Janet visited your clinic for a cough of three days’ duration. She asked for some sleeping pills, as she had not been sleeping well after she started working from home last month due to movement restriction measures to limit the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). She said she was worried about her job stability and her family or herself catching COVID-19. She also had to cope with increased household chores in the past month.

WHAT IS THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC?

COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) is predominantly a respiratory illness caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was previously known as the 2019 novel coronavirus. The illness was first noticed in late 2019 and soon spread around the world, causing widespread mortality with case fatality rates of 0.06% in Singapore, 1.37% in Australia, 14.5% in Italy and 19.1% in France in late June 2020.(1) In mid June, five months after the alarm about SARS-CoV-2 was first raised, there were more than 8.65 million confirmed cases and 460,000 deaths worldwide, with numbers still rapidly rising in some countries.(1) As of 21 June 2020, Singapore has confirmed more than 41,800 cases of COVID-19 and had 26 deaths over the same period.(2)

The route of transmission and infectivity period of COVID-19 are still being understood.(3) The main mode of transmission is via respiratory droplets from coughs, sneezes and speech onto mucous membranes. Touching a contaminated surface followed by the mucous membranes may contribute to transmission. Airborne transmission is also a risk in aerosol-generating procedures such as airway intubation and nebulisation. The incubation period is up to two weeks with a median of five days. The infectiousness of the virus is high 2.3 days prior to the onset of symptoms and declines after 7–10 days of symptoms.(3,4) In a subset of asymptomatic patients, infectivity is likely to be lower based on our understanding of the route of transmission.

The pandemic has resulted in far-reaching changes and impact on society. Many countries have implemented and even mandated the use of face masks, physical distancing and movement restriction measures, including closure of businesses, schools and care centres, working from home, and even the lockdown of entire cities and provinces. Many in the general population are worried about their income and even their daily meals. The world is also preparing for a prolonged economic depression.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

There is much anxiety and fear due to the high infectivity, severe morbidity and mortality, uncertainty, and changing knowledge and information brought about by this new virus. Measures to mitigate damage such as protective equipment and movement restriction measures, including social isolation and business closures, affect everyone and have caused considerable stress. Other man-made sources of stress include stigmatisation, the spread of false information and scams.

Healthcare providers and systems have also had to rapidly adapt to the situation by adopting new safety protocols and acquiring protective equipment, new knowledge and new information about the pandemic and response measures. We also had to handle new or greater work responsibilities, while some have been compelled to stop non-essential medical services. Some healthcare providers may also face stigmatisation from the public.

This article focuses on mental health and psychological support, which are often neglected or lacking during and after healthcare emergencies.(5) Attention to psychosocial support during crises is important, as better mental health is associated with positive outcomes such as improved physical health, productivity, relationships and social network.(6)

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

A holistic clinical approach helps us to recognise the stress that everyone faces.

Screening and recognising the need for psychosocial support

In view of the widespread impact that healthcare emergencies exert on the population, it is prudent to – before, during and even after the crisis – screen and look out for patients who may need psychosocial support.

People at risk include those who have suffered from COVID-19 or whose family members were infected, and those whose income or basic needs have been affected. Patients with a history of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and substance abuse are also predisposed to coping difficulties. Furthermore, there is a greater risk of domestic abuse during emergencies, especially with movement restriction measures during COVID-19.(7-9) Examples of screening tools include the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (i.e. PHQ-2) for depression and the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale.

