as a result of breast cancer surgery have also been found to impact QoL among patients.(15)

Research into the needs of caregivers of women with breast cancer is lacking, particularly in the Asian setting.(5,16-18) Studies have found that information needs are important to male partners in facilitating their ability to care for their wives at the time of diagnosis, while others have focused specifically on the impact of post-mastectomy changes in body image on partners. Studies that examined the QoL of caregivers have found that patients’ QoL, disease factors and social factors (such as perceived adequacy of social support) influence the QoL of caregivers.(19,20) We hypothesised that, based on the differences in cultural background, the needs of Asian patients and caregivers would be different from those of the Caucasian population.

A Breast Health Global Initiative 2013 consensus statement was released to guide resource allocation for supportive care.(21) However, no studies have so far specifically examined the relative importance of the various supportive needs of breast cancer patients and their caregivers, as well as the impact of supportive care on their QoL, to guide healthcare professionals in the prioritisation, design and delivery of supportive care to patients and their caregivers during the treatment of breast cancer.

Therefore, we sought to examine the level of importance of supportive needs of Asian breast cancer patients and their caregivers in the following domains: diagnosis and treatment support; personal and emotional support; femininity and body image; and support of family and friends, during initial treatment. We also studied the effects of such support on their QoL at the time of diagnosis.

METHODS

This is a prospective, longitudinal observational study of dyads of patients and their nominated caregivers. The patients were diagnosed with breast cancer and treated at a 1,000-bedded regional hospital that serves a community of 1.4 million residents in the eastern part of Singapore.(22) Singapore is a multi-ethnic island state comprising a population of about four million residents who are predominantly Chinese (74.3%).(23) From 2009 to 2012, all consecutive patients who were ≥ 21 years old, female and not pregnant at the time of diagnosis were invited to participate in this study together with a nominated caregiver. All participants were given the option to withdraw from the study at any point in time.

The study was designed to examine the needs of patients and their caregivers, as well as their QoL over a period of 12 months at the following defined time-points: (a) T0: up to six weeks after diagnosis of breast cancer; (b) T1: three months after diagnosis while the patient was undergoing the initial phase of adjuvant therapy; (c) T2: six months after diagnosis when the patient had recently completed adjuvant chemotherapy and had stable disease; and (d) T3: 12 months after diagnosis when the patient was stable and might or might not be experiencing a recurrence. Analysis on the relative importance of the types of supportive needs of breast cancer patients and their caregivers was based on the results at T0.

A caregiver was defined as an individual nominated by the patient who played a significant role in providing support to the patient in the course of her treatment of breast cancer. The caregiver could be a spouse, life partner, child, family member or friend.

A study-specific questionnaire was developed to examine the importance level of the needs of breast cancer patients and their caregivers based on the bio-psycho-social medical model, with reference to the Supportive Care Framework.(24) The Supportive Care Framework describes individuals with cancer and their family members who experience different needs across the different phases of the disease, including the diagnostic, treatment and follow-up phases, and how factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, culture, education, religion, coping resources and social support influence them.

Five domains of perceived needs were identified through a literature review,(5,6) and refined through the expert opinions of breast cancer surgeons and breast cancer nurses. The domains identified were: (a) supportive needs at the time of diagnosis; (b) supportive needs at the time of treatment; (c) personal and emotional support; (d) support on issues regarding femininity and body image; and (e) support of family. Face validity and readability of the questionnaire was examined via focus group discussion with breast cancer patients who were at different stages of treatment. No further domains were identified through the focus group discussion. Four specific questionnaires were developed to examine the level of importance of the perceived needs of the patients and their caregivers at diagnosis (T0) and during treatment (T1, T2 and T3). Only the results of the questionnaire that focused on needs at diagnosis (T0) were analysed for this paper.

