Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Medical students rely on patients and their families as teachers during the learning journey. However, ill patients and their families may not welcome having students participating in their care, and anecdotal instances of abuse against clinical medical students are not uncommon. We aimed to determine the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by patients and their families and describe students’ self-reported responses to such incidents.

METHODS

An email link to an anonymised electronic survey form was sent to all clinical students (n = 184) at a Singapore medical school. The first part of the survey sought information on whether the student had previous experiences of mistreatment by patients and their families. If so, the frequency of mistreatment, circumstances when mistreatment happened and students’ reactions were collected. In the second part, the students were asked if they knew how to handle such mistreatment incidents.

RESULTS

There were a total of 91 respondents, 14.3% of whom had experienced mistreatment by patients and their families in our institution. One-third of the affected students felt fearful or humiliated. However, the majority chose to be passive by saying nothing or moving away. Less than half of the students knew how to handle such incidents or where to seek help.

CONCLUSION

Incidents of mistreatment in our school are not uncommon. Our study revealed a need for more clarity and guidance about how students can manage such situations. This is an important topic because such mistreatment is known to inflict emotional disturbance in students. We proposed a workflow to help students deal with mistreatment.

INTRODUCTION

Patients are an essential part of medical education, a fact that can never be overstated. As Sir William Osler stated in his famous quote, “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all”. Through interaction with real patients, medical students develop core skills such as critical reasoning, diagnosis and management of disease, communication, and professionalism. These skills are needed for the medical student to transition into becoming a physician.(1)

However, the participation of medical students in patient care may not be well received by the patients for a few reasons. As medical students, their main role in the medical team is to receive training. Hence, they are not viewed as an essential part of the medical team for patients’ clinical management. Secondly, patients’ willingness to discuss personal information and to be examined by medical students is affected by the patient’s sociocultural background and educational levels. While patients in Western countries generally feel comfortable with the presence of medical students, Asian patients have reduced receptivity to being interviewed or examined by medical students, as suggested by a local study, with differences between Chinese, Indians and Malays that are attributable to their own social and cultural norms.(2) The emotional stress from the pathological, social and economic burden of illness could further jeopardise patients’ attitudes towards the presence of medical students, which can range from indifferent to abusive.

Medical student mistreatment is defined as ‘behaviour that shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process, either intentional or unintentionally’.(3) It can take various forms, including physical or verbal abuse; humiliation; discrimination on the basis of race, religion, ethnicity or gender; sexual harassment; the use of grading in a punitive way; and even denial of access to opportunity. Mistreatment has been shown to lead to reduced self-esteem and confidence; burnout;(4) emotional and psychological disturbances;(5,6) and may be associated with increased substance abuse in medical trainees in an effort to ‘self-medicate’.(7) It also has negative effects on career choice, with students who reported mistreatment being less likely to plan a full-time career in medicine.(8)

Medical student mistreatment is a universal problem, with a pooled prevalence of 59.6% reported in a meta-analysis of 51 studies.(9) Patients or their families (21.9%) were cited as the second most common source of abuse after consultants (34.4%).(9) While mistreatment by the medical team is well reported, there is a paucity of studies focusing on medical student mistreatment by patients and their families, which remains poorly understood. One study in 2015 performed in a single institution in the United States reported a 15% prevalence in mistreatment experiences among paediatric trainees, and 67% of instances were by patients’ families.(10) Alarmingly, 50% of respondents did not know how to respond to these instances, while 25% believed no action would be taken if they alerted hospital leadership.(10) In the Asian context, a Japanese study in 2008 reported a high prevalence of medical student mistreatment of 68.5%, with patients being the third most common abusers, second to doctors and nurses.(11) Very few respondents (8.5%) reported their experience of mistreatment, and anger was the most frequent emotional response. Unfortunately, no subgroup analysis was available to specifically address students’ responses to mistreatment by patient and families. A study that specifically looks into student mistreatment by patients and families is needed in order to understand the issue better for development of preventative strategies. In our study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of the problem, the impact on the medical students, their responses towards it and what they understood as remedial measures.

METHODS

A cross-sectional survey was performed using an online questionnaire to estimate the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by patients and families. Study subjects included all medical students doing clinical training years from one medical school in Singapore. The duration of medical training is four years, with clinical training taking place from the second to the fourth year. From May 2016 to October 2016, all medical students from Year 2 to Year 4 were contacted by email with an anonymous online survey link. A copy of the participant information sheet was provided to all students via the email. Implicit consent was derived once the student clicked on the link to the survey, indicating that the student agreed to participate in the study.

