Abstract

Medical reports are required to support court applications to appoint a deputy to make decisions on behalf of a person who has lost mental capacity. The doctor writing such a medical report needs to be able to systematically assess the mental capacity of the person in question, in order to gather the necessary evidence for the court to make a decision. If the medical report is not adequate, the application will be rejected and the appointment of the deputy delayed. This article sets out best practices for performing the assessment and writing the medical report, common errors, and issues of concern.

INTRODUCTION

Objectives

This paper updates the reader on the need to certify the mental capacity of a person for various matters, in particular, to support a court application appointing a deputy for him/her; the legal requirements for a medical report supporting such an application; and how to assess mental capacity.

Appointment of donee(s)

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA), Singapore, allows persons with mental capacity to voluntarily make a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) appointing one or more persons, as donee(s), to make decisions on their behalf if and when they lose mental capacity. A donee may be appointed for matters relating to the person’s personal welfare, and/or his property and affairs.(1) With the exception of psychiatrists, all medical practitioners need to be accredited by the Public Guardian to be a ‘certificate issuer’ to certify that the person has the capacity to make the LPA. This can be done by attending a prescribed course, which is available online at the Singapore Medical Association’s website.(2)

Appointment of a deputy

In cases where an LPA was not made before the loss of mental capacity, the MCA allows a deputy to be appointed by the court to make decisions on behalf of the person (P).(3) A deputy can be appointed for matters regarding personal welfare, and/or property and affairs.(3) The individual applying to become P’s deputy is usually a relative or close friend.

Medical report required for deputy application

The court application to appoint a deputy (deputy application) must state whether the applicant wishes to be P’s deputy in terms of personal welfare, and/or property and affairs. It must be accompanied by a doctor’s affidavit exhibiting a medical report, which must state whether P lacks capacity either in relation to his personal welfare, or his property and affairs, or both (depending on what the court application requires). The court will rely on the medical report to decide whether P lacks mental capacity in any of the areas mentioned, which is a decision that must be made before a deputy can be appointed for P in that area. If the medical report is inadequate, the court will reject the deputy’s application.(4)

MEDICAL REPORT WRITING

Standard template – Form 224

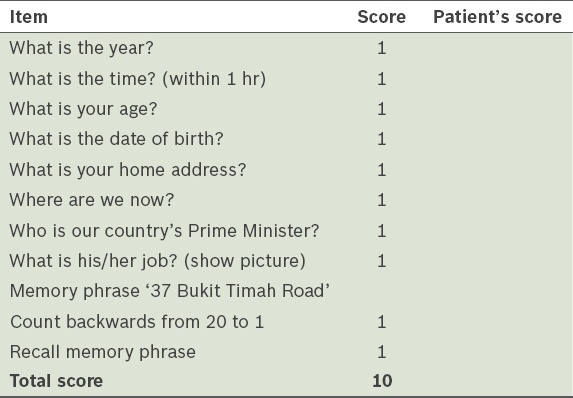

All medical reports for deputy applications must be in the standard template set out in Form 224 in the Family Justice Courts Practice Directions 2015.(5) There are five sections to the form (

Table I

Form 224 and the information required.

Areas to pay attention to

Lapse of time between date of last examination of P and date of report

The acceptable lapse of time between the date of the last examination of P and the date of the report depends on (a) how established the relationship between the doctor and P is; and (b) whether P’s condition is permanent or temporary (i.e. is there a possibility that P could recover from this state). Hence, it is necessary to state: (a) details of the doctor-patient relationship, i.e. how long the doctor has known P (e.g. the patient first came to see me in 2010); how regularly P has been seeing the doctor (e.g. the patient has come to me for regular follow-up 2–3 times a year in the past five years); the date of the doctor’s last examination of P; (b) whether P’s condition is permanent or temporary, and the reasons for this conclusion.