The Short Form-36 health survey version 2 (SF-36v2) comprises eight health domains: physical functioning (PF); role-physical (RP); bodily pain (BP); general health (GH); vitality (VT); social functioning (SF); role-emotional (RE); and mental health (MH). Higher scores reflect better perceived health. From these, two summary scores, the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS), were derived.(25) Both the English and Chinese versions of the SF-36v2 have been validated for use in Singapore by another study.(26)

All consecutive female patients aged ≥ 21 years with newly diagnosed unilateral breast cancer were invited to participate in the study by a trained research nurse who was not part of the healthcare team managing the patient. Patients who agreed to participate in the study were asked to nominate a caregiver to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from both the patient and her caregiver. Patients who were pregnant at the time of diagnosis, had malignant phyllodes cancer, or had cognitive impairment that prevented them from completing the surveys were excluded. Out of 182 patients who presented to the hospital in 2009–2012, 178 (97.8%) patients agreed to participate, and 116 (98.3%) out of 118 caregivers were recruited. A total of 99 dyads of patients (55.6%) and caregivers (85.3%) completed the survey prior to surgery and had complete data at T0 for analysis. Survey instruments were self-administered with the option of assistance by a trained research nurse when the participants had any queries regarding the instruments.

Data was tabulated and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis was performed for sociodemographic data, disease characteristics and level of importance of perceived needs. Importance of types of needs for patients and caregivers was analysed separately. Separate multivariable regression models were run to identify factors influencing the QoL of patients and caregivers. The responses ‘Extremely important’ to ‘Not important’ on the Likert scale were re-categorised. For the regression models, ‘Extremely important’, ‘Important’ and ‘Moderately important’ were categorised together as ‘Important’, while ‘Not important’ and ‘Not very important’ were categorised together as ‘Not important’. ‘Strongly agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’ responses on the Likert scale were also re-categorised. ‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Agree’ were categorised together as ‘Agree’, while ‘Neutral’, ‘Disagree’ and ‘Strongly disagree’ were categorised together as ‘Disagree’ for the regression models.

The validity of the questionnaire was tested using Pearson product-moment correlations, which was done by correlating each item questionnaire score with the total score. Item-item questionnaire score significantly correlated with the total score, thus indicating the validity of the items in the questionnaire. Reliability statistics were applied to the questionnaire for the patient and caregiver separately, and Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.84 (caregiver) and 0.88 (patient) were obtained, indicating the reliability of these questionnaires.

