Abstract

Scabies is a common infestation worldwide, affecting persons of any age and socioeconomic status. In Singapore, it is more common in institutions rather than in homes. The two variants are classic scabies and crusted scabies, with the latter having a significantly higher mite burden. Early identification, isolation of index patients and prophylactic treatment of contacts are essential in dealing with the outbreak. Locally, most primary care practitioners make the diagnosis based on visual inspection and clinical examination. A skin scrape is done to confirm the diagnosis, especially in atypical presentations. Scabietic mites, eggs or faeces can be seen on microscopy. The usual treatment for adult scabies in Singapore is the use of topical malathion or permethrin. A combination of topical permethrin and oral ivermectin is used for crusted scabies.

Mdm Lee, who was alert and communicative, was wheeled into your consultation room for follow-up of hypertension. She had come from a nursing home and was accompanied by her daughter and a nurse from the home. While manually checking her blood pressure, you noticed that Mdm Lee was scratching incessantly. You examined her and noted numerous excoriated erythematous papules on the hands (palms and fingers), wrists, external genitalia and axillae. Mdm Lee said that she had felt increasingly itchy over the past week and had difficulty sleeping at night despite taking loratadine once daily. No new chronic medication had been prescribed to her in the past six months, according to the daughter and nurse. On questioning, the nurse said that none of the patients or staff in the ward had a similar rash. You made a provisional diagnosis of classic scabies and considered your next steps.

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

Scabies is a common infection affecting individuals of any age and socioeconomic status. The worldwide prevalence is estimated to be 100 million people.(1) Lim et al conducted a review of 114 patients who were treated for scabies at the National Skin Centre in 1982–1989.(2) The data showed that with increased modernisation in Singapore, the prevalence of scabies was higher in institutions such as intermediate and long-term care facilities rather than in residential homes. The authors postulated that this was because of improvements in housing facilities, resulting in less crowding. With the increase in travel and humanitarian work by our local population, particularly in developing countries, the risk of contracting scabies from people living in compromised housing has correspondingly increased.(3)

Clinical manifestations

The two major clinical variants of scabies are classic scabies and crusted scabies. Symptoms typically appear 2–6 weeks after infestation. Classic scabies (

Fig. 1

Photograph shows numerous erythematous papules on (a) the fingers and web spaces and (b) axilla of a patient with classic scabies.

Fig. 2

Photograph shows hyperkeratotic crusts on the fingers and palms in a nursing home patient with crusted scabies.

The salient features of classic scabies are intense itch, erythematous papules and excoriations, typical distribution, and a contact history of patients with scabies. The usual distribution is: the interdigital web space of the fingers, the insides of wrists and on the inner elbow; the soles of the feet; around the breasts and axillae; the male genitalia, especially the scrotal and penile areas; and on the buttocks, knees and shoulder blades.(6) In children, common sites of infestation are the scalp, face and neck, and palms and soles.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

Making the diagnosis

The combination of visual inspection, noting the characteristic pruritic lesions and their distribution, together with contact history enables the primary care practitioners to make a confident diagnosis of scabies. Differential diagnoses include other pruritic conditions such as drug eruptions, eczema, lichen planus and other infestations such as hemiptera (bedbugs). Apart from the symptomatology, other salient points in history-taking include a detailed drug history. Eczema may present at the flexures, while classical lichen planus tends to affect the volar aspects of wrists and ankles as well as the anterior aspects of the knees. As for scabies, areas affected include the interdigital web space of the fingers and the sides of the hands. The wrists, elbows, axillae, groin, breasts and feet are the other commonly affected sites (

Fig. 3

Photomicrograph of an adult Sarcoptes scabiei.

