Abstract

Asthma is a reversible chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that can be effectively controlled without causing any lifestyle limitation or burden on the quality of life of the majority of asthma patients. However, persistently uncontrolled asthma can be frustrating for both the patient and the managing physician. Patients who fail to respond to high-intensity asthma treatment fall into the category of ‘problematic’ asthma, which is further subdivided into ‘difficult’ asthma and ‘severe refractory’ asthma. Establishing the correct diagnosis of asthma and addressing comorbidities, compliance, inhaler technique and environmental triggers are essential when dealing with ‘problematic’ asthma patients. A systemic approach is also crucial in managing such patients. This is pertinent for general practitioners, as the majority of asthma patients are diagnosed and managed at the primary care level.

Mr Tan, a 45-year-old man, was diagnosed with asthma a year ago by his general practitioner. He suffered from nocturnal cough, associated with chest tightness, every other night. His inhaler therapy has been up-titrated over the past year to Seretide 50/500 one puff twice daily and salbutamol two puffs pro re nata. He had two episodes of acute asthma exacerbations last year, requiring short courses of oral systemic corticosteroids. He was worried about his persistent symptoms despite the increase in his inhalation medications, and came to you for a second opinion on the management of his asthma.

WHAT IS ‘PROBLEMATIC’ ASTHMA?

In 2011, the Innovative Medicine Initiative released an international consensus statement regarding patients with chronic severe asthma symptoms. There were three classifying terms proposed: (a) ‘problematic’ asthma; (b) ‘difficult’ asthma; and (c) ‘severe refractory’ asthma.(1-3)

The ‘problematic’ asthma group includes all patients with asthma and asthma-like symptoms that remain uncontrolled despite the prescription of high-intensity asthma treatment, which is defined as treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) combined with a second controlling medication (e.g. long-acting beta agonist [LABA], leukotriene receptor antagonist and theophylline). The ‘problematic’ asthma group includes patients with ‘difficult’ asthma and ‘severe refractory’ asthma.

The ‘difficult’ asthma group consists of patients with asthma that remains uncontrolled despite the prescription of high-intensity asthma treatment, due to the following factors:

Incorrect diagnosis of asthma. Existence of comorbidities known to aggravate asthma, e.g. allergic rhinitis. Poor compliance to medications. Persistent exposure to triggers of asthma from the environment. The diagnosis of ‘severe refractory’ asthma is made when the following conditions are met:

Elimination of the aforementioned factors contributing to ‘difficult’ asthma, Current administration of high-intensity asthma treatment, and Persistence of poorly controlled asthma, defined as

Poor control of asthma symptoms, Frequent (> 2) severe asthma exacerbations per year, or Continuous or near-continuous use of systemic corticosteroids to maintain asthma control.

HOW COMMON IS ‘PROBLEMATIC’ ASTHMA?

‘Problematic’ asthma patients represent an estimated 5%–10% of the asthma population.(4) Although it comprises the minority of asthma cases, ‘problematic’ asthma remains a frustrating disease for both patients and clinicians. These patients also account for a disproportionately higher share of healthcare demand, with poor outcomes.(5,6)

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

‘Problematic’ asthma patients experience severely impaired quality of life and are at higher risk of asthma exacerbation, hospitalisation and death. Distinguishing ‘difficult’ asthma from ‘severe refractory’ asthma is imperative because ‘difficult’ asthma patients can achieve good asthma control when the four factors mentioned earlier have been considered and addressed.(7,8) Several of those factors can be identified with careful clinical assessment and managed at the primary care level. On the other hand, ‘severe refractory’ asthma patients would benefit from respiratory specialist review so that other types of therapy can be considered.(4)

WHAT SHOULD I DO WITH A ‘PROBLEMATIC’ ASTHMA PATIENT?