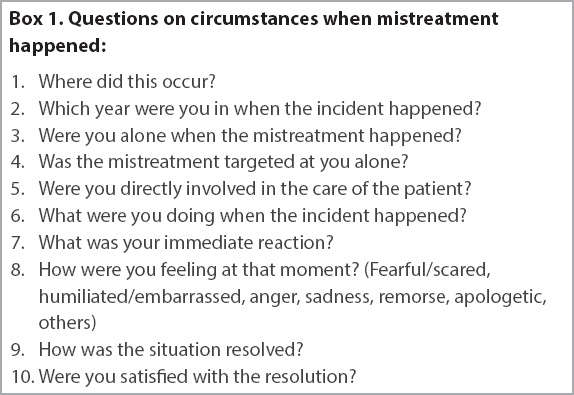

Student characteristics, including year of study and duration of clinical clerkship, were collected at the beginning of the questionnaire but not other demographic information, to ensure confidentiality. The questionnaire began with a screening question that asked if the student had experienced any previous mistreatment by patients and families. Bearing in mind that the definition of mistreatment can be subjective and up to individual interpretation, we provided examples of mistreatment behaviours in order to help the students identify or classify a mistreatment event. Such behaviours included verbal abuse such as shouting, yelling, demeaning, insulting or threatening comments, actual physical abuse, unwanted physical contact, and perceived physical abuse such as cornering the student. If the student answered ‘yes’ to previous mistreatment by patients or the families, details such as frequency of mistreatment, circumstances when the mistreatment happened, students’ reactions and how the situation resolved were collected (

Box 1

Questions on circumstances when mistreatment happened

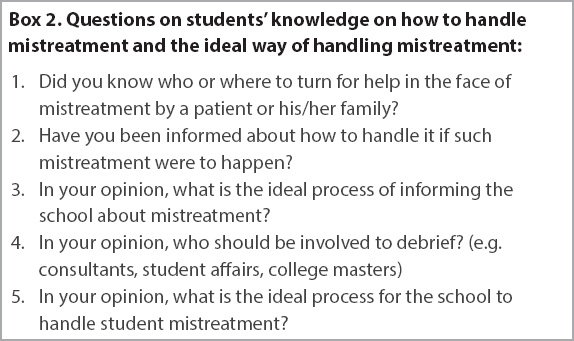

The second part of the survey explored whether the student knew how to handle mistreatment and where to look for help. They were also given an opportunity to voice their suggestions regarding the ideal way of handling mistreatment (

Box 2

Questions on students’ knowledge on how to handle mistreatment and the ideal way of handling mistreatment

The free-text responses were analysed using frequency count. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of proportions were calculated using a web application (

RESULTS

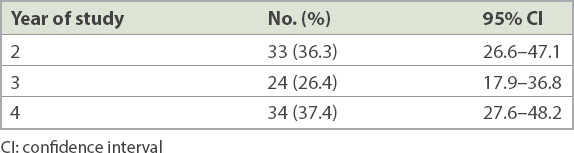

A total of 91 (49.5%, 95% CI 42.1–56.7) out of 184 students responded to the survey. Out of these 91 respondents, all questions were completed by 77 (84.6%, 95% CI 75.2–91.0) students. Analysis of the data took into consideration the survey questions that might have been incompletely answered. Respondents were fairly equally represented over the three clinical years (

Table I

Demographic data of students surveyed (n = 91).

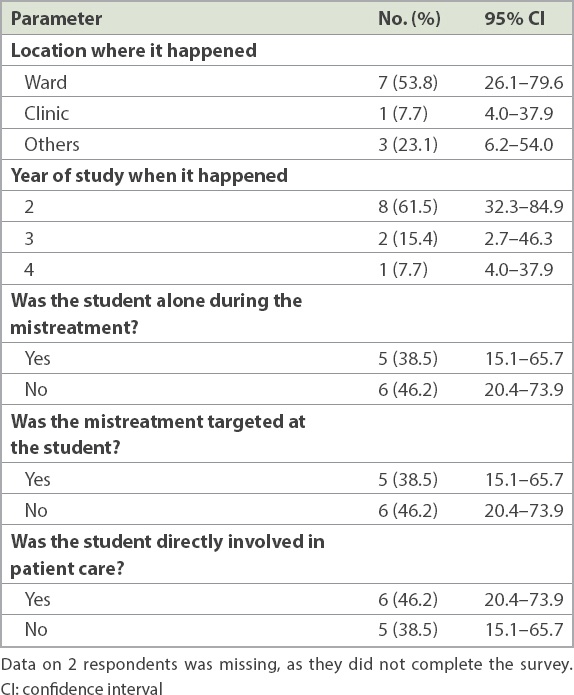

Mistreatment by patients or their families was reported by 13 (14.3%, 95% CI 8.1–23.6) out of 91 students. Multiple episodes of mistreatment happened to four students, making up 30.7% (95% CI 10.4–61.1) of the 13 students. As shown in

Table II

Circumstances when mistreatment took place (n = 13).