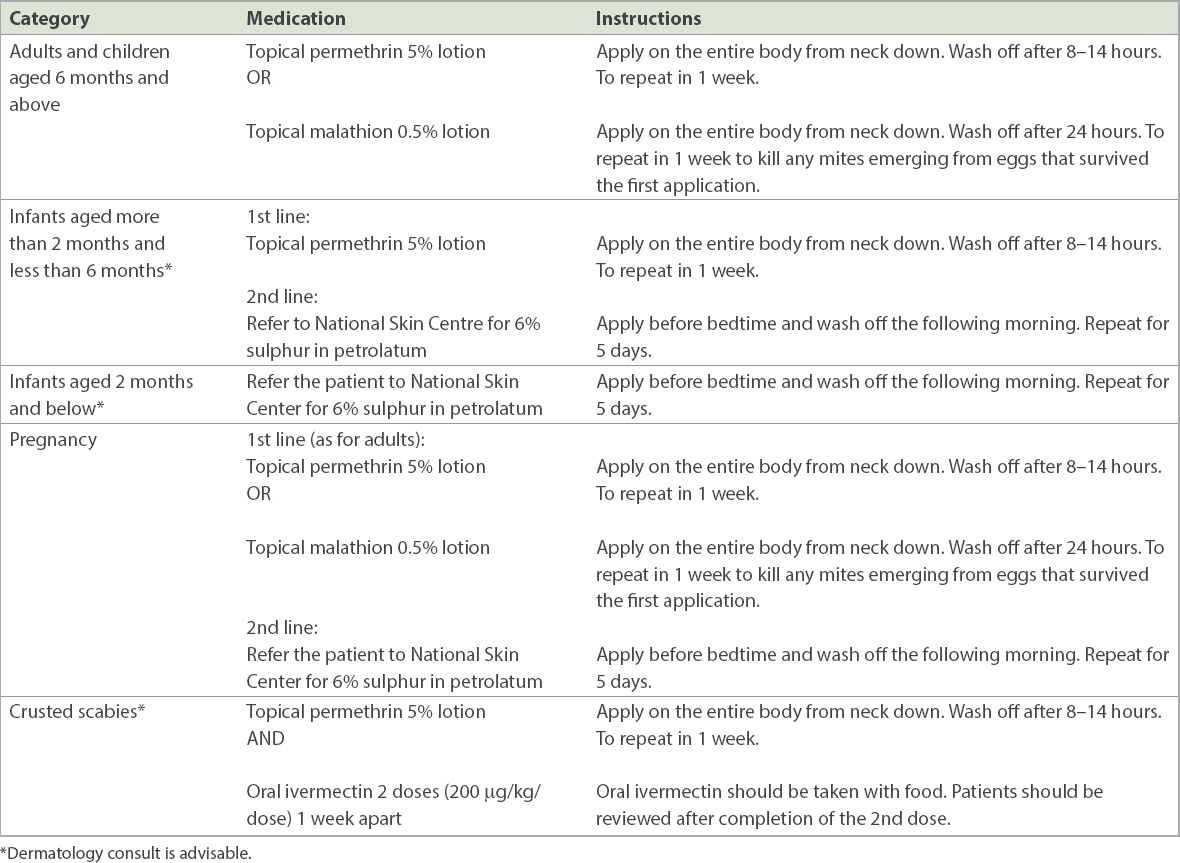

Early recognition and treatment

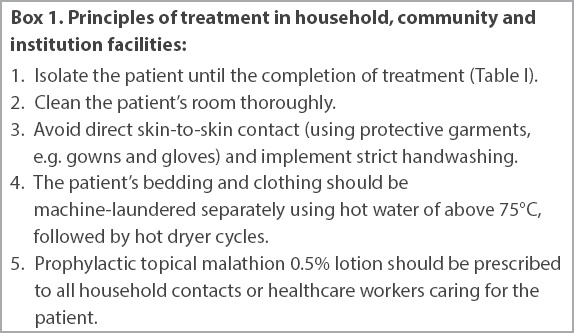

When asking a patient about number of household members, physicians are reminded to specifically ask if there were domestic helpers or grandparents living together or staying intermittently up to six weeks prior to the presentation. Patient and family members should be informed that although scabies infestation is relatively benign, it is highly transmissible. Therefore, the principles of treatment (

Box 1

Principles of treatment in household, community and institution facilities:

In nursing homes and institutions, early recognition of crusted scabies is essential to prevent outbreaks.(9) Once an outbreak occurs, prompt control of the index patient and rapid tracing of contacts to identify secondary cases are necessary. When prolonged exposure to a case of crusted scabies results in multiple secondary cases, the most efficient strategy for terminating the outbreak is the institution of simultaneous mass prophylaxis, which can be implemented without ward closure.

It is important to recognise that itching may persist or even worsen for some time after applying the medication. These steps may give patients some relief from itching:(10)

-

Cool and soak the skin by using a cool, wet washcloth on irritated areas of the skin.

-

Apply a soothing lotion such as calamine lotion.

-

If the itching is severe, consider antihistamines to relieve the itching and skin irritation. Non-sedative antihistamines appear to be as effective as sedating histamines.

-

After eradication of mites, medium-potency topical corticosteroids (in age-appropriate patients) can also be used to control itching for 1–2 weeks, especially for scabetic nodules.(5)

Scabies may result in secondary skin infections leading to boils, cellulitis or lymphangitis due to Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes). Streptococci and staphylococci have been isolated from skin burrows as well as mite faecal pellets, suggesting that the mites themselves may contribute to the spread of pathogenic bacteria.(11) Secondary infection of scabies with S. pyogenes is a major precipitant of acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and possibly rheumatic fever.(12)

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Scabies is a common infestation affecting individuals of any age and socioeconomic status.

-

In Singapore, scabies is more common in institutions than at home.

-

All household contacts of the patient need to be prophylactically treated and practise contact precautions.

-

Once an outbreak occurs, prompt control of the index patient and rapid tracing of contacts to identify secondary cases are necessary.

-

For adults, treatment for scabies comprises of two applications of topical malathion 0.5% or permethrin 5%, spaced one week apart.

-

For adults, the prophylaxis of scabies also comprises of two applications of topical malathion 0.5%, spaced one week apart, preferably both on the same days as the patient’s treatment.

-

It is advisable to refer patients with suspected crusted scabies to the dermatologist for further evaluation and management.

You treated Mdm Lee for suspected classic scabies and instituted contact precautions immediately. She was nursed in an isolation cubicle inside the nursing home. The chief nurse and management were informed of the outbreak. Mdm Lee’s linen, surroundings and bed were thoroughly washed and disinfected. Mdm Lee, along with the patients in the same cubicle and the nurses attending to her, were given two courses of malathion 0.5% lotion one week apart. Her daughter was also treated with an application of malathion 0.5% lotion one week apart, as she had been in close contact with her mother during her visits to the nursing home. By the end of the second week, Mdm Lee was feeling better and had no further evidence of scabies. No new cases of scabies were reported in the nursing home.

SMJ-60-285.pdf