Assessing the level of need and management required

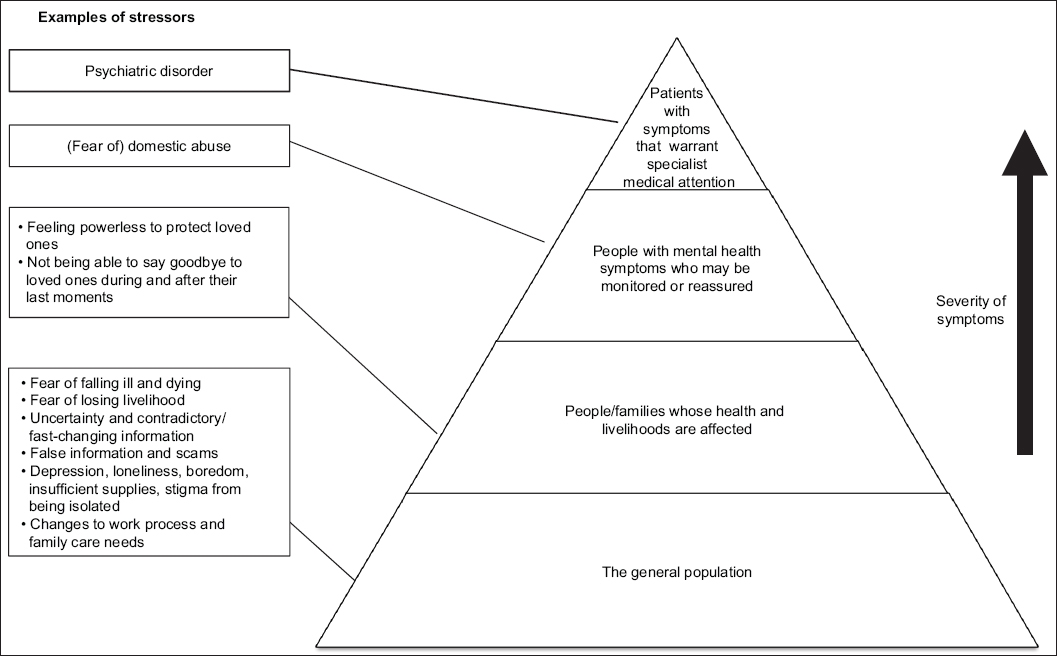

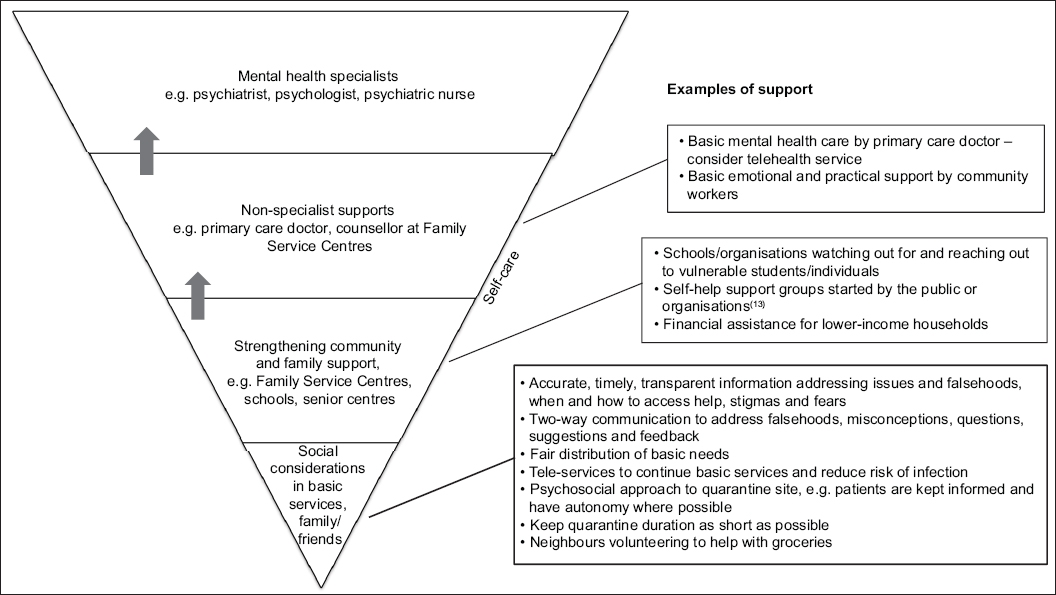

Psychological first aid(10) is a non-intrusive, practical intervention that a trained individual from any walk of life can use to help stabilise the affected person. All frontline workers should be trained in psychological first aid. First, determine the safety of both the psychological first aider and the affected person. Second, ensure that emergency or urgent needs are attended to before commencing psychological first aid. Examples include life-threatening conditions, basic need for food and shelter, and psychological red flags that require urgent specialist attention. After making sure that the first two conditions are met, we can attempt to help the people who may need support: ask them about their needs and concerns, and listen to them. Do not pressurise them to speak, instead giving them the time and space to share. Normalising stress and allowing silence may be useful in some situations. Having heard them, help them to feel calm and to problem solve, link them to useful information, resources and services, and help them to connect with loved ones and social support. Identify the level of mental health need (

Fig. 1

Pyramid representation shows the spectrum of the population that requires mental health and psychosocial support as well as some examples of mental health stressors. The majority of the population have mild psychological symptoms and form the base of the pyramid. The pyramid tapers towards the top, with the number of people decreasing as the severity of symptoms increases. These levels and demarcations are not rigid and are for illustrative purposes.

Fig. 2

Inverse pyramid representation shows the amount of mental health resources typically used to attend to the needs of the population and some examples of psychosocial intervention. Self-care is important and applicable to everyone. Arrows: refer if red flags noted.