In cases where: (a) the doctor has only seen P once or twice (e.g. the doctor only saw P as an outpatient on one occasion and P then defaulted on follow-up), the acceptable lapse is about 2–3 months (subject to P’s condition); (b) P is seen regularly over a few years, a lapse of 5–7 months may still be acceptable (subject to P’s condition); (c) P’s condition is permanent (e.g. vascular dementia with profound dementia), even 7–8 months or a year’s lapse may be acceptable; and (d) P’s condition is not permanent (e.g. a head injury from a fall, but slowly recovering), then a lapse of not more than 3–6 months may be acceptable or, if P is in a vegetative state, the doctor should state whether this is a permanent condition (i.e. a persistent vegetative state).

Tests to establish P’s mental capacity

The doctor should give careful consideration as to the most appropriate test of mental capacity to administer to ascertain P’s mental capacity (see ‘Assessing mental capacity’). Additionally, it would be useful to ask questions related to P’s personal welfare, and/or property and affairs (see ‘Personal welfare and/or property and affairs-related questions’).

Evidence to support conclusions about P’s mental capacity

Conclusions (e.g. P could not understand simple questions; P made mistakes in simple math; P did not demonstrate understanding of information relating to more complex decisions such as those requiring a large sum of money or entering into a contract, etc) need to be supported by evidence (e.g. P answered ‘I don’t know’ when asked ‘What is your name?’; P could not subtract seven from ten; and P said ‘$10’, when asked how much his flat was worth). If the doctor administers a mental state test on P, he should not just provide a test score (e.g. Abbreviated Mental Test [AMT] score of 1/10), but recount what exactly was asked, detail what P’s answers were and explain the significance of the test score.

Avoiding unexplained medical jargon

The medical report is read by laypersons (i.e. lawyers and judges) and not just medical professionals. Technical medical terms in the report should be accompanied by explanations in simple English, or preferably, described in plain English (e.g. ‘perseveration’ could be replaced with ‘P had the habit of repeating the same word many times when answering a question’; the AMT score could be explained by ‘P had an AMT score of 1/10, which suggests severe impairment in P’s cognitive ability’; and ‘dysphasic’ can be explained as ‘a speech disorder which impairs P’s ability to speak and understand language’).

Check before signing off

As it is difficult to retract a medical report that has been signed and sent off, it is important to read the report carefully before signing it to sieve out any grammatical and spelling errors, and ensure that it: (a) flows smoothly; (b) makes sense and is logical; (c) is clear and concise; (d) is complete; and (e) does not contain any factual errors. If possible, a more experienced, senior colleague should review the report.

ASSESSING MENTAL CAPACITY

This section sets out the practical questions that a doctor should ask when assessing mental capacity in everyday clinical practice.

What is the ‘trigger’ for assessing P’s mental capacity?

Some possible scenarios:

- P’s significant other suspects that P has a mental capacity deficit, but P needs to make decisions and sign documents. If P lacks mental capacity, then a deputy application must be made.

- P wants to make an LPA.

- Other matters (e.g. P wants to draft a will.)

In each scenario, it would be useful to find out more about the ‘trigger’ (e.g. Does P need to give consent for an operation? Is his property slated for an en bloc sale soon?).