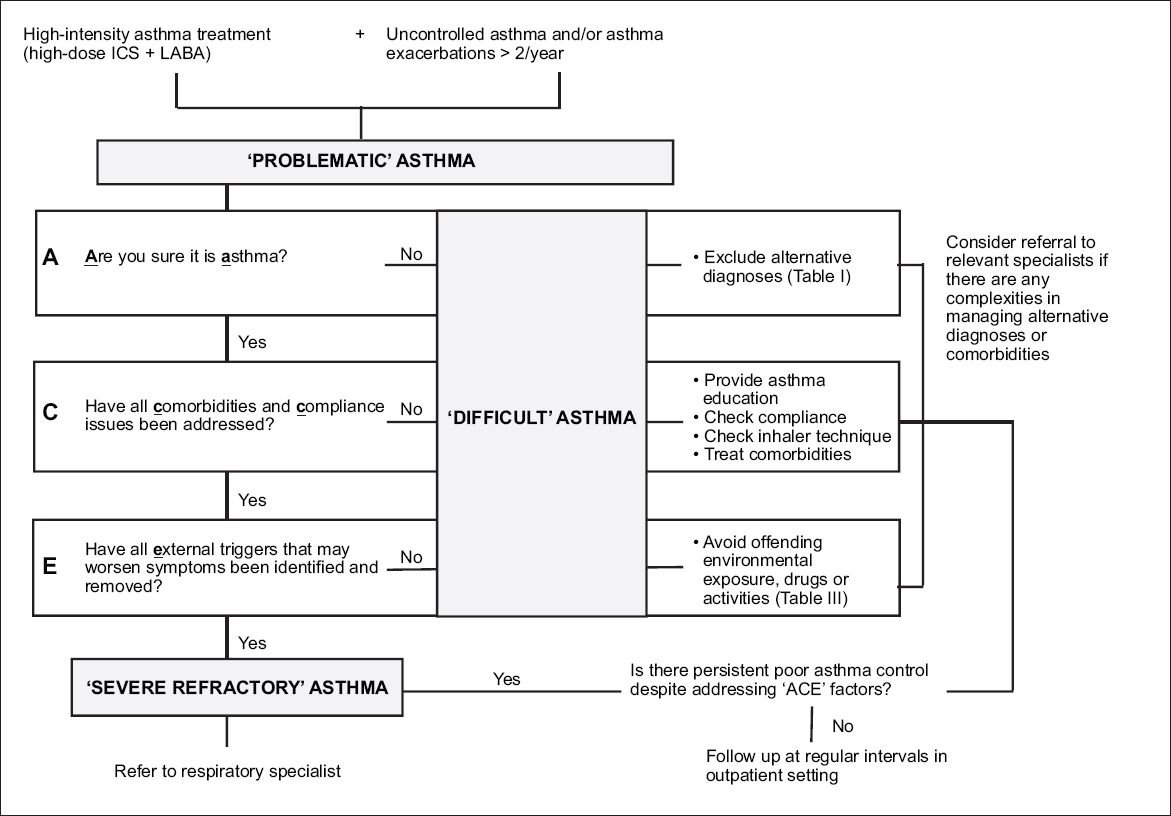

A systemic evaluation is essential in the management of patients with ‘problematic’ asthma. This should include the confirmation of diagnosis and the evaluation of risk factors, comorbidities, compliance and external factors that prohibit asthma control. There is currently no validated algorithm available to define the most useful approach in managing ‘problematic’ asthma.(9) We propose an approach based on the mnemonic ‘ACE’ (

Fig. 1

Chart shows a suggested approach in managing ‘problematic’ asthma patients. ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; LABA: long-acting beta agonist.

Are you sure it is asthma?

A study by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence showed that almost a third of patients have been misdiagnosed with asthma. There is currently no gold standard test available to diagnose asthma. Diagnosis is often made in a primary care setting and based on conscientious history-taking with emphasis on asthma symptoms that are variable, such as episodic wheezing, dyspnoea, chest tightness and cough with nocturnal, seasonal or exertional characteristics.(10) It is also important to exclude symptoms that are not typical of asthma, such as cough with haemoptysis or progressive shortness of breath. In the primary care setting, physicians may use serial peak flow measurements to support the diagnosis of asthma by demonstrating variable airflow limitation. Repeated failure to demonstrate variable airflow obstruction over time and the need to escalate to high-dose therapy for persistent non-resolving symptoms should raise suspicion of alternate diagnoses.(11)

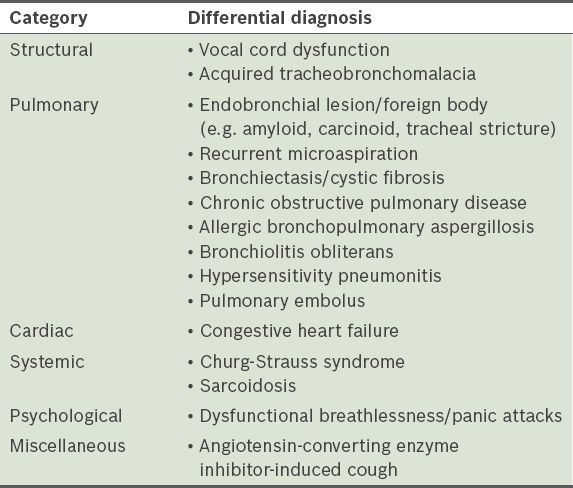

Several conditions may mimic asthma and be mistaken for severe asthma, as these conditions do not respond to high-intensity asthma treatment.(1-3) Common conditions that may be misdiagnosed as asthma are listed in

Table I

Common mimics of asthma.