Having a keen knowledge of existing formal and informal resources can be very useful, including patients’ family and friends; fellow colleagues or professionals; community leaders; schools; centres for the elderly, the youth and the vulnerable (e.g. those with disabilities); social workers; and the healthcare system. Some mental health and psychosocial support helplines including online counselling options in Singapore are listed in

Box 1

Mental health and psychosocial support helplines in Singapore (accessed 29 June 2020):

Self-care and healthy coping strategies are important and applicable to all individuals. These include healthy diet, sleep, physical and relaxation exercises, maintenance of social contact, avoidance of unhealthy habits (e.g. spending too much time looking for information on the outbreak), and avoidance of unhealthy substances such as tobacco, alcohol and other drugs to cope with one’s emotions. Some people may be able to draw on life skills and experience gained from previous adversity to help them cope with the present situation. For those who are unaccustomed to accepting or seeking help and support, we can advise that it is normal for people to require support from one another during a crisis and that taking good care of oneself is a form of responsibility towards others.

The following five principles have been found to be helpful in psychosocial interventions.(11,12) In applying these principles, we should also be mindful of the culture of the affected person. We should foster a sense of: (a) safety – educating people on what they are dealing with (e.g. a viral infection) and how to protect themselves; (b) self and community empowerment – help people learn how to inform and equip themselves with reliable information and how to seek help (Box 1); (c) connectedness – keeping in touch with family and friends/support network (through calls and technology during a movement restriction period), promoting social interaction and activities through outreach activities by care and community centres; (d) calm – reassurance, addressing falsehoods and providing strategies and advice on relaxation and calming techniques using various media including print, television, radio and online videos and apps; and (e) hope – public communication to focus on what is being done, resources available to help affected people, hopeful messages and stories of people who have overcome their difficulties.

Before discharging patients from a consultation, educate them on red flags that should prompt them to seek help or medical attention and how they can do so.

Monitoring and reviewing patients

We should review and monitor patients whom we are managing to ensure that our treatment and recommendations are working and to identify red flags that indicate a need to escalate care or seek further help from community partners. Besides face-to-face consults, teleconsultation can be considered for selected patients. It is also good practice to check in with patients whom we have referred for further management in the community or for further psychiatric management.

The periods of movement restriction and the aftermath of the emergency are good times for individuals to examine and reflect on what is important to them, lessons learnt, what was helpful or unhelpful, and how they can and will do better. Likewise, it is helpful for us and for our society to continually review and refine our objectives, processes and systems.

