Abstract

Constipation is common in infants and children. Helping parents understand the vicious cycle of childhood chronic constipation is the key to successful management. Weaning, toilet training, transitions to kindergarten/school, a bout of febrile illness and overseas holidays are common life milestones that may be associated with an increased risk of constipation. A detailed history and targeted physical examination can rule out most organic causes of chronic constipation. Infrequent defecation (≤ 2 per week), faecal incontinence, retentive posturing, painful or hard bowel movements or large diameter of stool suggest functional constipation. The Bristol stool chart is a free, useful tool for parents or caregivers to report and monitor the child’s stools. Red flags in constipation include delayed passage of meconium beyond 48 hours of life, associated intestinal obstruction symptoms, developmental delays, behavioural problems and frequent soiling of underwear. Behavioural modifications should be considered in primary care, together with pharmacotherapy such as laxatives.

Roy, a four-year-old boy, was brought to your clinic by his mother for a consultation, as she was concerned that he was constipated. Roy had only passed stool once during their family holiday in the preceding week. The stool was hard and pellet-like. On questioning their domestic helper, the mother was told that this had been his regular pattern for the last 11 months since Roy had started attending a playgroup.

WHAT IS CONSTIPATION?

Most physicians have no difficulty diagnosing and treating constipation. However, there may be slight differences in their definition of constipation. A useful working definition of constipation is a frequency of defecation of ≤ 2 times a week, and a stool consistency that is hard, dry and pellet-like or with cracks in the surface. The diagnostic criteria (i.e. Rome criteria) for functional gastrointestinal conditions, including constipation, have been developed and refined over the years. The most recent update, the Rome IV criteria, was published in 2016.(1)

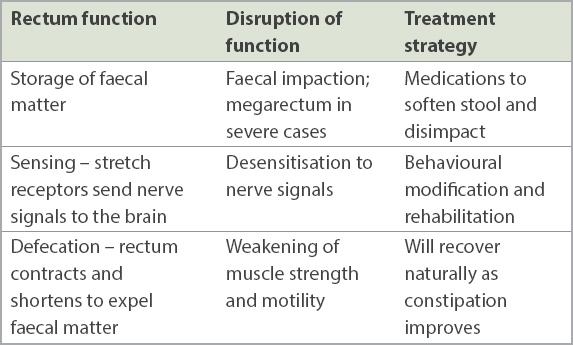

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria requires ≥ 2 of the following, occurring at least once a week for a minimum of one month: ≤ 2 defecations per week; ≥ 1 episode of faecal incontinence a week; retentive posturing; painful or hard bowel movements; large faecal mass in the rectum; and/or large-diameter stools that can obstruct the toilet. However, infrequent stooling in a thriving, fully breastfed baby is not considered constipation and requires only reassurance. A brief summary of rectal physiology is shown in

Table I

Summary of rectal physiology.

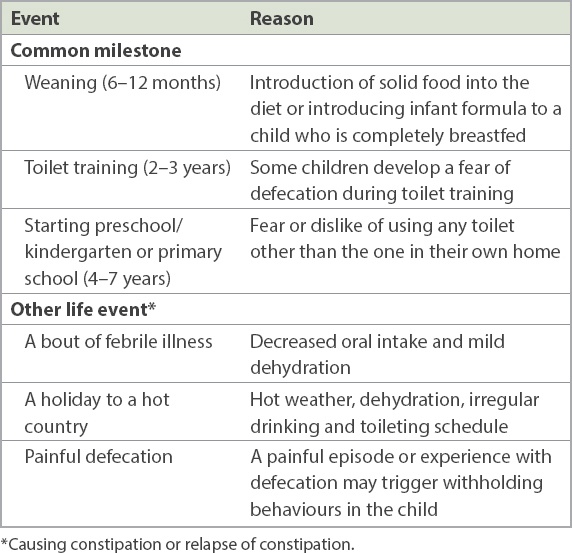

Table II

Common childhood milestones and life events associated with an increased risk of constipation.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

Constipation in children is very common, with a reported frequency of up to 30%.(2) The vast majority (96%) of cases are due to functional causes.(3) Organic causes of constipation are uncommon and most can be ruled out clinically. They include the following: Hirschsprung disease, hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, spina bifida/spina bifida occulta and medications that slow down intestinal motility.

