Abstract

Dementia is a condition marked by the progressive and irreversible clinical syndrome of cognitive decline that is eventually severe enough to interfere with daily living. Management of dementia is often complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach. This article discusses the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as agitation, insomnia, restlessness, hallucinations, anxiety and depressed mood, for which patients and their caregivers commonly seek medical advice from their primary care clinician. These symptoms can cause significant distress to patients, their families and caregivers, and may even lead to the patient being prematurely institutionalised. Management consists of assessment of BPSD and supporting the needs of the family, especially those of the caregiver, and can be both non-pharmacological and pharmacological.

Andre felt that his grandfather, who had Alzheimer’s disease, was getting more repetitive in conversations and had started to lose his temper very easily. Suffering from the stress of caring for him, Andre and his family were considering sending his grandfather to a nursing home. Andre came to you, their family physician, to seek advice on what to do next. Andre admitted that he had lost his cool at times and raised his voice at his grandfather, but had felt very guilty afterwards.

WHAT ARE THE BEHAVIOURAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS OF DEMENTIA?

Dementia is a condition marked by the progressive and irreversible clinical syndrome of cognitive decline, which is eventually severe enough to interfere with daily living. Management of dementia is often complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach. This is the last article in our dementia series, after our previous two articles, ‘Approach to the forgetful patient’(1) and ‘Dementia management: a brief overview for primary care clinicians’(2) that discussed making the diagnosis and management of dementia. In this article, we discussed the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as agitation, insomnia, restlessness, hallucinations, anxiety and depressed mood. These can cause significant distress to families and caregivers, and may even lead to premature institutionalisation of the patient. Management consists of assessment of BPSD and supporting the needs of the family or caregiver.

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in dementia, with one population-based study showing that 80% of the cohort exhibited at least one symptom from the onset of cognitive symptoms.(3) The pattern of symptoms can vary over time and according to the stage of dementia. A Singapore study done in 1997 found that factors such as duration of care; presence of delusions, hallucinations, depression, insomnia, incontinence and agitation; and behavioural problems were significantly correlated with the impact on family caregivers of Chinese patients with dementia.(4)

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

First and foremost, the clinician needs to assess whether a recent-onset behavioural issue is due to BPSD or delirium (a reversible, acute confusional state due to underlying illnesses or disorders). Patients with dementia are more prone to developing delirium even after relatively minor insults, such as a sedating antihistamine, constipation or the common cold, due to reduced cognitive reserves. In delirium, the underlying causes should be managed or optimised, and patients can be reassessed subsequently. If it is indeed BPSD and not delirium, the condition can also be triggered or worsened by unmet needs. Looking for and addressing these factors is an integral part of the non-pharmacological management of BPSD, as they can contribute to the various BPSD mentioned in this article. Examples of unmet needs are: physical discomfort (e.g. pain, itch, constipation); unmet basic needs (e.g. hunger, thirst, sleep deprivation, boredom); restriction of independence (e.g. enforced diaper use, being stopped from going out); frustration at difficulties in communication or daily tasks; and unfamiliar surroundings or situations.

In general, there may be a low understanding of dementia, especially an appreciation of how it causes BPSD. It is not uncommon for family members to be convinced that the patients are being ‘naughty’ or behaving badly on purpose. Besides causing caregiver stress, this belief can contribute to strained relationships or even elder abuse. Hence, it is important to counsel family members that the behaviours are often part of dementia and affected by cognitive deficits due to dementia progression. The family physician should take an empathetic approach with the suffering caregivers, to reassure them that they will receive support and assistance. In all cases, BPSD management must be individualised for the patient and contextualised for the local community.

Non-pharmacological management

In the person-centred care approach advocated by Kitwood,(5) caregivers are encouraged to see the real person beyond the age or the disease, so that patients will be treated with more respect and dignity, as individuals. Having a meaningful relationship with the patients and knowing their likes and dislikes would make the work of caring less challenging. Caregivers are also encouraged to look at the positive aspects of the patients (i.e. what they can still do and enjoy doing), instead of emphasising the negative aspects.

The following are some common BPSD and the non-pharmacological strategies that the family physician can use to advise caregivers and family members of patients with dementia. Usually, there is no one single approach that works; hence, the caregiver needs to be innovative, try more than once and not give up easily. Caring may be augmented with technology such as smartphone and tablet applications if the individual patient enjoys them.