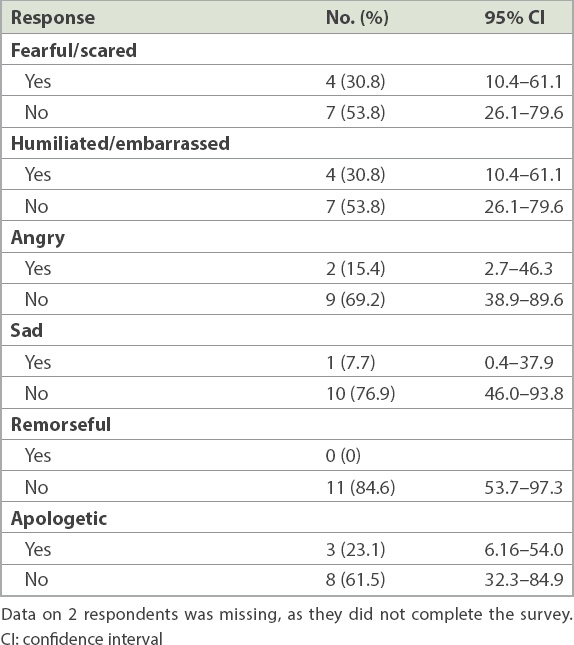

One-third of the students felt fearful or humiliated after the mistreatment (

Table III

Students’ emotional response after mistreatment (n = 13).

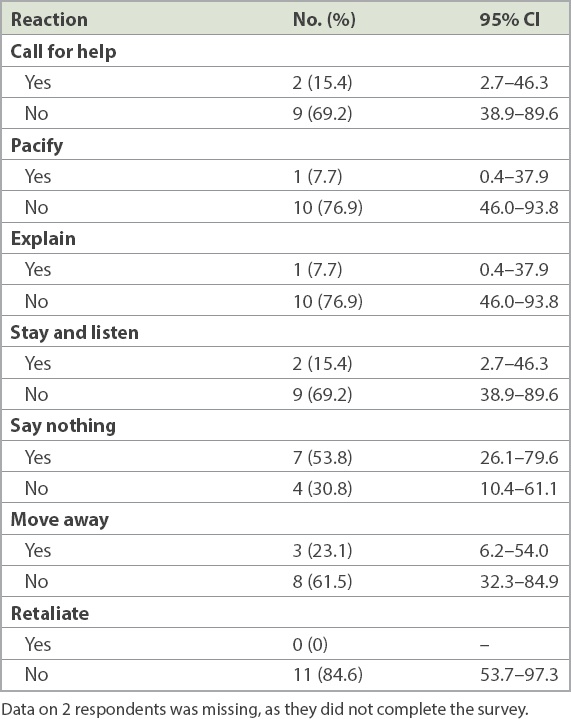

Table IV

Students’ immediate reactions following mistreatment (n = 13).

Of note, among students who reported having received several episodes of mistreatment, three students described ‘feeling numb’. The most frequent response was to ‘say nothing’. In 6 (54.5%, 95% CI 24.6–81.9) of the cases, the situation was resolved after another member of the team intervened. More than half of the students (61.5%, 95% CI 32.3–84.9) were satisfied with how the incidents were resolved. Among the 91 students who responded to the question on looking for help, less than half of the students (42.9%, 95% CI 32.7–53.7) knew who to turn to or where to look. Only 33% (95% CI 23.7–43.7) said that they had previously been informed about how to handle mistreatment.

For the reporting process, anonymity was brought up as a priority by close to one-fifth of the students. About one-fifth of the students felt that the mistreatment incidents should be reported to stakeholders from the medical school, including the Department of Student Affairs, deans, faculty members and mentors. Others suggested that such incidents should be reported to faculty members on the ground, such as consultants in charge of the patient and the student’s clinical mentor or clerkship directors. Students suggested that those incidents should be investigated thoroughly, but on the premise that anonymity is preserved and support provided to the student involved. A debrief by either faculty members from the school or clinical staff was viewed as desirable following investigations.