How to assess mental capacity

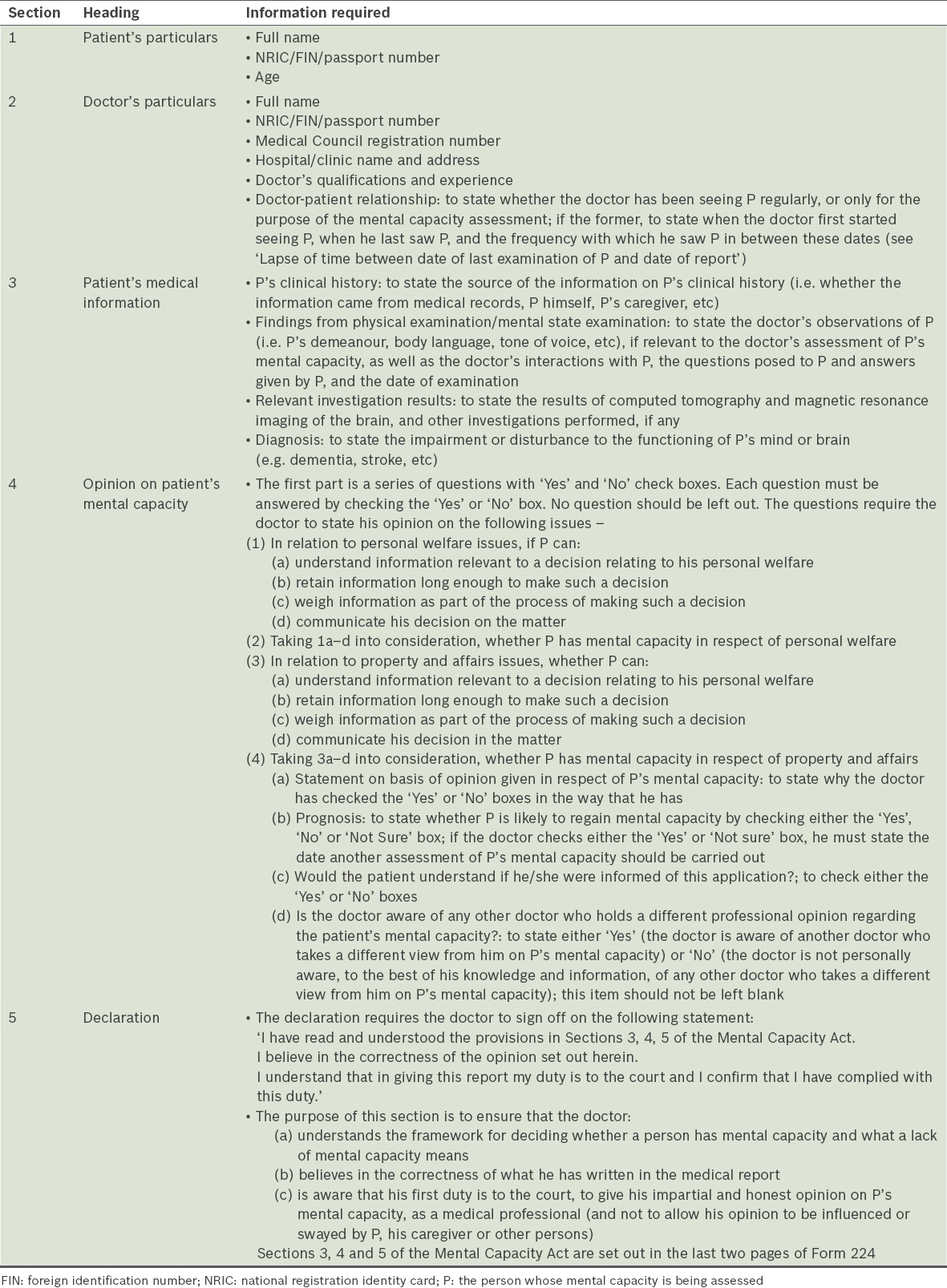

Section 4(1) of the MCA defines a person who is considered to lack mental capacity in relation to a matter; i.e. if, at the material time, he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain. A person is considered unable to make a decision for himself if he is unable to understand, retain or weigh information relevant to that decision, or to communicate his decision by any means, according to Section 5(1). Thus, the doctor doing the mental capacity assessment has, as a first step, to ascertain whether P has an impairment of, or a disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain. This is essentially a clinical assessment. As a second step, the doctor has to ascertain whether this condition, if it is present, has rendered P unable to make a decision in one or more matters, and what these matters are.

Checklist

Table II

Lack of mental capacity and a checklist on its assessment.

History

The doctor first needs to take an adequate history from a reliable informant and to supplement this with history from P, where possible. He should also review all past medical records, reports, hospital discharge summaries and other relevant documents when determining whether there is sufficient evidence for the first step of the MCA test (i.e. whether P has an impairment of, or a disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain).