Insomnia

A reversed sleep-wake cycle is very common, can be associated with other behaviours and is often distressing to the family. Management is covered in the preceding article on dementia management.(2)

Agitation and aggression

In cases of agitation or aggression, identification of the trigger for the event is important. Besides the aforementioned unmet needs, agitation can also be due to paranoid delusions, hallucinations or disease progression. Agitation can also happen because patients resist help for activities of daily living (ADLs) due to poor insight (e.g. refusing to shower for days). In such cases, the caregiver should do the following: (a) appear calm and not argue with or restrain the patient; (b) approach the patient slowly, acknowledge that he/she is upset and reassure the patient that he/she will receive help, in short and simple sentences; (c) give the patient some time or space to calm down, while ensuring that the environment is safe by storing away dangerous items such as scissors or knives; and (d) set routines for ADLs, including regular toileting, and try to follow previous preferences for showering, such as timing and water temperature, if possible.

Repetitive behaviour

Patients may repeat a word, statement, question or activity over and over again. Despite appearing harmless, it can be very annoying and stressful for caregivers. Possible reasons for this repetitive behaviour are memory loss, anxiety, or the need to be occupied and have a purpose and structure to life. Using memory aids (e.g. written notes, signs, large clocks) may help repetitive questions, while distraction with activities or snacks, simple tasks such as folding clothes, and scheduled exercises to use up excess energy may help with repetitive asking (e.g. to go home, packing/unpacking of bags, or pacing up and down). If the patients have been confirmed to be safe, repeated phone calls from them need not be answered. On the other hand, if they are shouting for someone from the past, they can be allowed to talk about the person. In general, if the behaviour is not causing harm, it can be ignored. However, the family should ignore only the behaviour and not the person.

Paranoia and delusion

Paranoia can be the perception that a household member is stealing misplaced items or trying to harm the patients (e.g. poison), or that a spouse is being unfaithful. A change of environment or caregiver may worsen their insecurity and anxiety. Verification that the accusations are untrue is the first step. Confronting patients by arguing or scolding usually does not help and, in fact, may escalate the situation further. It is important to acknowledge any feelings or insecurities to calm them down. Distraction with another topic or activity may be needed.

The family needs explanation and support to not take suspicious accusations personally and to recognise that they are part of dementia. For accusations of theft, the family can show the patients that they are searching for the ‘missing’ items. Once found, they should be encouraged to keep the items in a place where they are easily available for inspection. For accusations of poisoning, patients should be allowed to participate in meal preparation.

Patients’ hearing and vision should be optimised; for example, treating impacted ear wax and referring to an ophthalmologist for cataracts. If relocation is needed, familiar items from the previous residence should be taken along, and having the same caregiver is preferable. These would help to maintain a familiar environment.

Wandering behaviour

Wandering may be due to boredom, discomfort, disorientation to time or place, continuation of a previous habit, memory loss causing patients to forget the destination, or searching for a familiar person, item or place. Patients should be engaged in another activity to be distracted from wandering. The wandering pattern, which may be time-specific or in response to certain situations, may help caregivers identify the triggering cause. As certain items such as keys and bags may remind them to wander, it may be advisable for these to be kept out of sight. If possible, patients should be accompanied when outdoors. They should also carry an identification card or bracelet with contact details in case they get lost.

Hallucinations

Patients may have auditory or visual hallucinations. For new-onset hallucinations, delirium may be the cause. Details of the hallucinations are important, such as what was seen or sensed, when, where and how long. It is important to try to identify the triggering factor such as any recent bereavement or change of medications. Hallucinations may be frightening for the patient.

As the experience may be very real to the patient, arguing that it is not real will not help. Acknowledgement that the patient is frightened and a calm explanation are usually helpful, although they may need to be repeated when the patient is calm and more rested. Distractions such as music, exercise, activities, conversations and looking at old photos may be useful. Good lighting in the room can help to eliminate shadows and may alleviate the hallucinations. For those who are afraid of the dark, a night lamp may help. Mild, harmless or non-distressing hallucinations may be ignored; however, hallucinations that cause agitation or potential harm will likely need pharmacological management.