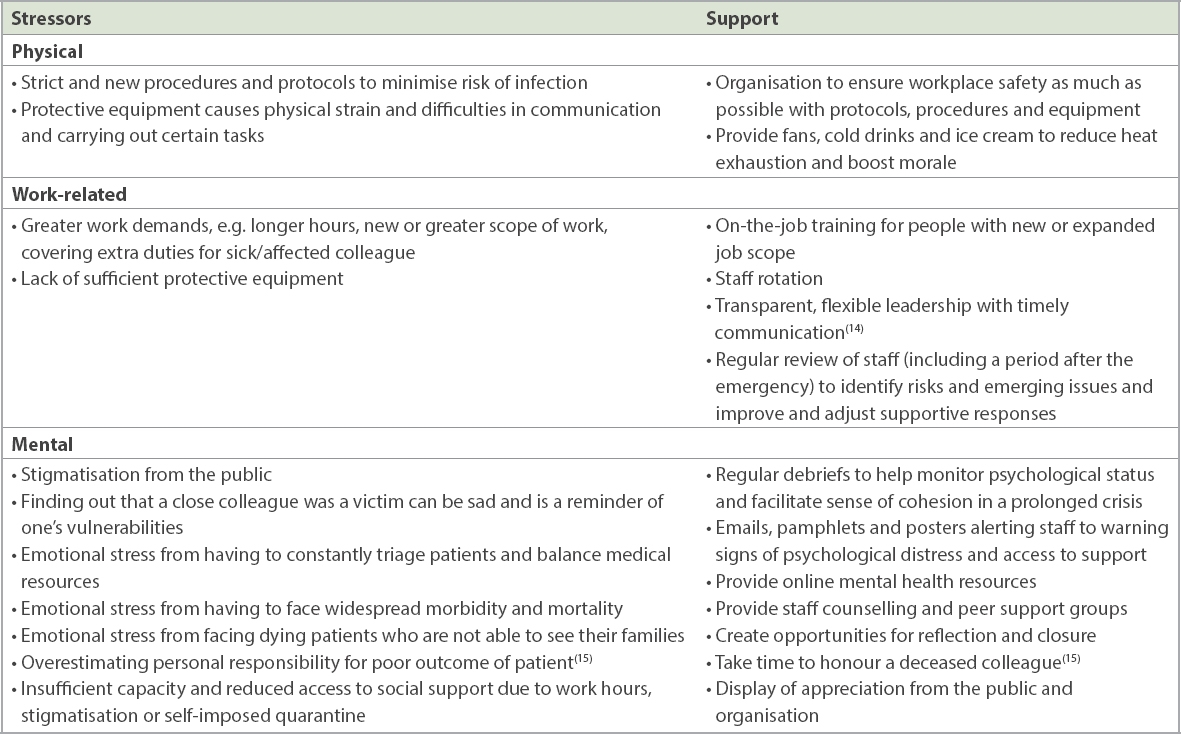

Caring for healthcare and response workers

Healthcare and response workers have similar mental health and psychosocial needs during healthcare emergencies. Examples of stressors and interventions that are more pertinent to healthcare and response workers are found in

Table I

Examples of stressors and support for healthcare and response workers.

The role of the workplace or agency can also make a significant difference to the well-being of workers. The healthcare or response worker may offer feedback or ideas to improve staff or organisational performance and coping. The workplace should institute procedures and equipment to ensure workplace safety and look out for staff who may need additional support, including psychosocial support and on-the-job training for those who may not be familiar with work in the setting of healthcare emergencies or those who have had a change of job scope. Transparent and flexible leadership with timely updates and communication will also help to reassure and empower staff.(14) Other measures that organisations can take to support their staff include staff rotation to reduce burnout and assist with coping; providing online mental health resources in addition to traditional counselling and peer support to increase access to support; showing appreciation for good work; and boosting staff morale during these difficult times.

In Singapore, the Public Health Preparedness Clinics (PHPC) scheme,(16) previously called the Pandemic Preparedness Clinic scheme, is a strategy by the authorities to promote primary care clinic response to public health emergencies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PHPCs are supplied with protective equipment and patients can receive medical attention and treatment for respiratory illness at a subsidised rate. Besides equipment and medication supply, the PHPC scheme also provides training and refreshers to help the healthcare provider keep up to date with the skills and knowledge required for an emergency response. The results of the SARS-CoV-2 tests performed by PHPCs and the public institutes are accessible to healthcare providers who have access to the National Electronic Health Record system. Singapore citizens and permanent residents are also able to access their SARS-CoV-2 test result on applications such as HealthHub SG and Health Buddy. These measures may help to allay some of the worries of healthcare providers, patients and the public.

CONCLUSION

Healthcare emergencies threaten the mental health of many people. We should screen and look out for at-risk patients who may require psychosocial support, which ranges from informal support from family and friends to help from community services, their primary care doctor or specialist psychiatrist attention. The key is to identify the level of support needed and to manage or refer patients as indicated. Patients should be monitored and reviewed to ensure that there is sufficient care and support. During these busy and difficult times, it is also important to take care of our own mental health.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Safeguard the mental health and psychosocial support of patients during healthcare emergencies to promote resilience and better health, productivity and relationships.

-

Screen and look out for patients who may require psychosocial support before, during and even after healthcare emergencies. At-risk patients include those who are affected by the emergency, those who have a history of psychological disorders, and marginalised individuals with poor socioeconomic backgrounds or disabilities.

-

Identify the level of psychosocial support needed for each patient and manage or refer them to the community or specialist psychiatric unit as indicated. Educate the patient on when (i.e. red flags) and how to seek further help. Review patients and adjust the management plan accordingly.

-

Familiarise yourself with support services and systems available in the community and how to refer patients to these services. These include community leaders, schools, centres for the elderly, the youth and the vulnerable (e.g. those with disabilities), social workers, counsellors and healthcare workers.

-

Practise and encourage self-care and healthy coping strategies for all. These include healthy diet, sleep, physical and relaxation exercises, maintenance of social contact, and avoidance of unhealthy habits and substances.

-

Empower patients and help them to feel safe, calm, hopeful and connected to a support system.

You shared with Janet your assessment that her current anxiety and stress levels can be managed with some support from her family. You advised her to manage her insomnia without the use of drugs and pointed her to the HealthHub website for some stress management and relaxation strategies. You suggested that she can share some of her responsibilities with her husband and come up with a schedule for her son. Besides giving her contacts for phone and online counselling helplines, you also directed her to the mycareersfuture.sg and workfare.gov.sg websites to find out more about job opportunities and skills upgrading if she was still worried about her job security. You asked her to visit your clinic again if her respiratory symptoms and anxiety do not improve soon. She agreed with your plan and thanked you for your advice.

SMJ-61-362.pdf