Clinical examination

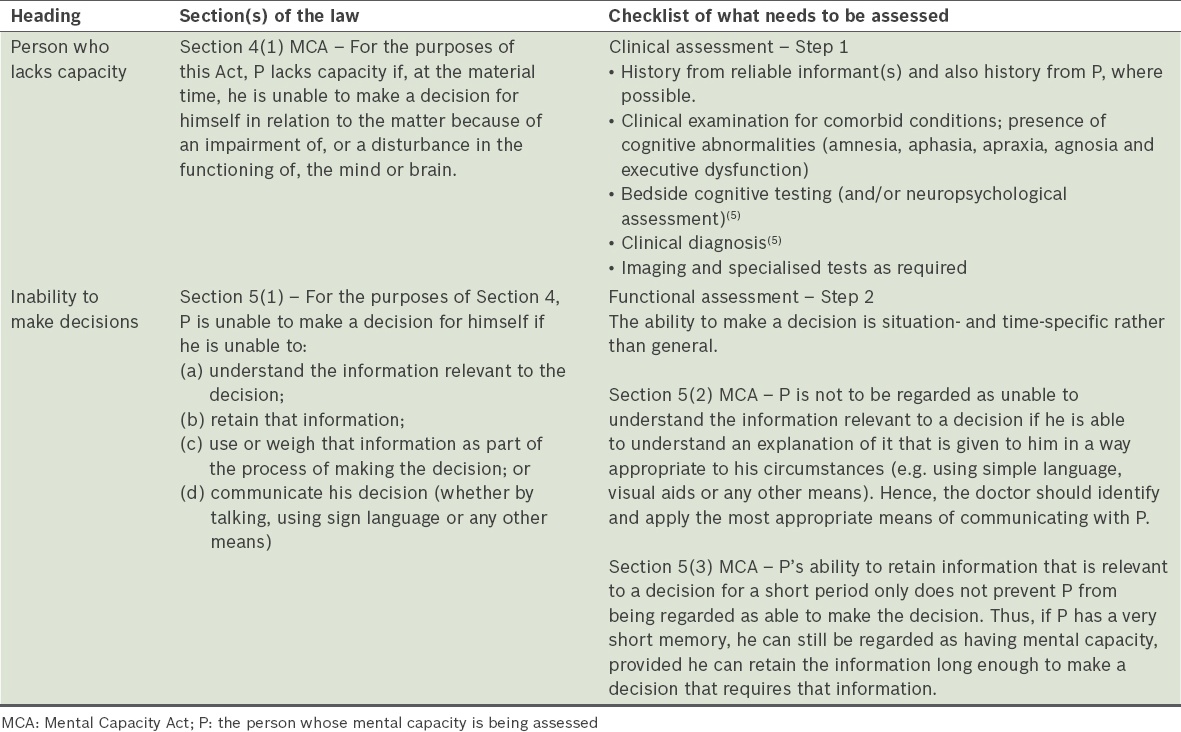

A clinical examination should follow the history-taking and include an assessment for the presence of cognitive abnormalities, as shown in

Box 1

Assessment for the presence of cognitive abnormalities:

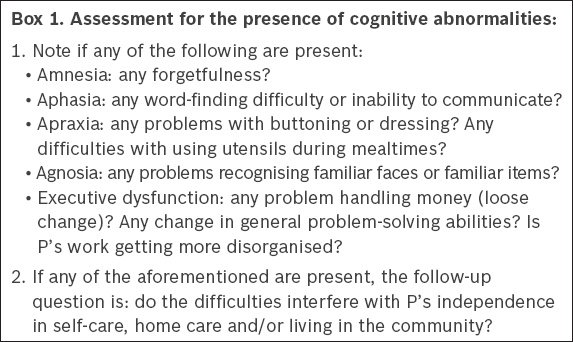

Bedside cognitive testing

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis by Tsoi et al(7) described 11 currently available screening tests for cognitive function (see ‘Staging dementia’ for more information on these screening tests). Common screening tests used in Singapore are the AMT, which consists of ten questions,(8) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which consists of 30 questions.

If P does not pass the AMT (or other similar tests), a further assessment must be performed to determine whether the cause is a medical problem and, if so, what this medical problem is (e.g. P had a stroke causing vascular dementia, which impairs/disturbs the functioning of his brain). If P fails the AMT or other similar tests for mental capacity and there is insufficient information to determine whether P has impairment or disturbance of brain or mind, then a referral to a relevant medical specialist (psychiatrist, neurologist or geriatrician) should be made to confirm the medical condition that resulted in the failure of the tests.