RESULTS

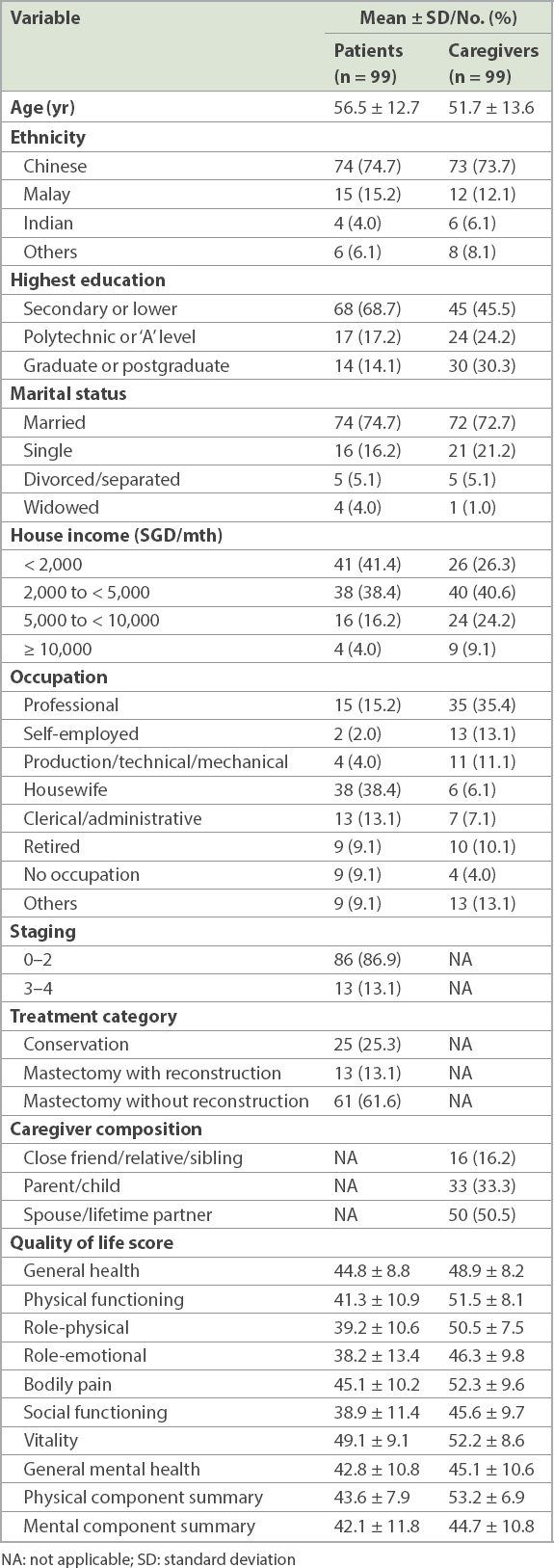

The mean age of the patients was 56.5 years, with the majority (74.7%) being married and having secondary or lower education (68.7%). 38.4% of the patients were housewives. About half (50.5%) of the nominated caregivers were spouses or life-time partners, while 33.3% were parents or children (

Table I

Profile and quality of life scores of patients and caregivers.