Red flags for referral to a paediatrician are: delayed passage of meconium beyond 48 hours of life and vomiting with abdominal distension; young age of < 6 months; developmental delay or behavioural problems; failure to thrive; failure to respond to standard treatment; and frequent encopresis. Physical examination findings that require referral to a paediatrician are: significant abdominal distension, abnormal position of the anus and suspicion of spina bifida (e.g. absent lower limb reflexes, palpable bladder, absent anal reflex, tuft of hair on the spine or deep sacral dimple).

Beneath the surface, chronic constipation in children is actually a complex condition, contrary to what one might think. Biological, psychological and social factors interact in the ever-changing context of a developing child. This is not to say that all children with chronic constipation need to be managed by a paediatrician or psychologist. When more primary care physicians realise that chronic constipation is a genuine medical problem, parents will also come to the same conclusion and both will be better able and motivated to help the child.

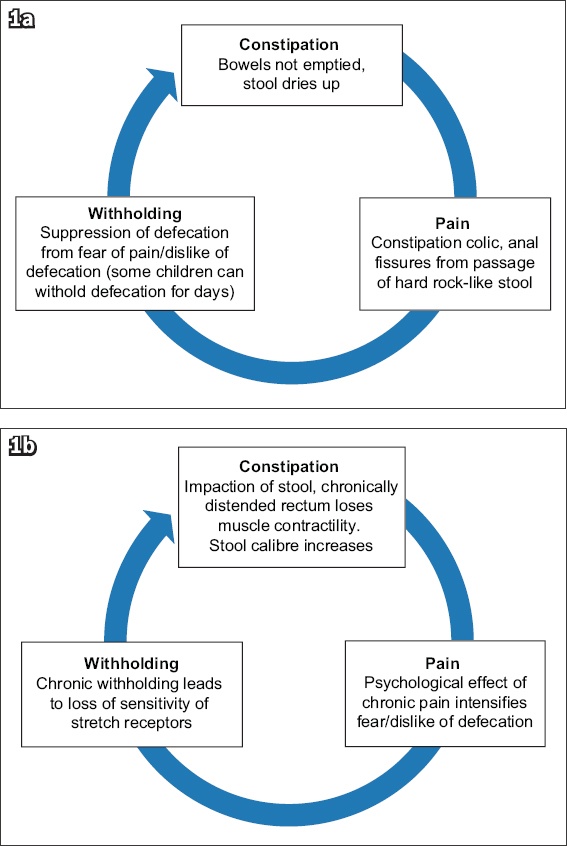

Most children with chronic constipation are caught in a vicious cycle (

Fig. 1

Charts show the (a) initial phase and (b) chronic phase of the vicious cycle. In constipation colic, the pain is commonly brought on by eating, because food stimulates peristalsis via the physiological gastrocolic reflex. Constipation colic also commonly occurs in the morning, because the urge to defecate is suppressed during sleep but activates upon waking. The pain is usually short-lived (once the peristaltic wave has passed), and many parents report that the child is well for the rest of the day, to their consternation.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

In a busy primary care clinic, it is common practice to prescribe laxatives for single-episode constipation with a clear trigger event. However, chronic constipation requires more of the physician’s time to diagnose and treat successfully.

Obtain history of previous treatment and relapse

Often, the child has already received some treatment and may have experienced treatment failure and relapse. It is important to explore reasons for the previous treatment failure. The physician should ask what medications were given (stimulant or osmotic laxatives; rectal suppositories or enemas), how they were taken (dose, frequency, duration and compliance) and whether there was any attempt at behavioural modification.

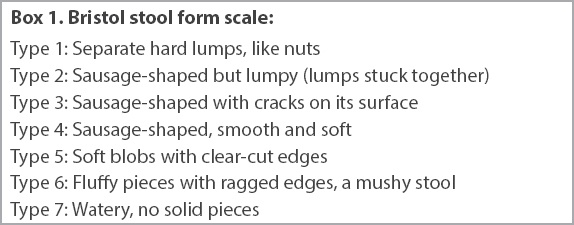

Bristol stool form chart: a free, useful tool

The Bristol stool form chart(5) (

Box 1

Bristol stool form scale:

Identify the correct caregiver

In many local families, both parents work full-time and children are cared for by childcare centres, domestic helpers or grandparents. Note that infant care centres (for < 18 months) in Singapore chart a baby’s feeding, urine and bowel motion daily, but childcare (for ≥ 18 months) teachers do not log these events. It is usually the parent who takes the child to see a doctor rather than the domestic helper or grandparents, and the parent may not know about the child’s bowel habits. Common responses from parents are: “I don’t know, I think he passes motion every day” or “the childcare teacher didn’t mention that he’s constipated” or the most unhelpful “you ask my child”. Hence, the Bristol stool form chart may be useless at the first visit. A reported history of Bristol Type 4 stools does not rule out constipation if that was observed only once; the child may be constipated the rest of the time. Thus, it is good to establish an understanding of the child’s social environment early in the consultation. Sometimes obtaining a collaborative history over the phone with the main caregiver is useful or even necessary. Conversely, sometimes the caregiver brings the child without the parent, who is the decision-maker, necessitating a phone discussion of treatment options with the parent. Each child has a unique context and environment, and the best therapeutic solutions are co-created with the caregiver or family.

WHAT ARE THE EXAMINATION FINDINGS IN CONSTIPATION?

Palpable faecal masses

Palpable faecal masses are common and can be easily felt in young children, who have a thin abdominal wall. They are best felt by positioning the child in the supine position, placing the examining hand over the left iliac fossa and ‘rolling’ the mass underneath the examining hand. They are characteristically indentable and are mobile, being located in the mobile sigmoid colon. Palpable faecal masses indicate a moderate degree of constipation; however, their absence does not rule out constipation.

Perianal examination

The perianal region should be examined for any anal fissures and skin tags, abnormal position of the anus, anal fistulas, anal stenosis, and an absence of anal reflex. It is best examined with the child in the left lateral position with hips and knees flexed, and the parent should be present to help keep the child calm. Digital rectal examinations are psychologically traumatising to children and may cause physical trauma in younger children if improperly performed. In the setting of a suggestive history, a per-rectal examination is not necessary for the diagnosis of constipation.

WHAT ARE THE COMMON PITFALLS?

Constipation cannot be ruled out just because the child passes stool daily. The child may appear to have regular bowel movements because of (a) false reporting by the child, (b) spurious diarrhoea, or (c) incomplete evacuation. Incomplete evacuation is usually functional because the child wants to quickly return to playing.

Moreover, laxatives do not solve the problem on their own. As detailed in this article, behavioural modification, with the support of osmotic laxatives, is the cornerstone of successful management of chronic constipation.

Oversuspecting Hirschsprung disease is another possible pitfall for the physician. Classical Hirschsprung disease is uncommon (one in 10,000 live births)(6) and is usually diagnosed in neonates or infants presenting with infrequent stooling, vomiting, severe abdominal distension or sepsis. Ultra-short segment Hirschsprung disease is rare, and its diagnostic criteria is controversial. While it is important to ask for a history of delayed passage of meconium, the physician should not make a diagnosis of ultra-short segment Hirschsprung disease in the absence of vomiting or abdominal distension. Passage of large-calibre, impacted stool is unusual in true Hirschsprung disease. Additionally, many mothers cannot recall if their child passed meconium on the first day of life; this does not mean that the child has Hirschsprung disease. Locally, the majority of babies are born in a maternity hospital and local nurses are well-trained to observe for delayed passage of meconium.

Lastly, investigations are not necessary to diagnose the majority of constipation cases. A supportive history and examination are sufficient.

HOW DO I MANAGE CHRONIC CONSTIPATION?

For chronic constipation, the overarching principle of management is educating the parents about the vicious cycle of constipation and how to break it. For a young child, one of the main issues contributing to ongoing constipation is withholding behaviours as a result of pain, fear or anxiety associated with defecation. Psychologically speaking, children naturally avoid painful or unpleasant tasks. Young children cannot be expected to reason out the importance of passing stool regularly to avoid the stool becoming drier and harder. Parents and caregivers need to work on ensuring that the passage of stool is less unpleasant and pain-free for the child. With time, the child will come to realise and understand that defecation is not as unpleasant an activity as they believe and be willing to do so more readily.

The two pillars in the management of chronic constipation are behavioural modification and medications. Many physicians only prescribe medications and do not talk about the former, leading parents to erroneously assume that medications will magically change the child’s behaviour. However, behavioural modification is the only way to achieve lasting treatment success.

Management pillar 1: behavioural modification

Behavioural modification targets the ‘constipation’ and ‘withholding’ parts of the vicious cycle.