Next, the doctor should ask P questions relating to his personal welfare, and/or property and affairs (depending on the scope of the deputy application or LPA, as the case may be) in order to determine the matters in which P can make decisions. It is useful to shape the questions around the ‘trigger’ event.

Personal welfare and/or property and affairs-related questions

Questions that should be asked include: (a) whether P is aware of what medical conditions he has, what treatment he is receiving, what treatment he would like to receive or continue receiving and why; and (b) if P has property, what he wishes to do with it (e.g. sell it, rent it out or keep it empty; how much to sell it or rent it out for) and why. If the person has mental capacity and has not appointed a donee, it may be opportune for the physician to suggest that he consider doing so.

What stage of dementia severity is P at now?

The most common impairment or disturbance of the mind or brain on presentation is dementia. Hence, it is preferable for doctors performing the mental capacity assessment and writing reports to be familiar with the various stages of dementia. The severity of dementia determines the extent of P’s mental capacity impairment. Hence, some staging will be useful as a baseline; over time, further assessments can be performed to follow up on the progress of dementia. Cognitive impairment can range from normal ageing, to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), to dementia (mild to severe).

Comparing normal ageing and mild cognitive impairment

Normal ageing and MCI are both accompanied by a decline of cognitive functions with no significant impairment to daily life. In normal ageing, the body and brain slow down, but intelligence remains stable. Hence, more time is taken to process information and memory changes occur, such that it is common to have greater difficulty in remembering names of places, people and things. MCI differs from normal ageing in that memory problems are severe enough to be noticeable to other people and show up on tests of mental function, but are not severe enough to interfere significantly with daily life.

Progression

MCI is a transition period between normal ageing and dementia, and converts to Alzheimer’s Disease at an annual rate of 5%–15% as compared to normal ageing (1%).(11) Small decreases in the conversion rate of MCI to dementia might significantly reduce the prevalence of dementia. Crucially, studies have found that some cognitive brain networks are disrupted in ageing and MCI populations, and that physical activity can effectively remediate the function of these brain networks. Known predictors of progression of MCI include: older age, male gender, lower levels of physical activity and a higher Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score.(12) In an Italian study of 2,386 individuals with eight years of follow-up, the eight-year incidence of dementia (per 1,000 person-years) was 12.69 in the total sample, 9.86 in subjects with normal cognition at baseline, 22.99 in individuals with cognitive impairment but no dementia, and 21.43 in individuals with MCI.(13) Impairment to instrumental activities of daily living was found to be a predictor of progression to dementia.(13)

Staging dementia

Dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease) is characterised by progressive loss of memory and other intellectual abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life. Being able to stage the severity of dementia at the beginning of the illness and follow through with staging at different intervals is important from both the legal and medical points of view. There are three commonly used overall assessment tools: the MMSE, Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) and CDR scale.

The MMSE, also known as the Folstein test, has 30 questions. It is currently the most commonly used tool for cognitive impairment screening due to its simplicity, although the deficiencies of this test threaten its current popularity, namely the limited ability of the MMSE to detect cognitive impairment, its lack of suitability for illiterate subjects and high cost due to its copyright. Newer instruments with greater diagnostic accuracy for detecting cognitive impairment and dementia are now available.(14)

Some adjustments to the MMSE English version for use in Singapore are necessary:

-

Since Singapore has no distinct season changes – spring, summer, autumn or winter – there is a need to modify Question 5 of the standard MMSE (‘What is this season?’). It is suggested that a modification of the question to ‘What is the upcoming festival?’ is probably better than the change suggested by Feng et al,(15) namely ‘Without looking at your watch, what time is it?’, as it is not uncommon for people without cognitive impairment to be confused about time, especially if they do not lead a very structured day. However, the patient’s religious and cultural background should be evaluated before deciding which modification of the question should be used; for example, a Chinese person would probably be more aware of when Chinese New Year is compared to Deepavali.