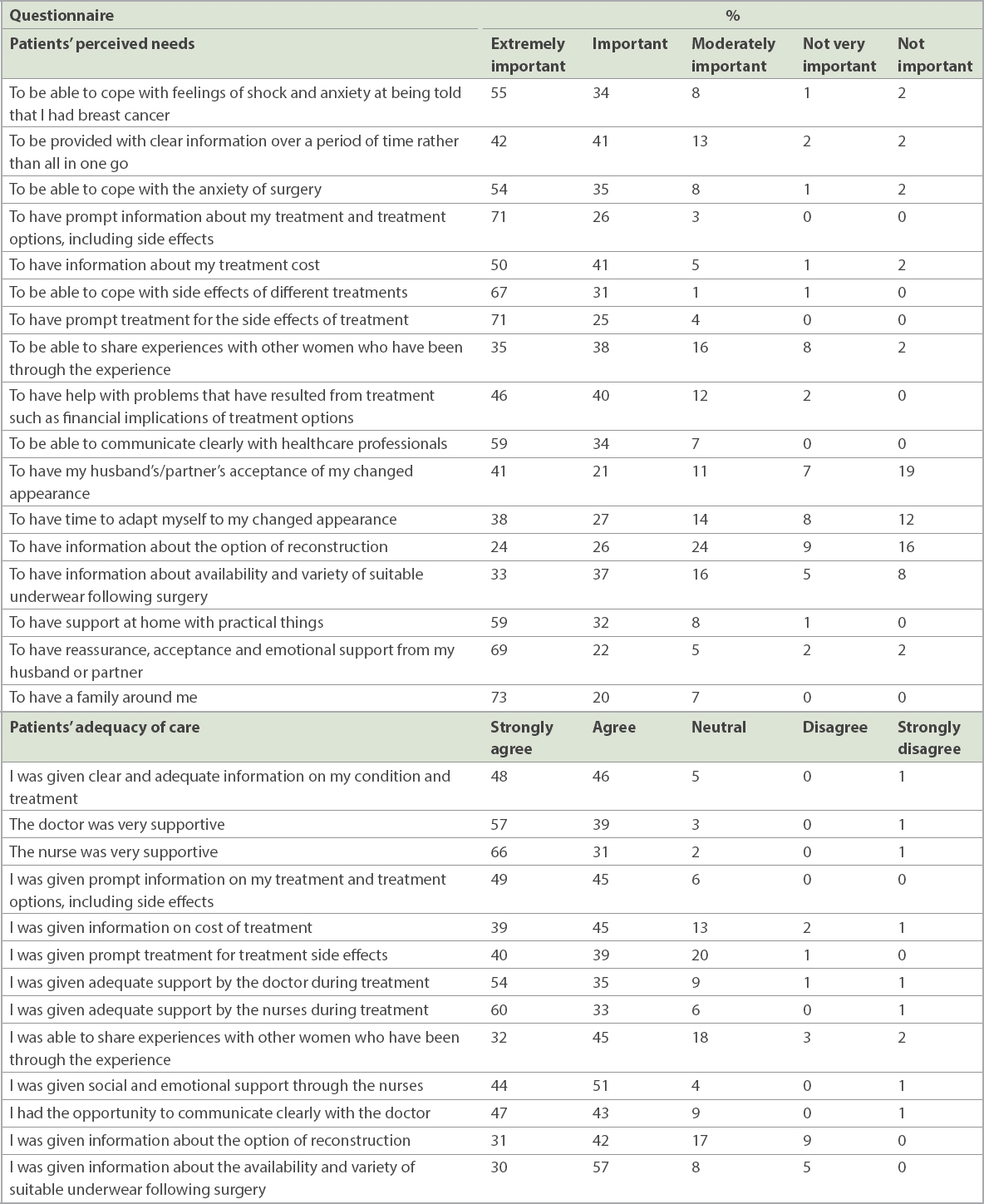

To have family around oneself (73%), prompt information about treatment and treatment options, including side effects (71%), and prompt treatment for side effects of treatment (71%) were the top three needs that most patients rated as extremely important at the point of diagnosis. Fewer patients (24%–41%) rated needs surrounding femininity and body image as extremely important. More than 90% of patients strongly agreed or agreed that doctors and nurses were supportive and provided adequate support during treatment (

Table II

Patients’ perceived needs and adequacy of care.

Most caregivers felt that it was extremely important to be provided with prompt information (80%) and for prompt treatment to be given to their partners (74%). Having family around oneself (65%) was among the top three needs of caregivers. Similarly, fewer caregivers (< 30%) reported needs surrounding femininity and body image as extremely important. More than 90% of caregivers agreed that adequate information was given on their partner’s condition and treatment, and that doctors and nurses were supportive. However, only 78% of them agreed that their partners were promptly treated for treatment side effects, and only 89% agreed that they received prompt information on their partner’s treatment and treatment options, including side effects (

Table III

Caregivers’ perceived needs and adequacy of care.