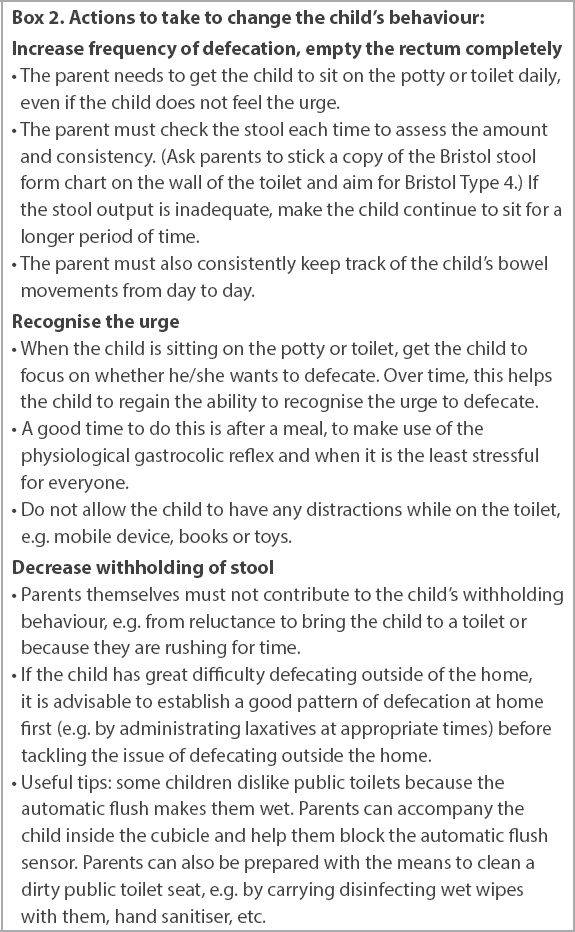

Box 2

Actions to take to change the child’s behaviour:

While these three steps may sound simple, the difficulty lies in getting the parents or caregivers to perform them daily. Managing chronic constipation requires commitment and consistency on the part of the parents or caregivers. While some of the tasks of parenting can be outsourced, for example, to a domestic helper, grandparent or childcare teacher, the responsibility for the child’s health still falls on the parents, and they should be the ones to coordinate the care of the child and ensure that any actions taken for behavioural modification are consistent among caregivers.

Other useful home tips include: (a) using foot support with a plastic stool or commercial toilet seat (

Fig. 2

Photograph shows a child toilet seat with foot support.

Management pillar 2: medications

Medications can be used to break the ‘constipation’ and ‘pain’ parts of the vicious cycle, in conjunction with behavioural modification. Although medications alone cannot effect lasting treatment success, they are important to ensure that the stools are soft enough to be passed painlessly.

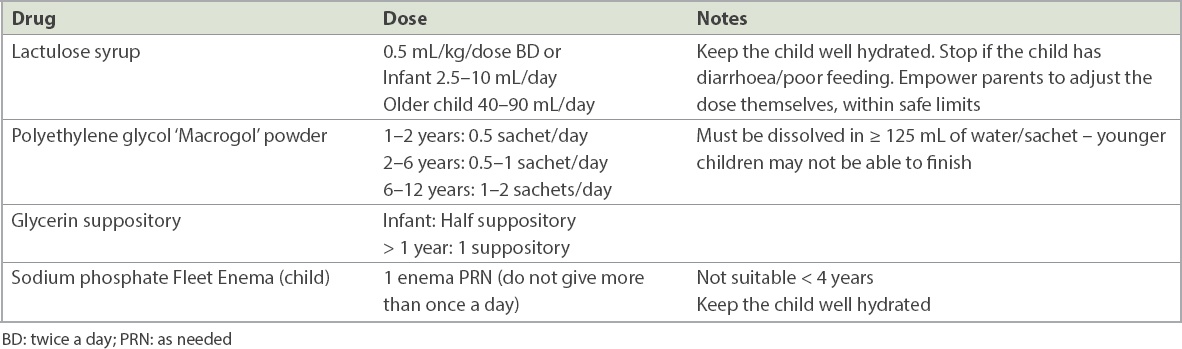

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives (e.g. lactulose, polyethylene glycol) are preferred over stimulant laxatives (e.g. senna, bisacodyl) as (a) osmotic laxatives are well tolerated over long periods; (b) many stimulant laxatives are not licensed for use in young children; and (c) with dependence on stimulant laxatives, behavioural modification and long-term treatment success cannot be achieved.