-

Consequent to the small geography and territory of Singapore, there is a need to modify the following questions: (a) where are we now?; (b) state? (Question 6); country? (Question 7); town/city? (Question 8); hospital? (Question 9); and floor? (Question 10). Suggested changes to the questions are: (a) where are we now?; (b) country? (Question 6); which part of Singapore – North, South, East or West? (Question 7); which neighbourhood, e.g., Yishun, Toa Payoh, Hougang, Tiong Bahru? (Question 8); hospital? (Question 9); floor? (Question 10).

-

For ease of word pronunciation, in immediate recall (Questions 11–13) and delayed recall (Questions 19–21), Feng et al(15) changed the English version objects of ‘ball’, ‘flag’ and ‘tree’, which are single-syllable words, to ‘lemon’, ‘key’ and ‘balloon’ in the Chinese version, which are two-syllable words. This is a reasonable change, which we support.

-

For sentence repetition, Feng et al (14) changed ‘no ifs, ands or buts’, in Q24 of the English version, to ’44 stone lions’, which is a tongue twister when spoken in Mandarin. Ng et al (16) used this in their research, as well as ‘marah (angry, furious), merah (red), and murah (cheap)’ for the Malay version. We also support these changes to the English version of the MMSE when used in Singapore on persons whose primary language is Mandarin or Malay, respectively.

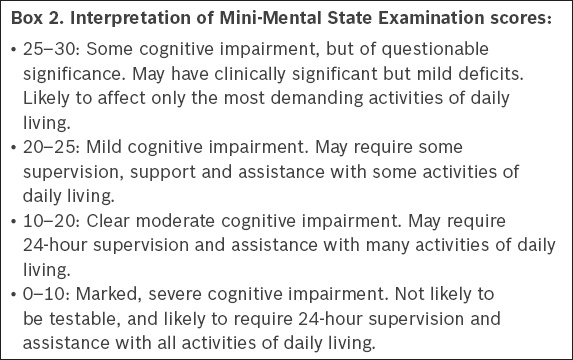

Box 2

Interpretation of Mini-Mental State Examination scores:

The GDS, which is used for overall staging of dementia into one of its seven stages, takes two minutes to complete once the relevant clinical information has been collated.(18) It is used to classify cases by severity in research or service development, but is not often used in Singapore. The CDR scale(19) allows more reliable staging of dementia than the MMSE, and is based on caregiver accounts of problems in daily functional and cognitive tasks. This scale is commonly used in Singapore. A copy of the CDR assessment form by Morris(20) is available online.(21) The CDR scale consists of five stages, namely: (a) Stage 1 – CDR-0 or no impairment; (b) Stage 2 – CDR-0.5 or questionable impairment; (c) Stage 3 – CDR-1 or mild impairment; (d) Stage 4 – CDR-2 or moderate impairment; (e) Stage 5 – CDR-3 or severe impairment. Each of these five stages evaluates the patient’s functioning in the following six areas: memory, orientation, judgment and problem-solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care

As P progresses along the stages, symptoms grow more severe. At Stage 1, P has no issues with memory, is well-adjusted at home and in the world at large, there is no damage to P’s ability to function, and he is fully aware of time and place. At Stage 2, P may exhibit slight difficulties, such as failing to handle timing well or to perform at full capacity in the workplace, but he is fully independent. At Stage 3, P may not be able to function independently in some areas of life; following directions and maintaining knowledge of time and place become problematic. At Stage 4, P needs significant help but can function autonomously in some settings. Short-term memory capacity is greatly reduced, and P is likely to be highly disoriented. At Stage 5, P is completely dependent on others, suffers significant damage to memory and usually shows very little understanding of the world around him.

CONCLUSION

Medical practitioners need to familiarise themselves with the template for medical reports (Form 224) for deputy applications, the legal requirements for such reports, and build skills and confidence in the assessment of mental capacity in accordance with the MCA framework.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr Colin Tan, District Judge, for his comments on the early draft of the portion of this article pertaining to medical report writing and to Ms Tan Rou’en, Assistant Director, Legal Aid Bureau, Singapore, for her help with the article. However, any errors and views expressed are entirely the authors’ own. In particular, they do not represent the views of the Legal Aid Bureau, Ministry of Law or Family Justice Courts, Singapore.