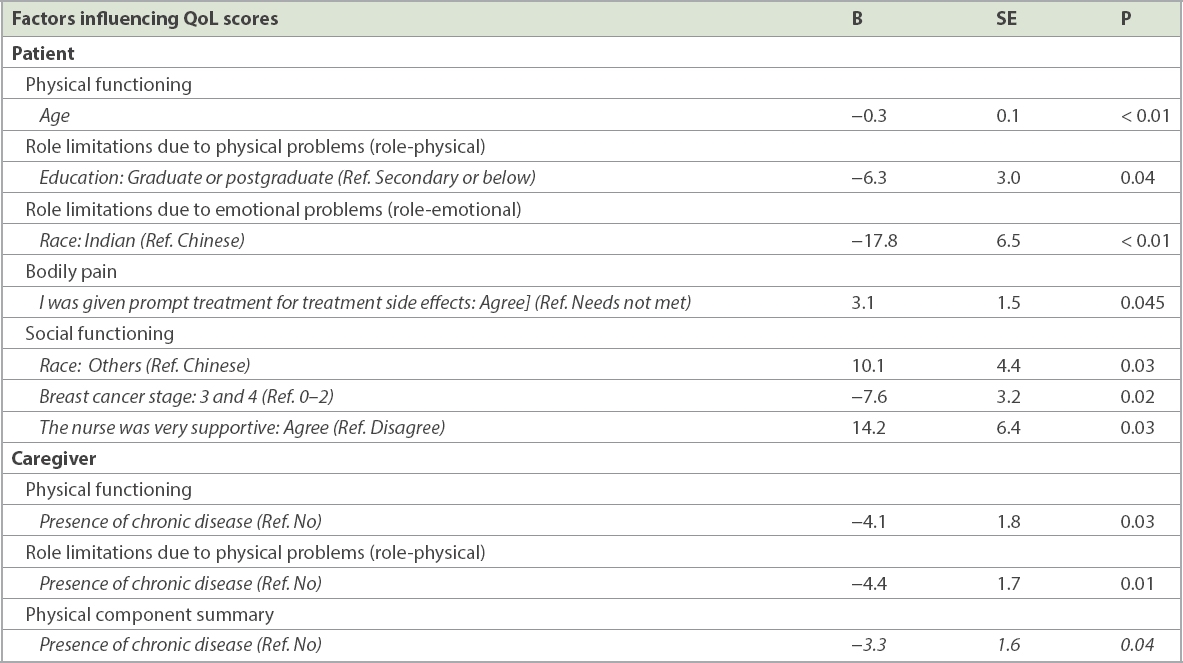

Scores for QoL were clinically significantly different between patients and caregivers in five domains, namely PF, RP, RE, BP and SF, with the greatest difference in the domain of RP (patient: 39.2 ± 10.6 vs. caregiver: 50.5 ± 7.5;

Table IV

Factors influencing quality of life (QoL) scores of patients and caregivers.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in a multi-ethnic Asian population that examined the levels of importance of needs among dyads of breast cancer patients and their caregivers, and the effects on their QoL. Family support, prompt treatment for side effects of treatment and prompt information on treatment were most frequently rated as extremely important among patients and caregivers during initial diagnosis and treatment. The greatest difference in QoL scores between patients and caregivers was in the RP domain. Having supportive nurses as part of the treatment team positively improved patients’ QoL in the RP and SF domains, but this was not so for caregivers. These findings highlight the importance of personalised support from the healthcare team during the initial treatment both for patients and their caregivers, addressing their need for improved QoL.

In a qualitative study of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in Norway, Landmark et al reported that the need for knowledge and psychosocial support in the initial phase were factors that influenced coping ability.(6) This is similar to the findings of our study, where the need for family support and prompt information on treatment side effects was perceived as extremely important among the majority of our Asian patients. However, the possible influence of cultural differences on supportive care needs remains. This was highlighted by Lam et al in a Hong Kong study, which found that fewer German women with breast cancer reported having unmet needs compared to Chinese women with breast cancer. While unmet needs in the health system and information domains were most prevalent among Chinese women, unmet needs in the psychological and sexuality domains were observed mostly among German women.(27)

To date, research into supportive needs has utilised the Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form Questionnaire, which measures the level of supportive needs. A study by Edib et al, conducted in 117 breast cancer survivors who were predominantly Malay, reported that the greatest support required was in the area of psychological needs pertaining to the feeling of not being in control (78.6%) and the fear of cancer spreading (76.1%). Conversely, the need for information on managing side effects at home (27.4%) and being adequately informed about the benefits and side effects of treatments (23.1%) ranked lower.(10) This contrasted with the results of our study, where having prompt treatment and prompt information on treatment side effects at diagnosis/initial treatment were important to our cohort of patients. This observation suggests that the needs of patients should be assessed at different stages of their disease and consistent with the Supportive Care Framework.(24)

Our study revealed that caregivers had similar perceptions as patients regarding the level of importance of different types of needs. However, most caregivers reported that prompt information on side effects of treatment and treatment options was more important (i.e. ‘extremely important’) than having family support, whereas most patients considered the latter to be extremely important. In a qualitative study by Cheng et al, male partners reported needing accurate and reliable medical and treatment-related information to help them support their partners.(18) This need for information by partners was also reported by other overseas researchers.(5)

While studies in the Western population have reported patients and spouses needing counselling on changes in the patient’s body image as a result of treatment,(17) the importance of receiving support in this area was perceived as extremely important in less than 40% of patients and 30% of caregivers in our population of Asian respondents. This could be due to the relative importance of information needs during the early stages of diagnosis and treatment among Asian patients, as reported by Lam et al’s subgroup analysis, which found that Hong Kong Chinese women prioritised the need for information about their disease and treatment, whereas German Caucasian women prioritised physical and psychological support.(27) In a qualitative study of 35 East Asian migrant women who underwent surgical treatment for breast cancer, Fu et al reported that the breast was deemed by these women as a function of their role as a wife or mother, thus eliminating the need for breasts when these roles have been fulfilled.(28)