Osmotic laxatives soften stools and help them to be passed out smoothly. They do not work instantly, as the medicine requires time to travel the entire gut before reaching the distal colorectum, and the dose needs to be built up over a few days. Laxatives need to be given daily until the child has a daily soft stool (Bristol Type 4) and has overcome the fear of defecation. At this point, laxatives can be weaned off gradually, such as by decreasing the dose or by taking the medicine every other day.

Physicians frequently prescribe osmotic laxatives in the following ways: (a) on an as-needed basis only; (b) a short course; or (c) underdose due to fear of causing diarrhoea. Unfortunately, constipation will recur, as the vicious cycle is not broken. The duration of laxatives needed to break the vicious cycle is at least a couple of weeks or even months, not days, and should be proportionate to the chronicity of the constipation, as the rectum needs time to regain its normal size and contractility.

Table III

Recommended medications and dosages.

Common parental misconceptions and fears about laxatives

Misconceptions about laxatives need to be corrected by educating and reassuring the parents; otherwise, these mistaken beliefs will contribute to non-compliance. Common myths are that laxatives (a) are dangerous; (b) cannot be taken daily for long periods; (c) lead to dependence; and (d) are not effective.

It must be noted that not all laxatives are the same. Osmotic laxatives are safe and do not cause dependence; parents who voice this concern are likely referring to stimulant laxatives. They are not absorbed, and the side effects are minor (except diarrhoea). They can and should be taken daily for the treatment of chronic constipation. If the laxatives do not seem to be working, it is likely because of underdosage, faecal impaction or the wrong expectation that just one dose should work and have immediate results.

Cost considerations

As constipation is a chronic condition requiring medium- to long-term usage of medications, it is important to keep health affordable for patients. When selecting osmotic laxatives, keep in mind that the higher cost of medication would contribute to non-compliance and failure to break the vicious cycle. Cheaper medications such as lactulose are not necessarily inferior in efficacy.

Other medications

Topical lignocaine should be used for pain relief from anal fissures. Avoid steroid-containing creams (e.g. Proctosedyl) as these may cause thinning and discolouration of the perianal skin after prolonged usage.

Suppositories and enemas should only be used when there is severe stool impaction with or without severe abdominal pain. Locally, many parents are fearful of using oral laxatives and resort to using enemas (obtained over the counter) to make the child defecate, using them every time there is a ‘crisis’ of painful stool impaction, which may be as often as every few days. However, this method is only a stopgap measure; physicians must correct this practice by educating parents about the vicious cycle. As most parents experience, administration of rectal medications is highly unpleasant and difficult in a screaming child who is already having abdominal pain. Also, the intense abdominal cramps that follow only further entrench the child’s dislike and fear of defecation, intensifying the overall negative psychological experience of defecation. Laxatives and behavioural modification are the preferred choice of therapy, with enema usage kept to a minimum as far as possible. The goal is to make defecation as natural and ‘pleasant’ as possible.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Constipation is common in infants and children. Helping parents understand the vicious cycle of childhood chronic constipation is the key to successful management.

-

Weaning, toilet training, transitions to kindergarten/school, a bout of febrile illness and overseas holidays are common life milestones that may be associated with an increased risk of developing constipation.

-

A detailed history and targeted physical examination can rule out most organic causes of chronic constipation. Infrequent defecation (≤ 2 per week), faecal incontinence, retentive posturing, painful or hard bowel movements, or large stool diameter suggest functional constipation.

-

The Bristol stool form chart is a free and useful tool for parents or caregivers to report and monitor the type of stools observed.

-

Red flags in constipation include delayed passage of meconium beyond 48 hours of life, associated intestinal obstruction symptoms, developmental delays, behavioural problems and frequent soiling of underwear.

-

Behavioural modifications should be considered together with pharmacotherapy (e.g. laxatives).

-

Simple tips can be shared with parents, such as not having any distractions while on the toilet seat, foot support for young children when on the toilet seat, and capitalising on the gastrocolic reflex when timing for defecation.

-

Common pharmacology management includes osmotic laxatives or stimulant laxatives for older children, while topical lignocaine can be considered for pain relief. Steroid-containing topicals such as Proctosedyl cream should be used with caution to avoid side effects from prolonged use.

Roy returned for his review four months later. After taking lactulose for two months, he managed to defecate daily and his mother gradually weaned him off lactulose. He had established a routine of defecating after lunch at his playgroup and no longer asked for the iPad or threw a tantrum when taken to the toilet seat.

SMJ-61-68.pdf