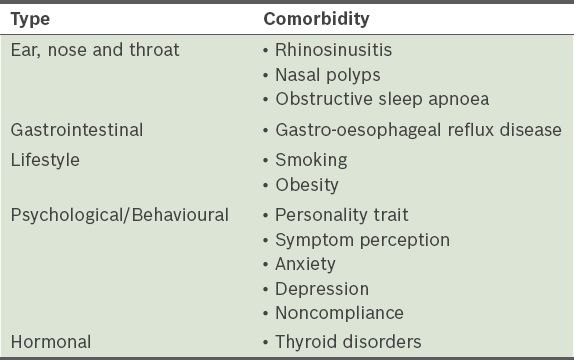

Comorbidities and compliance

Mild-to-moderate asthma can be misdiagnosed as severe asthma due to the presence of untreated comorbidities and/or noncompliance.(12) These comorbidities are listed in

Table II

Asthma-related comorbidities.

There are reports showing that noncompliance can be as high as 32%–56%.(7,8,13) Adherence to ICS is inversely correlated to the number of emergency department visits and courses of oral steroid therapy. Reasons for not taking prescribed medication include complexity of treatment, perception of inefficacy, side effects and cost. Incorrect inhalation technique is also frequently encountered and often leads to poor asthma control. Therefore, it is vital to check for compliance and technique, and provide education as well as counselling to these patients.(7,8,13)

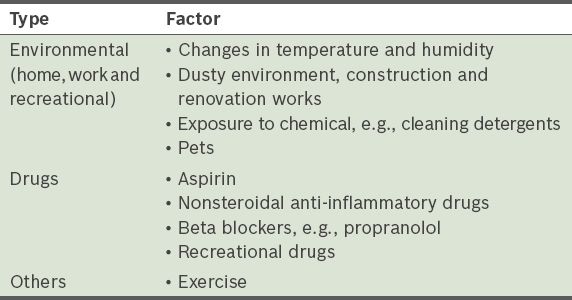

External factors

Detailed history-taking of the patient’s home and working environments and hobbies should be done to identify any potential exacerbating triggers of asthma (

Table III

Exacerbating triggers of asthma.

OPTIMISATION OF THERAPY

The pharmacological treatment of asthma relies on the use of ICS, inhaled bronchodilators and other controllers.(4)

A stepwise increase in the dose of ICS, in combination with an inhaled LABA, is commonly employed to achieve better asthma control. The addition of other controller medications, such as leukotriene modifiers and theophylline, can be considered.(14,15) It is important to take note of what constitutes high-dose ICS therapy. Examples of high doses of various ICS include beclomethasone dipropionate > 2000 DPI or CFC-metered-dose inhaler (MDI), budesonide > 1600 MDI or DPI, ciclesonide > 320 HFA-MDI, fluticasone propionate > 1000 HFA-MDI or DPI, mometasone furoate > 800 DPI and triamcinolone acetonide > 2000.

If the goals of asthma management are not achieved with the use of combined high-dose ICS and LABA after 3–6 months despite the use of the ‘ACE’ approach, a referral to a pulmonologist is warranted. The use of inhaled long-acting anticholinergic therapy (tiotropium),(16) oral corticosteroid or anti-immunoglobulin E therapy may be employed in selected patients.

WHEN SHOULD I REFER TO A SPECIALIST?

Referrals should be considered in the following circumstances:

If there is uncertainty in the diagnosis of asthma, especially in patients with inconsistencies between history, examination findings and spirometry results (e.g. atypical presentation or suggestion of an alternative diagnosis). If there are problems encountered in the management of comorbidities or alternative diagnosis. In ‘severe refractory’ asthma patients. In occupational asthma patients. On further enquiry, you discovered that Mr Tan had family and personal histories of atopy. He was a non-smoker and was compliant to his asthma treatment. He claimed to suffer from a cold, characterised as facial pressure and intermittent blocked nose over the past year. His inhaler technique was also noted to be suboptimal but improved with counselling. His symptoms of rhinitis improved with intranasal steroids. Four months later, his asthma symptoms improved significantly.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

Asthma is a reversible chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that can be effectively controlled without resulting in any lifestyle limitation or burden on the patient’s quality of life.

Management of a ‘problematic’ asthma patient starts with the ‘ACE’ approach. Any asthma patient with poorly controlled symptoms should have their diagnosis, risk factors and comorbidities, compliance and environmental triggers re-evaluated.

Identifying and addressing factors that contribute to ‘difficult’ asthma can lead to better asthma control.