The QoL of both patients and caregivers in our study was much lower than that of the general population across all domains of the SF-36v2, as reported by Thumboo et al.(26) The largest difference for patients and caregivers was in the domain of RP and the smallest was in the domain of MH. The impact on QoL among our patients was similar to that reported by Hanson Frost et al, where the greatest reduction from age-specific normed scores was for RP (RP −1.35 ± 1.12 vs. RE −0.43 ± 1.27) among their 35 newly diagnosed cancer patients. The impact on QoL among our caregivers was greatest in the MH domain (45.1 ± 10.5), with the smallest difference compared to that of the patients (MH 42.8 ± 10.8).(4) This suggests that the mental health of caregivers is closely related to that of the patients, which is consistent with Bergelt et al’s finding that higher mental health score of patients predicted higher mental health score of partners.(19)

We found that race, age, education level and stage of disease were significant factors influencing the QoL of patients. Older age and higher stage of disease had negative effect on PF and SF, respectively. Age has been reported to have both negative and positive impact on QoL.(29) The positive impact of low stage of cancer has also been consistently reported by researchers across different populations of breast cancer patients.(29-32) While Shen et al found that higher education increased QoL, our study showed that having a graduate or postgraduate education decreased QoL in the RP domain, when compared with having a secondary or below education level.(29)

More importantly, our study highlighted that having supportive nurses at the time of diagnosis could positively influence a patient’s SF. At the same time, providing prompt treatment for side effects to patients who felt that prompt treatment was important positively influenced BP. These findings reinforce the need for the healthcare team to better design supportive care for breast cancer patients. Although supportive nurses did not influence the QoL of caregivers, caregivers’ needs, particularly their need for information on treatment and side effects, should be addressed, as caregivers have reported these needs as extremely important during the time of diagnosis and early treatment.

There is limited research done in the area of understanding the QoL of caregivers of breast cancer patients, particularly at the time of diagnosis. A study examining the effect of social support on caregiver’s QoL found that the type of social support received, being retired and the type of relationship with the patient could negatively impact QoL.(20) Bergelt et al reported that higher mental QoL in breast cancer patients predicted higher physical and mental QoL among caregivers.(19) In our study, the only factor influencing patient QoL in the domains of GH and RP was the presence of chronic conditions. Therefore, more support could be considered for caregivers who have existing chronic diseases so as to reduce the negative impact on their QoL. Although a positive effect of having supportive nursing staff on patients’ QoL was reported, this was not observed among caregivers. This could have been influenced by the smaller proportion of caregivers who perceived that the nursing staff were supportive (caregiver: 96.2% vs. patient: 97.2%), as well as the small sample size.

This study was not without limitations. Our findings were based on a convenience sample of all consecutive dyads of patients and caregivers who were agreeable to participate in the study, and so they might not be representative of those who declined participation, or the general breast cancer patient and caregiver populations in Singapore. However, the ethnic distribution of our sampled population was representative of that reported in Singapore.(3) The influence of culture on the reluctance to discuss issues on femininity needs to be explored through further qualitative research to better understand the concerns surrounding changes in body image among the Asian population. Further research could also be conducted to better understand the types of support that patients and caregivers would like to receive, in order to better design the delivery of supportive care by healthcare providers at the time of diagnosis and early treatment.

In conclusion, the current study is the first to examine the importance of types of supportive needs of both breast cancer patients and their caregivers in a multi-ethnic Asian population, and the impact of these needs on their QoL at the time of diagnosis. Although both our patients and their caregivers placed similar importance on the types of support needed, most patients rated family support as being extremely important, while caregivers considered receiving prompt information on treatment and side effects at the time of diagnosis and early treatment to be extremely important. Therefore, it is vital to consider not only the stage of disease, but also differences in the type of needs of patients and their caregivers, so as to better tailor the delivery of supportive care to the individual patient and, in so doing, improve the QoL of both patients and their caregivers.