In general, dementia day care centres can offer some respite for the family during the day. Initially, the patient may be hesitant to go to a new place or the family may be doubtful of the benefits. Frequently, once the patient starts participating actively in the various activities, BPSD will be less severe or frequent and nighttime sleep will improve.

Other resources for caregivers are dementia counselling, caregiver support groups, and dementia-friendly community programmes such as Family of Wisdom and Eldersit Respite Care by the Alzheimer’s Disease Association. Nursing homes also offer the option of short-term respite residential care.

Pharmacological management

Non-pharmacological measures for BPSD should be attempted first, as there are few side effects, if any. The other unmet needs listed earlier, including an uncomfortable environment, should be ruled out if possible. Failing that, or if the patient is at imminent risk of self-harm or hurting others, drugs may have to be considered.

In terms of pharmacological management, any physical symptoms contributing to BPSD, such as pain, itch or constipation, should first be treated with appropriate drugs and other measures. For pain, orphenadrine (often used in combination with paracetamol) should be avoided due to its anticholinergic effects, which may worsen confusion and cause constipation and urinary retention, while opioids should be used judiciously due to the potential for confusion and falls. For itch, first-generation antihistamines should be used cautiously due to their sedative and anticholinergic effects.

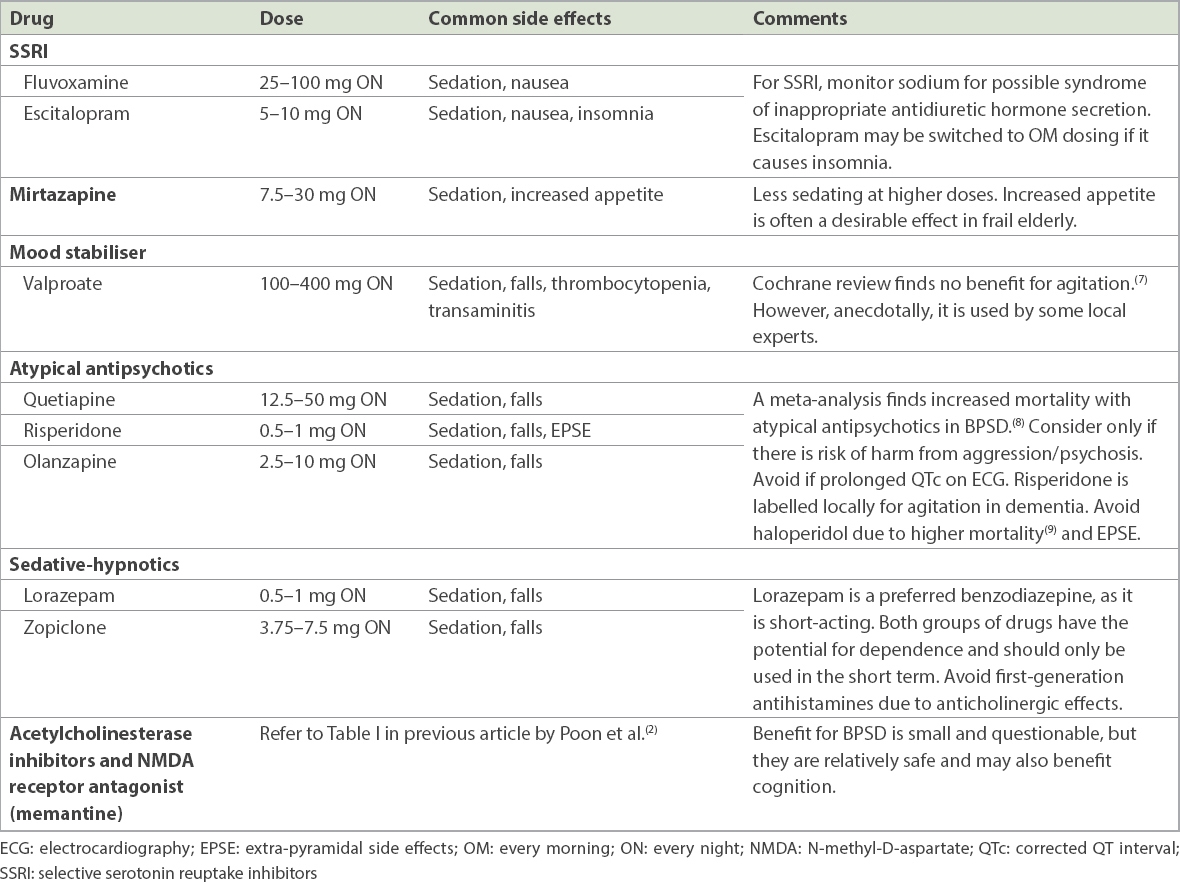

Among the more commonly used drugs, very few are actually labelled for use in BPSD, as the evidence is scanty and mixed. Hence, there should be appropriate caution before using ‘off-label’ drugs without a strong evidence base. Their use should be in the patient’s best interests, having weighed the risks and benefits, and consent should be obtained, as per the Singapore Medical Council Ethical Code and Ethical Guidelines 2016.(6) As the patient with BPSD usually cannot give consent, the family or caregiver should be carefully counselled. In view of the above, it is not possible to give an exhaustive list of drugs. Individual institution practices and preferences may also differ. Possible drugs used are shown in

Table I

Drugs used to manage behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

A possible approach is: for depression or anxiety symptoms, try antidepressant first; for mood lability, consider valproate; for predominant insomnia, consider sedatives; for severe psychosis and aggression or if unresponsive to other drugs, consider atypical antipsychotics. Cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine may be added for cognitive and possible behavioural benefits.

As the evidence is limited and the use of these drugs is mainly off-label, it is helpful to be guided and supported by the algorithm in the 2013 Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines on dementia.(10) Generally speaking, if BPSD is causing significant distress or risk, or initial trial drug treatment has failed, it is advisable to refer the patient to a specialist clinic, usually to a psychogeriatrician (i.e. a psychiatrist subspecialising in the elderly).