Students did not identify themselves to receive psychological support even when they were encouraged to do so. Instead, they left free-text answers in the survey such as ‘depends’ or ‘I don’t take things personally so no problem’.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of medical student mistreatment by patients and their families in our study was comparable to that reported in the West(3,10,14) but slightly lower than that in Japan and Arab countries.(11,15,16) These differences could have been a result of culture, education system and patient demographics. While Singapore mainly comprises Asian ethnic populations, it contains a blend of Western and Asian cultures, hence local patients may have a different outlook from traditional Asians.

Our study suggested that medical students at more junior years of training were possibly at higher risk of mistreatment by patients. As junior clinical students are less familiar with the clinical environment and patient encounters, they may have higher levels of anxiety and emotional stress.(17) Their medical knowledge and skills would also be less comprehensive. Patients and relatives may detect this and see them as being less experienced and confident, adding to their vulnerability.

The students’ reactions after being mistreated were worrisome, as the majority of the students in this study did not speak up or call for help after a perceived mistreatment incident occurred. This failure to react may be due to several reasons. The student may not have recognised the severity of such incidents; it was reported that a significant number of students deemed mistreatment incidents as not serious enough to warrant action.(18) Second, students may have chosen to remain quiet for fear of aggravating the situation further or were afraid of reprisal.(3) Third, the students may not have known how to manage such encounters and where to look for help. The learning value of reflecting from negative experiences has been advocated(19) and may need to be emphasised to our students. Our study also revealed possible inadequacy in student support, as only one-third of the respondents reported being previously informed of how to handle such incidents.

Mistreatment by patients and families has negative consequences and is potentially traumatising to young, learning minds. A number of students reported feeling scared, humiliated, sad or angry. Repeated exposure to mistreatment by patients may be associated with psychological harm, as students reported feeling ‘numb’ afterwards. Such a description, while subjective, might have reflected ennui, a degree of helplessness, frustration and desperation. In view of the negative effects, recommendations on strategies to protect our students from the negative consequences of mistreatment are needed. These can be classified as primary strategies that aim to prevent a mistreatment event from happening or secondary strategies that aim to reduce the negative impact as much as possible after mistreatment. Primary measures can be implemented through education to better prepare the students, with support from the hospital and clerkship team, as well as raising public awareness about the issue.

Students can be trained on non-technical skills such as situation awareness, communications and mastering difficult interactions. They should also be empowered to take action should mistreatment happen, such as withdrawing from a traumatising scenario, reporting to seniors or taking further steps to escalate the situation to persons in authority. All have a duty to ensure a safe environment for medical students rotated to them. A proactive stance would include introducing students as members of the team, thereby informing patients and their families that the medical student is a provider of healthcare too. Clerkship directors should also discuss contingency plans for possible mistreatment with their ward staff, so that everyone is aware of their role in damage limitation.

Among the public, awareness should be raised that mistreating hospital staff including medical students is prohibited and liable to be prosecuted in certain situations. This is supported by the Protection from Harassment (Public Service Worker) Order, enacted locally since 15 November 2014.(20) Roadshows, banners and posters can be set up in wards and clinics as reminders. Patients who are known to mistreat medical students should be identified and any clinical encounter should be avoided, or supervised if it is inevitable.

After mistreatment has happened, secondary measures are important to prevent the situation from deteriorating further. The safety of the student is a priority and getting help to the scene may be the most important action if there is any danger of violence, and help must be readily available whenever the situation arises.

No mistreatment incident is too trivial to report, and every case may have learning value. In order to facilitate the reporting and handling of mistreatment incidents, a formal mechanism should be developed and publicised so that both students and ward staff are familiar with the necessary actions to take. We can emulate a system similar to that of the David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, USA, which created a committee investigating the prevalence of student mistreatment, policies to prevent mistreatment and a mechanism for reporting, educating staff, and providing resources for counselling.(21)

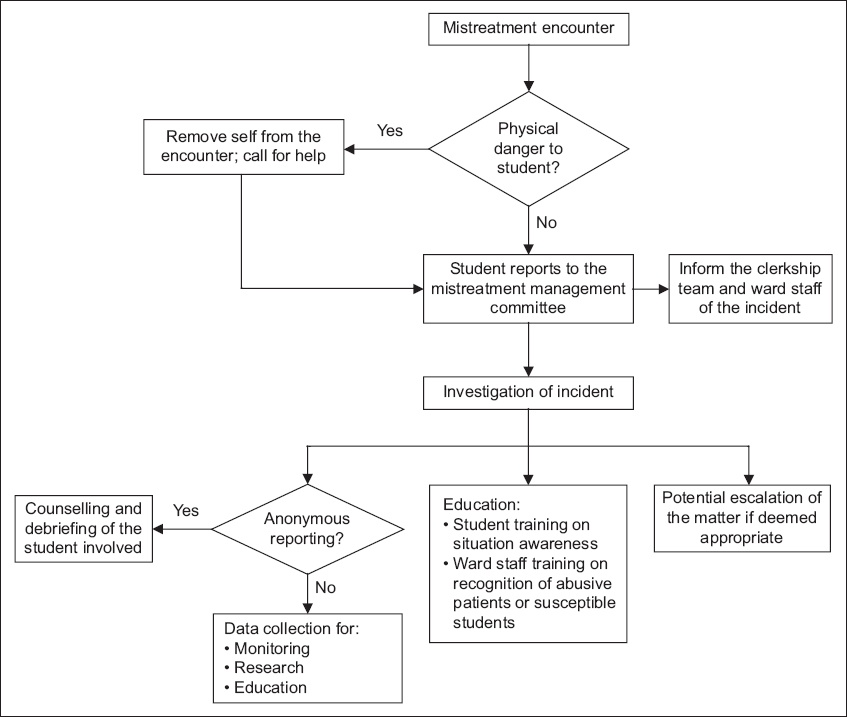

The suggestions that we gathered from our students will be useful for formalising such a mechanism. A committee can be set up to specifically address the issue of medical student mistreatment, ideally consisting of stakeholders from both the medical schools and teaching hospitals. A student making a report in the clinical environment would not need to go back to the school to formally make a similar report. The committee should review and investigate reports of incidents, preferably in an anonymous manner, and decide on the appropriate actions to be taken. The affected students may be counselled by selected faculty members whom the students find comfortable speaking to. Actions also include notifying the clinical department involved and hospital leadership. In serious cases, escalation may be warranted for potential prosecution. This sends a message that such reports of incidents, if meritorious, will receive full attention and support. Lastly, the committee may use the collected data to perform research on behaviour patterns in both perpetrators and victims, which may further contribute to the formulation of strategies in managing medical student mistreatment. A workflow (

Fig. 1

Flowchart shows the proposed workflow for the management of medical student mistreatment by patients and their families.

To our knowledge, this is the only local study that has looked into the issue of medical student mistreatment by patients and their families. The results may not be generalised to all three medical schools nationwide due to several limitations of the study. First, it was conducted in a single institution with a modest sample size. This was further limited by the low response rate of the survey and possible self-selection bias in those who chose to participate. Furthermore, some survey forms were incomplete. Second, our study was retrospective and therefore subject to recall bias. Third, although we defined medical student mistreatment and listed examples of mistreatment behaviours, mistreatment is still a subjective experience that is up to individual interpretation. Hence, judgement and interpretation of what constitutes mistreatment may vary among respondents. However, by virtue of the cohort’s maturity, our assumption that respondents would give proportionate and fair replies to the survey was not unreasonable.

In view of the above limitations, future studies are needed to better understand the problem on a national scale. Suggestions for improved generalisability include studies with a large sample size and a fair representation of students from all three medical schools. The survey questions could also be improved to incorporate information that would allow subgroup analysis such as demographics of the students, including age and gender, as well as the types of clerkship. Triangulation could be done to get multisource and multimethod data, such as through focus group discussions with patients and families, and patient/family surveys on attitudes towards medical students participating in their care. However, sensitivity and privacy issues preclude easy access of data from schools regarding students who need support. Students should be empowered to provide truthful responses for the survey while preserving the confidentiality of the data.

Disappointingly, the World Federation for Medical Education’s 2015 Global Standards for Quality Improvement in Basic Medical Education (Section 4.3) makes a very brief mention of student support, while the United Kingdom Quality Code for Higher Education exhorts treating students with fairness, dignity and respect without much detail.(22,23) We contend that medical student mistreatment by patients and families is an issue that needs consideration and publicity. Medical schools and clinical areas have a duty to ensure the safety and dignity of students at places of training. Despite the stated limitations of the study, the findings may alert the school about the problem as a first step in quality enhancement of its curriculum.

Most doctors would have encountered some form of mistreatment by patients and families during their student days. Many take this in their stride, accepting it as part of medical training. Some may feel that medical students, who are young adults, should have the maturity to look after themselves. In situations where overt violence or threats happen, the management decision is clear – personal safety comes first and hospital security would need to be involved. Mistreatment that is subtle, hurtful and undermining is less easy to manage. However, that is in itself a lesson that medical practice is not always gratifying and may reflect the less pleasant aspect of the human condition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Dr Mara Catherine McAdams for her support in the implementation of the study in the medical school.