When starting a drug, follow the usual adage of ‘start low, go slow’. The clinician should identify a target symptom, such as a delusion that is causing distress, and review its response to treatment. As BPSD can evolve over time and there is potential for harm, drugs for BPSD should not be used in the long term, without regular monitoring and reassessment of the continued need for the drugs.

Elder abuse

Chronic demands on caregivers’ time and resources will increase with time. This may result in fatigue and stress for the caregivers and people living with them. When fatigue and stress are not identified and addressed, caregiver distress will result. These may lead to strained relationships, poor standard of care, neglect or even abuse of the person with dementia.(11) Elder abuse can be described as any action (commission) or lack of action (omission) by a person or caregiver that puts the health or well-being of an elderly person at risk. Elder abuse can come in various forms, including physical abuse, emotional and psychological abuse, and neglect. As healthcare providers, it is important to detect this early and report any suspected cases. You can refer the patient to the Ministry of Social and Family Development’s family violence brochure(12) or the TRANS SAFE Centre (a family violence specialist centre),(13) or call the ComCare hotline at 1800 222 0000.

USEFUL LINKS

Other useful resources for caregivers and patients include:Alzheimer’s Disease Association Singapore, Caregivers Corner: http://alz.org.sg/caregivers

Agency for Integrated Care: https://www.aic.sg

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia include presentations such as agitation, insomnia, restlessness, hallucinations, anxiety and depressed mood.

-

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in dementia, with up to 80% of patients in one study exhibiting at least one symptom from the onset, and the pattern of these symptoms can vary over time and according to the stage of dementia.

-

Clinicians must first assess if the new behavioural issue is due to BPSD or delirium from minor infections or common sedating medications that further affect patients’ cognition.

-

Even if delirium is excluded, BPSD can also be triggered or worsened by unmet needs that should be attended to, such as physical discomfort; unmet basic needs; restriction of independence; frustration at difficulties in communication or daily tasks; or unfamiliar surroundings or situations.

-

Besides causing caregiver stress, BPSD can contribute to strained relationships or even elder abuse.

-

Caregivers are encouraged to see the real person beyond the age or the disease, so that patients will be treated with more respect and dignity as individuals, within the context of a more meaningful relationship with the patient.

-

BPSD management must be individualised for the patient and contextualised for the local community.

You gave Andre advice on how to cope with the challenging behaviour of his grandfather and a list of useful websites to find out more about BPSD. His grandfather started attending a dementia day care centre in the neighbourhood thrice a week. On another review one month later, the family was coping better and had decided not to send the patient to a nursing home.

SMJ-59-518.pdf